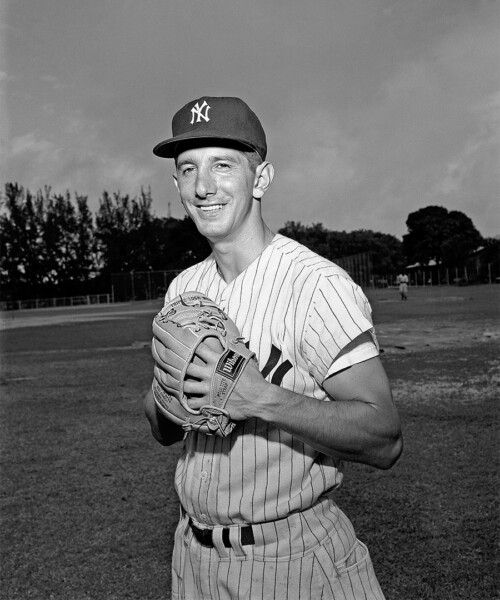

Billy Martin is one of baseball’s most famous figures, a “big city, bright lights manager” praised for his ability to turn failing teams into World Series champions but vilified for his temper as he threw dirt at umpires and screamed at both players and team owners. Howard Cosell once said: “Some love him, some despise him. But he’s the best. Maybe ever.”

Born into “a broken home surrounded by a shantytown” in Northern California, Martin was a professional baseball player and then a team manager, but his most famous job was “five loud stints as a central character in George Steinbrenner’s 1970s and 1980s mix of follies and championships.” Twenty-five years after Martin’s death in a car accident, award-winning sportswriter Bill Pennington decided to write about the manager “because I saw the fascination in people’s eyes when I told stories about him….Billy was beloved because he represented a traditional American dream: freedom. He lived independent from the rules. He bucked the system.” In this excerpt, Pennington describes the dawn of Martin’s epic career with the Yankees.

By the middle of 1975, Billy Martin had already resurrected downtrodden major league baseball teams in Minnesota, Detroit and Texas. He was widely viewed as a miracle worker and dugout genius, and yet each team he revived ultimately fired him for warring with management. Every dismissal devastated Martin, but losing the Texas job left him especially disconsolate.

Asked about his future in the Texas locker room, Billy wiped tears from his eyes and answered: “I have no idea. I love this game; baseball is my life. But at this very moment, I feel like telling the game to shove it.”

Billy escaped to the mountains of western Colorado, where he went fishing with his wife, Gretchen, and their son, Billy Joe. For days, the phone at their Texas home rang unanswered.

It was Gabe Paul, the general manager of the New York Yankees.

Martin, managing the Texas Rangers, arguing with an umpire

Paul was acting on orders from George Steinbrenner, the team’s owner of two years. Steinbrenner had been suspended from baseball after he pled guilty to making illegal contributions to Richard Nixon’s election campaign. Officially, Steinbrenner could not conduct Yankee business. But when it came to picking the manager, he was still unquestionably running the show.

The Yankees’ phone calls eventually made their way to Billy’s Colorado fishing lodge, but he refused to come to the phone. As Gretchen said nearly 40 years later, “He had built three winning teams and got fired three times. He was the reigning manager of the year and yet he still got fired. He just wanted to fish right then and that’s all.”

The Yankees were insistent.

At the Denver airport hotel where Billy finally agreed to a face-to-face meeting, contract negotiations moved quickly. At one juncture, there was a squabble over a behavioral clause—“a good boy clause,” as Billy’s legal advisor called it. George Steinbrenner got on the phone and said, “Let’s face it, Billy, this is the job you’ve always wanted. I’m giving it to you.”

It was not the last time that George would hold a carrot in front of Billy and demand that he take it.

On August 2, 12 days after he was fired by the Rangers, Billy Martin was named Yankees manager. In a press conference in New York, Billy, his face flushed and his voice cracking, said the day was a dream come true. “This was the only job I ever wanted,” he told reporters. Eighteen years earlier, Billy, then the Yankees second baseman and the inspirational leader of five World Series-winning teams, had been banished from New York baseball after one too many barroom brawls. Now in middle age, three years short of 50, he was back as the Yankees manager.

Billy had returned to Manhattan, but everything around him was different. In the mid-1970s, the Wall Street area was in decay, reflecting a faltering national economy. Times Square was no longer a place of panache and glitz but of peep shows, strip clubs and whorehouses. The city’s police force had been exposed as corrupt by former detective Frank Serpico. Strikes had damaged the public schools and services. Central Park rarely saw a pedestrian after 3 p.m.; people were afraid of being mugged.

That was the year New York officials turned to the federal government for help with a fiscal crisis. President Gerald Ford announced he would veto any bailout. As the headline in the New York Daily News said in huge bold type: “Ford to City: Drop Dead!”

Yankee Stadium, once a majestic symbol of the city itself, had been shuttered for renovations. That forced the Yankees to play the 1974 and 1975 seasons at Shea Stadium, squeezing in games whenever the Mets were on the road. Renting space from a fledgling baseball colleague was humiliating to the franchise of Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio and Mantle. The Yankees were dressing in another team’s locker room. And the ceiling leaked.

“I had heard so much growing up about the Yankees and New York and then I got there and it was like we were playing in some minor league place, like Toledo or something,” said Lou Piniella, who the Yankees traded for in 1974.

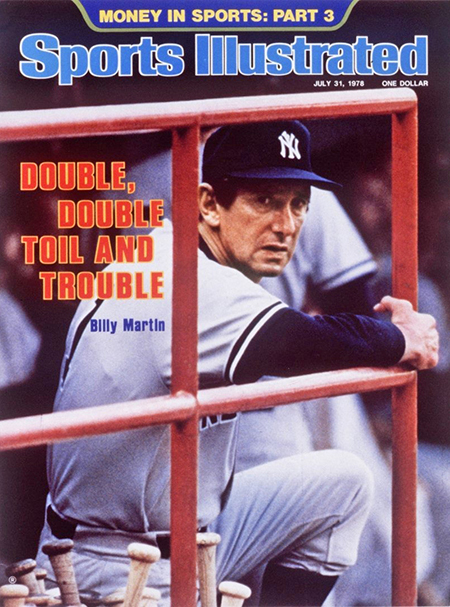

Martin on the Sports Illustrated cover, 1978

The Yankees that Billy inherited were not going to catch first-place Boston, a team thick with young talent. Billy’s goal was preparing for 1976. With Steinbrenner not allowed at the ballpark or the team offices, Billy developed a good working relationship with Gabe Paul. They agreed on a plan to completely remake the roster. The central goal was to give Billy some youth and quickness in the lineup.

“I remember leaving the clubhouse after our last game in 1975,” Piniella said. “I had an awful season and I was hurt. Billy was standing at the door and he says to me, ‘Lou, don’t worry about it. Go home and get healthy. We’re going to win the pennant next year.’

“He told the other guys that, too, and we believed him. And those who didn’t believe him, it’s like he knew who they were because by the time we got to spring training, they were off the team.”

Billy went to Florida early for spring training. He could not wait for the players to trickle in, to feel the presence of a team forming as a unit. Steinbrenner, who Billy did not know very well but of whom he was suspicious, was far away. His suspension from baseball was to extend until November 23.

Late in the previous season, Steinbrenner had taken to taping pep talks for his players on an audio cassette. Prohibited from going into the locker room, George ordered Gabe Paul to have the speeches played for the team before certain games as a way to motivate them.

The cassette player would be placed on a stool in the middle of the clubhouse with the volume turned high.

The first speech was just two minutes long. The next one a week later was a little longer. When the third speech went on for more than four minutes, Billy emerged from his office, stalked toward the middle of the clubhouse and kicked over the stool. Then he pushed the “stop” button on the cassette.

The players roared their approval.

NEXT: “Billy just kept everyone on edge.”