It’s not for nothing that Tulum has been called the Brooklyn of Mexico. You can hardly pose for a perfectly studied Instagram picture there without getting an Edison bulb, a hand-crocheted bikini and three flannel shirts in the frame. Add to that list a decent cocktail, because ever since bartender Jasper Soffer arrived on the scene there last year, those have been popping up all over town. This spring, Soffer even opened an outpost of Mulberry Project, the New York City cocktail bar he co-owns, at a hotel on Tulum’s main strip, serving bespoke drinks with all the rococo standbys—infused booze, custom bitters, fresh fruit—mere feet from a scene worthy of a Corona ad.

You can blame the Internet for this flattening of the international cocktail landscape. Take a trip around the world and you’ll find American libations everywhere: Classics like old-fashioneds and French 75s are easy to spot, but also keep an eye out for Earl Grey MarTEAnis, made with earl-grey-tea-infused gin, lemon and egg white, and Gin-Gin Mules—gin and ginger beer mixed with lime. Both were created by cocktail visionary Audrey Saunders at Manhattan’s Pegu Club sometime in the mid-aughts and have since globe-trotted farther than some Victoria’s Secret models.

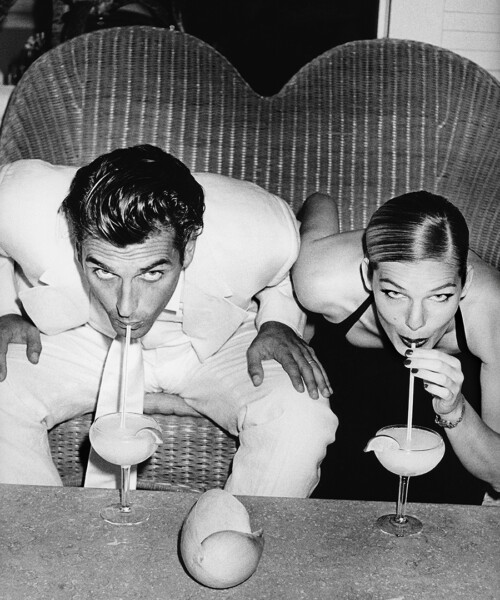

Another well-travelled drink is the Penicillin, a scotch, lemon, honey and ginger cocktail invented by bartender Sam Ross at New York City’s famed Milk and Honey. You can now order it from a wicker bench at Perch in L.A., at Silk & Grain in London, where the scotch is aged in leather, and at the subterranean Lockwood in Paris.

Some of this spread comes from the globalization of the restaurant industry. It’s not uncommon these days for hotels or parent companies to run outposts in multiple countries. You’ll recognize Los Angeles–based cocktail consultants Proprietors LLC by the opium-den vibe of their establishments in New York (Death and Co.), Los Angeles (The Walker Inn), Jackson Hole (The Rose) and Hong Kong (Lily and Bloom). Then there are cocktail consulting companies, like NYC-based Liquid Lab, which will create menus for new bars wholesale and even train the staff to make the drinks to the tune of thousands of dollars.

There are also more sinister methods of acquiring trendy drinks. “Let’s say you’re in Bolivia, or Montenegro,” says Soffer. “You decide you want to make a good cocktail, so you go online and look up what people are doing. Either you call the bartenders up and bring them in, or you pinch ideas from their menu and make them yourself.” Soffer brought his craft to nine countries (the U.S., England, Nicaragua, Mexico, Bolivia, France, Brazil, Australia and Peru) while on a three-year world tour, but anyone with a computer and access to Yelp could make knockoffs of his specialties.

As you might imagine, bringing bartenders in to pull a few shifts (known as “staging” in chef lingo) has more fans among the bartending community than pilfering recipes does. Modern bartenders, whose training can often be traced in family trees like that of chefs or samurai swordmakers, are often recruited for shifts in international bars in exchange for room and board, money and/or prestige. After meeting a Swede while bartending at Dutch Kills in Queens, New York, Jan Warren worked a mini-golf tournament in Germany and a party on Gotland, “the Martha’s Vineyard of Sweden.” He has since worked in six countries.

“I put on my résumé that I speak conversational Vietnamese, which has never really been helpful for a job before,” says Linda Nguyen, a Vietnamese-American bartender who works at Lock & Key in Los Angeles. “But when the owner was interviewing me, he said he was in the process of opening a bar in Vietnam. He asked me if I would be willing to work overseas.” Over about six months, Nguyen teamed up with the management of Lock & Key to bring the trend of communal punch bowls to a rooftop bar called Skylight in the resort town of Nha Trang. Since she’s been home, another bar in Nha Trang has already ripped off the trend—serving complex shared cocktails in large bowls.

Nguyen puts worldwide cocktail mimicry down to one simple fact: There are only a handful of drink prototypes to play with, and inventing something entirely new requires vision. “It’s very difficult to create a genuinely brand-new cocktail that is not similar to anything that’s ever come before it,” Nguyen says. Creating beverages at a high level is much like being a chef—trends and national traditions drive much of the innovation. Only occasionally does a person come along who truly turns the craft on its head.

The good news is that the march of classic cocktails around the globe may be speeding this process up. Adaptations, driven by creativity, necessity or both, are sometimes better than the originals. For example, it’s difficult to procure heavy cream in Nha Trang and there are no lemons, so Nguyen adapted a classic brunch drink from New Orleans, the Ramos Gin Fizz (traditionally gin, egg white, cream, lemon and lime juice and orange flower water), to be made with locally available passion fruit, mint and lime.

This is not to say that the United States has a monopoly on covetable cocktail trends. Any bar that’s offering gin and tonics with flourishes like rosemary or blueberries can credit northern Spain, where the craze of offering full “gin-tonic” menus has been flourishing for years. Bar Goto, a buzzy year-old New York City boîte from Japanese-American bartender Kenta Goto, uses ingredients like shiso and yuzu, as well as a milky Japanese soda called Calpico.

“The first time I guest-bartended in London, at a bar called Trailer Happiness, I felt like everything was really playful and whimsical, especially compared to the U.S., where we have gone in a kind of austere, pre-prohibition direction,” says Yael Vengroff, beverage director at The Spare Room in Los Angeles. “They had this kaffir-lime-infused Midori, a product that is frowned upon by bartenders here. But the combination was so delicious, I never forgot about it. And on the last menu I did for The Spare Room, I made a version of a Midori Sour with Midori, lime juice, muddled kaffir lime and Hendricks gin.”

In short, you can’t go anywhere without being everywhere. This is unequivocally great for bargoers, except that it does tend to dull the weird edges of bars you visit on vacation. These days, if you want to taste something unlike anything you’ve got at home, you might have to take a plane to a boat to a car to an elephant to an island with no Internet. Or maybe just order a beer.