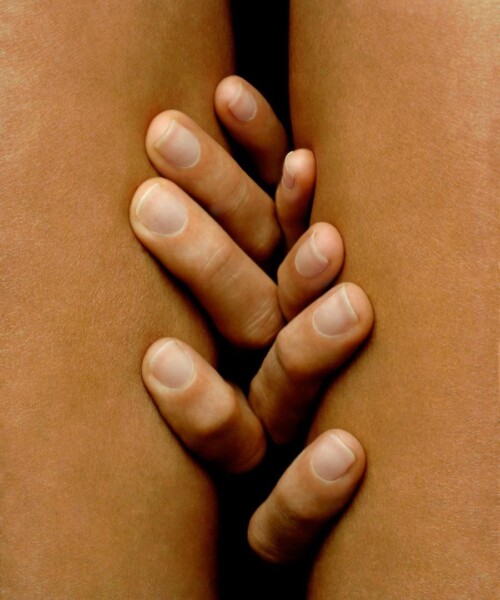

The thigh gap, in case you haven’t heard, is exceedingly trendy. Vice magazine called the gap—that airy divide between a thin person’s upper thighs—”the most desirable fashion accessory” and “the new cleavage.” Model Cara Delevingne’s perfect concavity has inspired @CarasThighGap, which tweets about craving peanut butter and working out daily “to stay this perfect.” Even the relatively highbrow online magazine Slate has wondered, “Do you have thigh gap?”

I don’t; not even close. Even at my thinnest—like that month in college I probably had Epstein-Barr—my upper thighs have remained persistently chummy, the bane of every single pair of expensive jeans I’ve ever owned. But a growing menu of noninvasive fat-reduction treatments promises to get rid of such stubborn areas with no surgery, no downtime and (mostly) no side effects. Which means a thigh gap, for me, may no longer be so impossible a dream. Hooray?

“In the last few years, body-sculpting technology has made vast improvements,” says Boston dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Dover. It’s most effective, he adds, for people who are at, or close to, their ideal weight, but who have localized pockets of fat they can’t seem to ditch. “The best candidates have concentrated areas of soft or jiggly fat—firm fat is way less responsive,” says Dover, meaning that spots like muffin tops and inner thighs tend to respond better than larger, firmer areas like the outer thighs and rear end.

To be clear: I’m not interested in looking like a waif, even if that were physically possible, but it’d be nice to own a pair of jeans for longer than six months. And so I opt for CoolSculpting, the most popular of the treatments on offer. How it works: A vacuum-like device suctions the target area and freezes the fat beneath the skin. The crystallized fat cells are gradually broken down, releasing their lipids, which are then eliminated via the body’s lymphatic system. (Other cells remain unharmed, Dover says, because fat is far more cold-sensitive than the skin itself.) Though the FDA has cleared CoolSculpting for use on belly fat and love handles, doctors have recently begun using the device on areas such as the upper arms, bra line and thighs. And research shows it actually works: In one clinical trial, patients saw their fat layer decrease by an average of 22 percent within four months.

At Dover’s office, I assume the birthing position as a tech attaches two suction devices to my inner thighs. During the hour-long session, my legs feel as if they’re being iced, but there’s no pain. There is, however, some initial post-treatment redness, and in the two weeks that follow, my thighs experience sensations that range from mild tingling and numbness to massive chafing. Dover says this is normal, and “nothing to worry about!” Though, yes, it sounds pretty serious. Full results can take up to six months to appear, but two months in, I’ve already lost a quarter inch on each thigh. My jeans still rub, if a little more quietly.

At the Upper East Side office of Manhattan dermatologist Dr. Neil Sadick, meanwhile, my editor tries out Liposonix, which uses focused ultrasound—a more intense version of the technology used in diagnostic imaging—to heat and destroy fat cells, which are, again, processed and expelled. Results can be seen more quickly, but in return, the procedure is more aggressive (and pricier: an average of $2,500 per session versus CoolSculpting’s $1,000–$1,500; Sadick offers both). For treatment of her below-the-rear area, Nicole is given two Percocet and a warning that the next hour will be no day at the spa, and it’s not, with some stubborn post-treatment bruising. (“Legs are purple,” she reports.) But eight weeks later, she’s lost an inch and a half on each leg.

So the question is: How much are you willing to endure, and pay, for an inch less of fat? Dover notes that, while safe, Liposonix is “poorly tolerated” by some patients. And Miami vascular and interventional radiologist Dr. Adam Gropper cautions that any procedure carries some risk. For instance, ultrasound-based treatments have the potential to destroy small arteries, veins and nerves and cause pockets of fluid called seromas to form under the skin. These seromas—which in some cases may even become infected—can require additional procedures to correct. “This is rare in well-trained hands, but many performing these procedures are not very experienced,” says Gropper. “A thorough inquiry into the level of experience and training of the physician should be made beforehand.” But probably the most common “complication,” he points out, is that of unrealistic expectations. “Many patients don’t understand the limits of what these procedures can accomplish,” he says. “These ‘sculpting procedures’ are just that: contouring for patients who are at or near their ideal weight, not weight-loss or fat-reduction procedures like liposuction or bariatric surgeries.”

Even so, doctors predict that within the next few years, body sculpting will catch up to Botox and fillers as one of the most popular cosmetic treatments among both men and women. (As Dover says, “Botox was the same. Early adopters were shunned by friends who couldn’t believe anyone would inject poison into their faces.”) At the very least, the options available, considerably cheaper and less intense than surgery, if also less effective, open up the possibility of thinner thighs to a much, well, wider audience.