Frank Stella is something of a downtown Manhattan institution. The celebrated painter and sculptor has lived in the same Greenwich Village house for nearly 50 years, and for almost three decades, until 2005, he worked out of an East 13th Street building—a former horse auction market—that has since been landmarked. But while the 79-year-old Stella has developed deep roots in the neighborhood, his latest collaboration—a career-spanning exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art—has landed him in league with the area’s most buzzed-about newcomer.

“Frank Stella: A Retrospective” is a roughly chronological one-man show that occupies the fifth floor of the Renzo Piano–designed Whitney, which relocated with great fanfare to the Meatpacking District this past spring. Stella has previously been the subject of retrospectives at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, so it made sense that when the Whitney planned the first exhibitions in its new building, the institution chose him.

“Gobba, zoppa e collotorto” (1985)

Open since October 30, the survey traces Stella’s remarkable career over the course of almost 60 years. Figuring out how to accommodate such a range of artistic output was no simple task. “Frank’s body of work is enormous, so narrowing the show down to a manageable size has not been easy,” says Michael Auping of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, who curated the show. “Making a checklist with a living artist is like a chess match.”

Talk to Stella about the process, and what he stresses is that he is indeed a living artist. “They’re trying to pretend that I’m dead,” he says one afternoon in a gallery space not far from the museum, regarding the push and pull between an artist and a curator over what work is important. Stella and Auping have struggled over the inclusion in the retrospective of the “Black Paintings,” a series made up of seemingly simple black stripes. “The ‘Black Paintings’ are absolutely critical to the retrospective,” insists Auping. “They’re the holy grail of Minimalism and the lens through which many of us view painting today.”

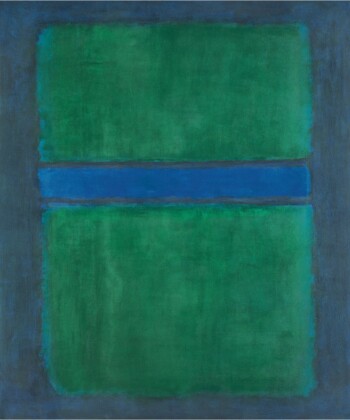

“Chocorua IV” (1966)

Stella, who created them in the late 1950s when he was making his living as a housepainter and found black enamel to be easily affordable, disagrees. “It’s true there is a kind of myth behind the ‘Black Paintings,’ ” Stella says, “or a reputation anyway.” But the artist rejects the notion that the works are of a piece. “The most telling thing about [the paintings] is that they are very different from one to another,” he insists emphatically. “Although black is the dominant color, they don’t look so much alike when you experience them in person.” Still, of the two dozen or so canvases, six of them ended up in the show.

And while Stella might not be thrilled with that chapter of his story—“He moved on a long time ago,” says Auping—there is plenty else for him to be excited about. Works on display include Das Erdbeben in Chili [N#3] (The Earthquake in Chile), 1999, a monumental two-dimensional piece featuring intricate illusions, as well as selections from his “Scarlatti K” series (2006–12), which boast twisted color planes and steel lines.

“Eskimo Curlew” (1976)

The assemblage of so much of Stella’s output is something of an event among art-world cognoscenti. “It is important for people to become familiar with all his series, to see how his work has evolved in a strategically built-up way,” says Agnes Gund, a longtime friend of Stella’s and collector of his work. “Frank is one of the artists you learn from. He’s had a great deal of influence on the history of art.”

That’s true not only of his early paintings and prints, but also of later work for which Stella was an early adopter of digital prototyping. The process allowed him to fabricate 3-D models and create the one-off parts he used for celebrated sculpture series in the late 1980s. And Stella hasn’t slowed down since. Despite hip and knee replacements, he still produces between 20 and 30 pieces annually, and says his work remains as creatively demanding as ever before. “I like painting and art-making activities to be physical,” he explains. “There’s no question that the degree of physicality I can put into it now is limiting, but I still go with it.”