I loaded my snowboard and took the sixth seat inside the Telluride Gondola. “Raise your right hand and repeat after me,” a guide instructed my fellow passengers and me. “I solemnly swear never to tell anyone how good things are in Telluride. I promise, instead, to tell others the food is terrible, the skiing is terrible, and the people are mean.” Everybody laughed, but the directive hung in the air like a melting icicle. Little did he know this silent spectator was mulling over a narrative for her exposé on Colorado’s uncut gem.

In the West, Telluride is known as a bit of an outlier. It’s located in a narrow box canyon enclosed on three sides by the San Juan Mountains, a range in the Rocky Mountains of Southwestern Colorado. The place has always had a reputation for attracting rebels and pioneers: Its founders were silver and gold miners on a treasure quest. It’s where Butch Cassidy kicked off his bank-robbing career. It was home to the first long-range AC power plant—though not, contrary to legend, the first electric streetlights. But many fled after the silver bust at the end of the nineteenth century, more were drafted into WWI and never came home, and those who stayed began mining for coal and minerals, an industry that persevered until the late 1970s, when the last mine finally closed its doors.

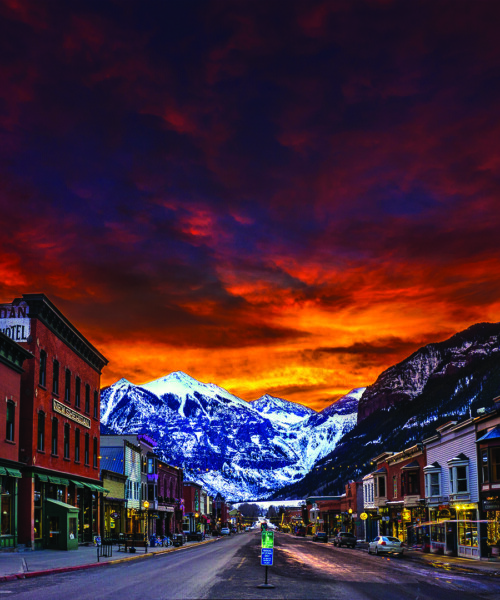

Telluride is small: everyone knows everyone. The entire town is a National Historic Landmark District, and little has changed aesthetically since its settlement. Colorado Avenue, its main thoroughfare, is 12 blocks of brick and wood buildings that include Victorian landmarks like the New Sheridan Hotel, the Last Dollar Saloon (aka “The Buck”), and the Nugget Theatre, which opened in 1935 and is home to the Telluride Film Festival. Following the Telluride Ski Co.’s 1972 transformation of the former mining area near Gold Hill into a recreation zone, the hippies who’d been squatting in its abandoned buildings began to mingle with miners and skiers. Together, they forged a laid-back culture that continues to define the current population, an equally diverse mix of artists, ranchers, CEOs, and celebrities like Ralph Lauren, Jerry Seinfeld, and Tom Cruise.

When I arrived at the Dunton Town House, a new luxury boutique hotel, three days of nonstop snow had blanketed the town in two feet of Colorado powder. People crunched along the sidewalks, but in such a skier’s paradise, snow is not an inconvenience—it’s the mother lode. Still, many people claim that Telluride’s summers, with idyllic weather and a different festival every weekend, are the closest thing to heaven. No matter one’s reason—or season—for coming, people don’t care much about how many acres you’re on or whether you drive a Range Rover. A thirty-something skier I met explains: “The rich go to other mountain towns to be seen. They come here not to.”

On my first night in town, I visit The New Sheridan’s saloon. It’s packed. Observing the crowd, I notice it’s mostly a sea of men. “No, there is no rosé served in the middle of January,” the bartender says to one of the few other women in sight. He isn’t rude, but he doesn’t seem too concerned about catering to a stranger’s demands. In a state where so many historic towns have rushed to attract tourists, Telluride locals seem determined to keep their home as it always has been—which makes it all the more attractive to the rest of us.

As enticing as its warmer weather and local charm may be, Telluride’s real thrills are on the hill. Tipping the scales at more than 2,000 acres, the main ski area is conveniently situated: it’s 13 minutes by gondola from the south side of town to Mountain Village, where a nest of more conventional ski resort establishments (a Fairmont, a Starbucks) have sprouted up. Lifts from Mountain Village access most of the trails, including the intermediate runs off of Prospect and Sunshine Express, as well as the stunning double-black steeps of Revelation Bowl and Palmyra Peak. The views from atop Telluride are some of the most beautiful in Colorado, surrounded by the largest concentration of 13- and 14,000-foot peaks in the country.

Riding up on the lift for a last time, I take in the breathtaking perfection. It’s a “Colorado Bluebird Sky” day, without a cloud in sight, and the sun is warm on my face. To my right, Wilson Peak—recognized by many as the iconic pinnacle that adorns Coors Light’s beer cans—sparkles under a fresh blanket of snow. It strikes me that millions of people have unknowingly glimpsed this natural wonder as they crack a brew—certainly an unmemorable moment. But watching it rise before my eyes is anything but forgettable. Right then I realize that maybe this is a secret worth holding after all. So let’s make the Telluride pact: We’ll keep this between you and me.