For Lia Ices, making her third album was more than just collecting songs, it was a journey. As the Connecticut-born, New York-based musician began working on Ices, she was also beginning a move to California, a relocation that would heavily influence the songs she was writing.

The resulting album, out this week, is a gorgeous collection of electronica-tinged pop songs that feel at once familiar and totally new. Here, Ices talks with DuJour about long-distance relationships, learning to make beats and why hotels are the best recording studios of all.

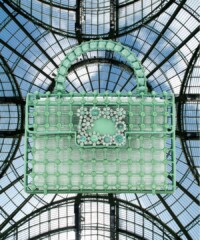

Ices

This record finds you working with your brother for the first time. How did that come about?

I’ve been by myself for all of my other records, but after [my second album] Grown Unknown, I was in a really good groove with my band—which includes my brother—and the songs kind of started to come naturally. Whereas the songs themselves on the record are very introverted, they became naturally bigger, louder and a better expression of what I wanted to do. So, I decided to move to the Hudson Valley with my brother and make an album with him instead of going away by myself to make one. We were just outside the town of Hudson; we lived on Roberta Flack’s farm with retired racehorses. There gets to be a point in any artist’s career when you need to go in and learn a new skill set, develop a new language, and make new work, so that’s what happened.

Roberta Flack has a farm that someone can just rent?

Yeah, we found it on Craigslist.

Crazy! So what sort of skills did you learn in this case?

I learned software, technology, programming, making beats and analog synthesis. Whereas my approach before was kind of a throwback with a super analog, 1970s-style singer/songwriter journal and a piano, I wanted to make beats and challenge the song writing process.

Which came first, the lyrics or the music?

This time the sounds came first. I came at it like a producer. When you really get into that world, it’s like an enabler for being even more creative, so it’s just like a ton of experimenting.

What effect did moving back and forth have on the process of making this record?

My boyfriend lived in Sonoma, so there were so many dichotomies. I’d be in a two or three week wormhole of intense music, then have to fly across the whole country and see him and explain what I was doing, listen to music and then be in this place that was really new to me. The way it looks, the openness and the people—it was just so different. It got me thinking about flight, freedom and how you can make life anyway you want it to be. You can make any type of music; it enabled this freeness. Being in a long distance relationship is kind of bizarre, but it worked for a bit, which felt kind of cool to me. It seeped into the creative process where you’re just like, ‘this works for me.’

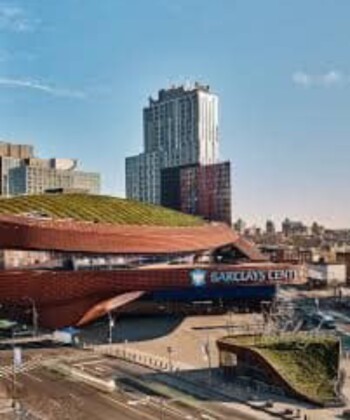

And it wasn’t just California and Hudson, didn’t you also record at Brooklyn’s super-popular Wythe Hotel?

We really wanted to work with Clams Casino, the hip-hop producer, so we sent him tracks and tried to work independently, but it was really hard to do while in different places. We decided to work together, but we didn’t want to be in a formal studio. I’m friends with the owner of the Wythe Hotel, Andrew Tarlow, and the rooms are amazing, just glass looking over the Manhattan skyline. We decided to rent one and bring our stuff down. That seemed to be the best place to work because it was so neutral; it wasn’t my space or his.

Can you see going back to making records the way you did before this one?

I feel like the project has recently found what it is, that’s part of why I named it Ices. I don’t think it will take me as long to put out an album the next time, because I found the sonic language that I want to play with for a while.

Are there any specific tracks that you think exemplify that?

“Love Ices Over” was a big one for me. You know, I love the blend of letting all your influences come in. With a song like that, there’s trapped beats, acoustic guitar and analog synthesizer; the vocals are processed in this way that reminds me of Sinead O’Connor. It’s like when I let everything I like about music come in, even just a little, it feels like a better expression of what I can do than if I shut the world out.

MORE:

Jesse Jo Stark is a Punk Revelation

On New Zealand Native Kimbra’s LA Farm

Jenny Lewis on Insomnia and Collaboration