First it was the novels. Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, about the tumultuous career of Tudor power player Thomas Cromwell, each won a Booker Prize. Second came the theatrical adaptation, which was a tremendous success on the London stage. Third is the six-part television series, starring Mark Rylance and Damien Lewis, which premieres on PBS on Sunday, April 6th. Just three days later, Wolf Hall: Parts 1 & 2, opens at the Winter Garden Theater on Broadway. The two parts can be seen separately or in sequence, adding up to five and a half hours.

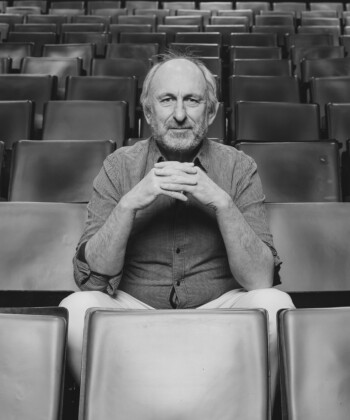

We asked Ben Miles, who played Thomas Cromwell in London and traveled with it to New York, why this Tudor-era drama fascinates audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

A newspaper columnist in England celebrated Wolf Hall, the play and the television series, as a return to political drama. Would you agree with that?

In part. It’s a play about political events, sure, but you really see the people who make those decisions and why they make them, the personal turmoil and the chaos that surrounds these monumental decisions that were made. The choices that people make in the play, the decisions they make, the corners that are turned, historically speaking had huge influence on the way we live now in the UK, and in Europe. And I think in the U.S. people will see parallels to today as well. It’s a great story of power and of personal ambition.

What is at the core of Wolf Hall?

These plays are about Thomas Cromwell trying to manage ones man’s will—that is to say, Henry VIII, trying to manage a very volatile, unpredictable and incredibly powerful individual and also to steer the individual in such a way will enable Cromwell to better himself, better his peers, better his family, better his beliefs, to radically change the way the country operated in that century.

I’d like to read a description of Cromwell in a letter written during his lifetime. It was written by the Imperial Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, who knew him well: “Cromwell’s words are very fair indeed, but his deeds are bad, and his will and intentions beyond comparison worse.”

That’s brilliant. I love that. He must have pissed Chapuys off that day.

Wolf Hall

It seems that Cromwell was a Machiavellian minister. What is it like to play someone that cunning?

Oh, it’s fun. I’m still inquiring as to his motives. I couldn’t give you a definitive answer as to why he does certain things. He is an enigma. Hilary has said he is a historian’s nightmare and a novelist’s dream. What she’s managed to do is to fill in the gaps in a very creative way. But he is essentially a survivor. He is a man who took great knocks as a youth and was born into an underprivileged section of society, disappeared into Europe and reinvented himself and then returned. He’s self-taught; he’s a self-made man. You could argue he’s kind of the American dream in a way. He pulled himself up by his bootstraps, educated himself. Gained skill and notoriety. If you wanted anything to be fixed, he knew how to do it. He knew how to talk to ambassadors, he knew how to talk to gunsmiths. He knew how to put the fright into someone in a back alley as well. He was the go-to guy.

I have a theory that Americans most like to watch British productions that are tackling the question of class. That’s really what Downton Abbey is about. And I’m not sure Wolf Hall would be as popular if its protagonist wasn’t from humble beginnings.

It wouldn’t be half as compelling. That’s one of the main threads of the story. A man from nowhere, this piece of dirt, is overtaking the most influential lords, the oldest aristocratic families in the land. He’s a working class hero.

Anne Boleyn is a woman who has obsessed people for five centuries. Cromwell brought her down. What do you believe in your heart he really thought about the queen?

It’s very complex. In part he admires her; they are similar people in that they are climbers. She’s a bit of an intruder and she’s certainly on the make when she comes from the French court back to England. She has her eye on the highest prize absolutely. He recognizes that in her, and at the same time she has religious ideas that are similar to his, so she is useful to Cromwell in many ways. But she becomes a liability once she gets that power, and Henry tires of her, and Cromwell’s main task is to get rid of her. At that point I think Cromwell puts his feelings for her aside, and he thinks of her in terms of how best can I bring about her downfall. He disregards the truth when it comes to her trial and the executions; he’s concerned with practicalities. He can have a heart of stone at times. You wouldn’t want to cross him.

I know you’ve acted in period drama before this and done quite a bit of theater. But have you ever performed on stage for such long periods?

No! It’s crazy. I’m on stage for three hours for each show. I think I have a scene and a half off for Wolf Hall and 30 seconds off for Bring Up the Bodies.

That’s incredible. How do you do it?

It’s a bit more like sport than art. I have to eat well and I work out and I try to be sensible. I do have to stay physically fit for this show. If you don’t, it can wear you down. But it’s such a great challenge and it’s invigorating, it really is. Enlivening.

My last question: Have you thought about what Thomas Cromwell would make of New York City?

He would have loved it; he would have been mayor in a month. It’s his kind of town.

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of a trilogy of Tudor mysteries published by Touchstone books. For more information, go to nancybilyeau.com

Photography by Johan Persson