When Deborah Harkness, a professor of European history at the University of Southern California, turned her knowledge of Renaissance magic, science and family life into a novel, it was an instant sensation. A Discovery of Witches hit the New York Times best seller list in 2011. Next came Shadow of Night, and last week Harkness’s final book in the trilogy, The Book of Life, was published by Viking and snapped up by her ravenous readers. The All Souls Trilogy, as it is called, fuses Harkness’s deep understanding of supernatural beliefs across millennia with a playful imagination and strong storytelling gifts. Her novels’ main characters are Diana Bishop, a scholarly witch, and Matthew Clairmont, a scientific vampire—and the couple is surrounded not only by fellow witches and vampires but by demons too. And oh yes, plain old human beings.

DuJour’s executive editor, Nancy Bilyeau, the author of a trilogy of historical novels set in the 16thcentury, sat down with Harkness to talk about history, storytelling and the supernatural.

The Book of Life

How did the idea come to you in the first place to write a novel about witches? Was it planned over time?

No, it was a complete and total accident. I had just finished a research project that took years and in the fall of 2008 I was on a family vacation, walking through an airport in Mexico City, and an entire bookstore was books about witches, werewolves, vampires, demons, shape-shifters, fairies, you name it—all of them next to Time magazine, Newsweek and Oprah. I stopped and thought, This is so bizarre. I had just researched subjects in the 16th century and this was what they wanted to read about too. My students don’t have much in common with a 16th-century person and yet their reading tastes are identical.

Of course! There was even a book written in the 1560s by a Dutch physician in which he listed all the names and titles of the demons and what they could do, what they were good at. It’s incredibly detailed.

That’s the world I research and teach, the one you’re talking about, where there was an absolute belief that these things were all around and you could and should know them, characterize them, recognize them, so if you met one in the market, you’d know it.

In the airport, you had the idea to put the spirit of five hundred years ago into a book set today?

I was in this hotel, it was raining a lot, soccer was on and not much else, and I kept thinking about it. Unlike the 16th century, our worldview doesn’t support the existence of these creatures in the same way. Then I thought, Ok, well then, how could a worldview today support it? I started with practical questions. If you were a demon, what would you be like? You wouldn’t have red eyes that glowed and be evil. If you were a witch, you might not want everyone on the block to know. And what if you’re a vampire? What would you do for a living and how would you date? It became a mental game of mine. I was playing with a little imaginary universe. And suddenly my imaginary friends are talking to each other, and I’m writing it down, and I thought, Oh, my God, I’m actually writing a novel.

I went to your reading in New York City of A Discovery of Witches, and I remember there were two women with questions who identified themselves as Wiccans. Do you get that a lot?

Yes, I was very conscious the whole time I was writing that there’s a religious base that traces its roots back through the history of witchcraft and what is important for them to realize—and for the readers to realize—is that my novels are not a depiction of modern Wicca. That would be a different book. Mine is an attempt to take what people thought about witches in the 16th century and bring it forward. By and large, the Wiccans have acknowledged that, and they like the fact that I haven’t mocked their religious faith.

Then there are the demons, and your depiction is very interesting. Quite different from what we see in films like Paranormal Activity. How do you feel about Hollywood’s view of demons?

Those filmmakers are following in the footsteps of Christian tradition about demons. Mine are much more ancient. In Greek and Roman tradition, everybody had a demon. Demons were like your guardian angel; they were spirits and guiding forces in your life. They helped you out and told you what to do, and it was positive.

When Christianity came into being, they pushed other belief systems out of the way. They didn’t want you to listen to a lot of voices; they wanted you to listen to God. So there was literally a demonization of demons. But the roots of genius lie in demons; they were spirits of inspiration and creativity. That’s one of the fun things about writing fiction, to go back and say, ‘Wait a moment, what if the Greeks and Romans were right and demons were pretty terrific?’

I love what you’re doing with the vampires in your novels: they are living in these fascinating, intricate families. All sorts of vampires.

I didn’t want my vampires to be similar and I didn’t want there to be a lot of ‘I hate being a vampire.’

Between Anne Rice and Stephenie Meyer—and even a bit with Charlaine Harris—we have so much of the reluctant vampire.

That is because we writers are playing with the ethics of life and death. Do you know, in a way, that’s a very modern preoccupation? Humanitarianism is an 18th-century idea; it doesn’t exist prior to that. Prior to the 18th century, there’s no sense that anyone has a right to life. That’s not to say people killed with wild abandon. It’s just that there’s a different sensibility: People presumed you were going to lead a short life and probably die horribly and then you were going to heaven, hopefully, where everything would be great. So the older your vampire is, the less likely it is that he or she would have that kind of humanitarian sensibility.

How do you feel about the way your books have been received as far as the genre they’re assigned to? That affects how they are reviewed and marketed and everything.

Being an academic, I didn’t know there was such a thing as genre. That sounds completely unbelievable, but honestly I thought there was fiction and there was nonfiction and I was pretty clear that I was moving into fiction. I had no idea there were so many rigidly enforced boundaries. ‘No, that’s urban fantasy, or no, that’s paranormal fiction or no, that’s historical thriller.’ People have said to me, ‘You don’t understand the genre you’re writing in.’ I said, ‘Wow, well guess what, I didn’t know I was writing in a genre, so I can’t follow rules I don’t know and never signed on for.’ I don’t think in buckets like that. Genre can be a wonderful room to play in or it can be a prison. I think all readers, irrespective of whether they’re reading nonfiction or fiction of any kind, want a good story.

And that is what you are giving them. Thank you.

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of The Crown and The Chalice, published by Touchstone Books. The Tapestry will be published in March 2015.

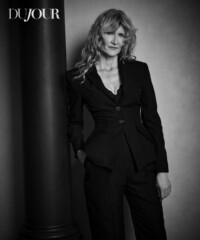

Photo by Scarlett Freund, 2014.

MORE:

4 Must-Read Page Turners Inspired by the Past

Summer’s Hottest Fiction Reads

3 Highbrow Writers Dive Into Genre Fiction