It’s not often that a species on the brink of extinction gets a literal last-minute reprieve. A number of wildlife species have been able to skirt extinction and make a relatively healthy recovery, including the black-footed ferret, the golden lion tamarin, and the California condor. But over the summer, another critically endangered species unexpectedly joined the list of comeback kids: the Loa water frog in the Antofagasta region of Chile.

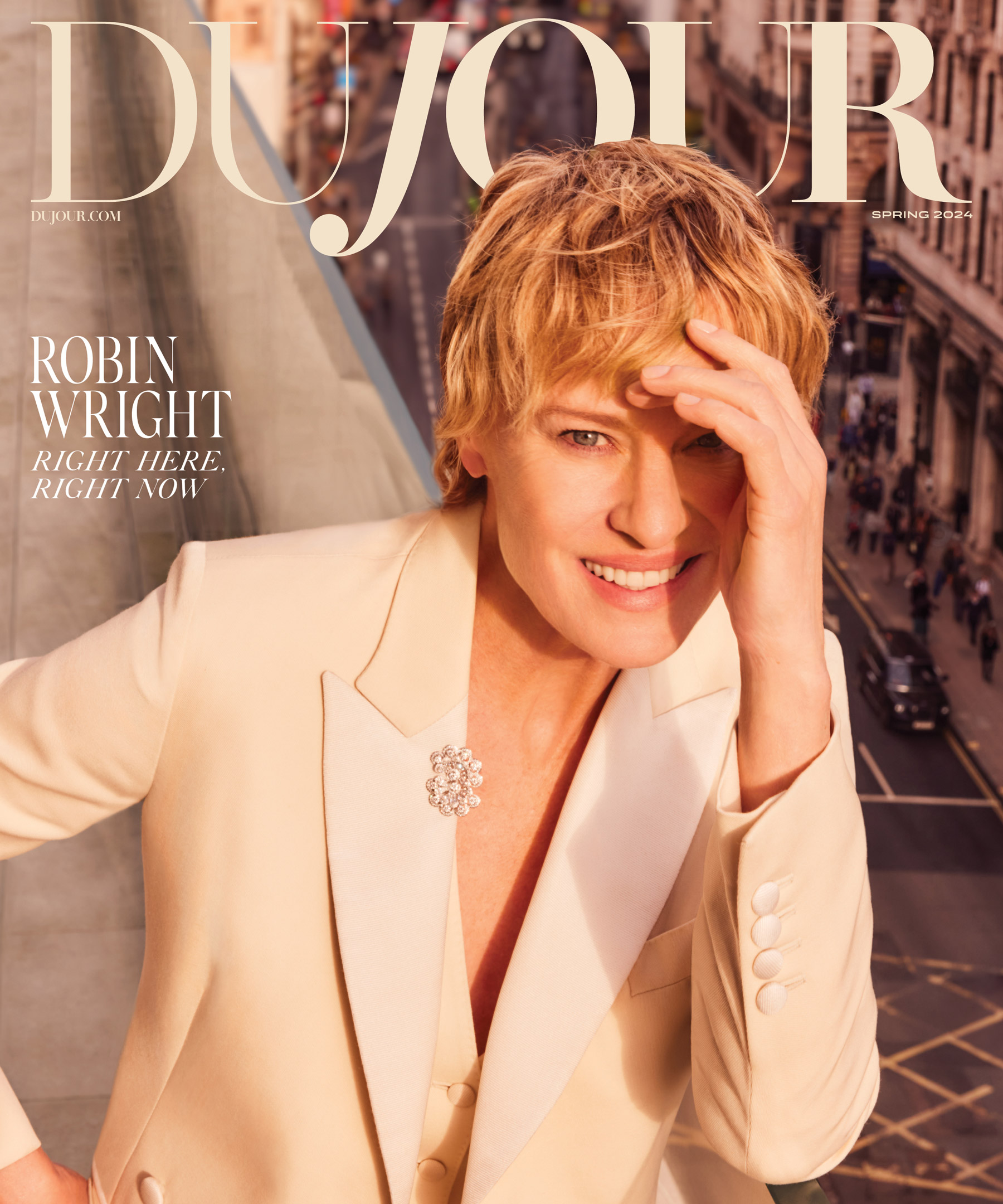

A Loa water frog.

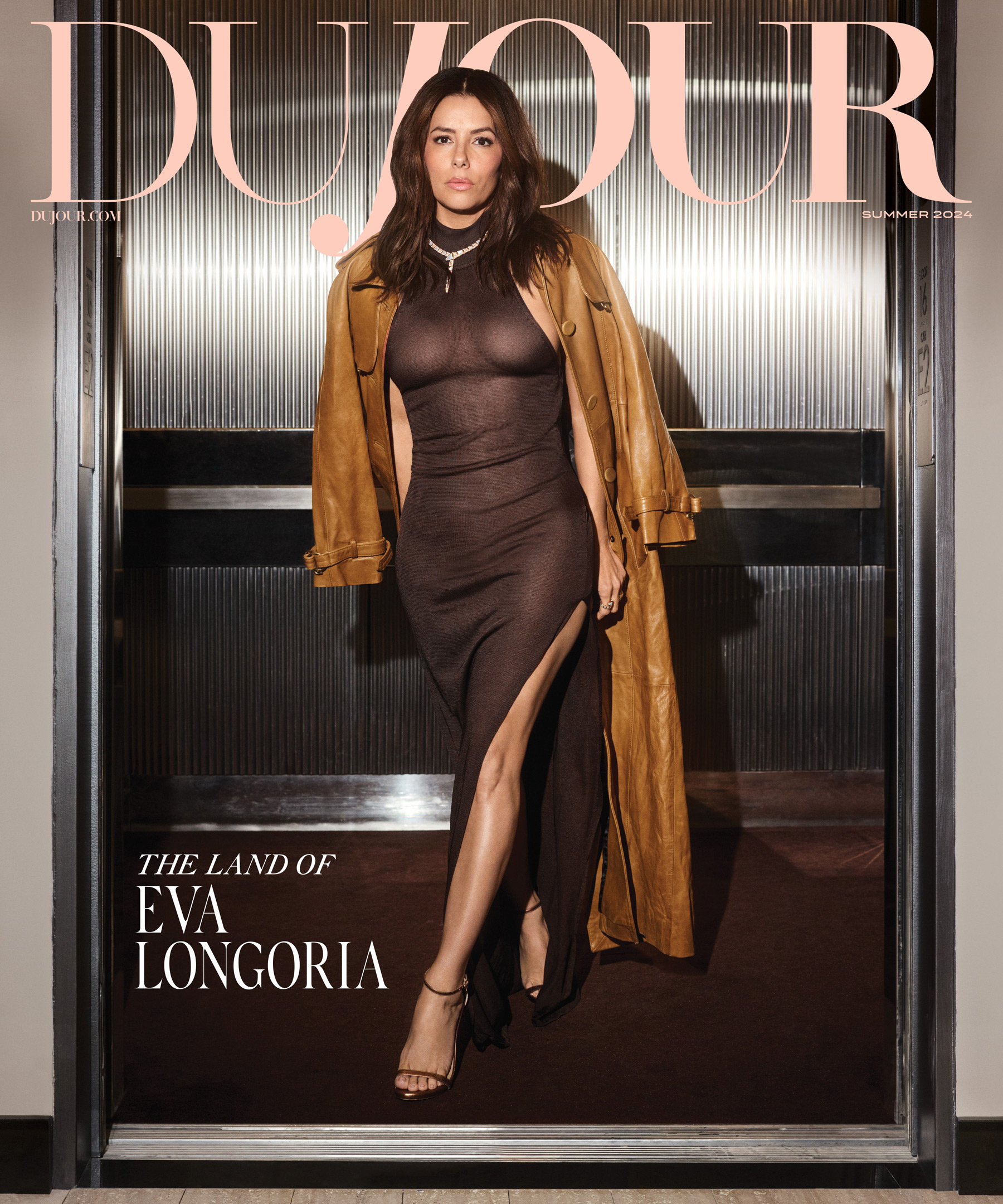

This was no sentimental save. Frogs breathe through their skin as well as their lungs, and are consequently extra sensitive to changes in their environment, making them key indicators of water quality. When water frogs show signs of stress, they become the proverbial canary in the coal mine: Their declining health is a sign of declining water quality—or quantity—and immediate attention should be paid. This past June, a team of conservationists, government officials, and indigenous leaders on a relatively routine visit outside the city of Calama, in the middle of Chile’s Atacama Desert, discovered that the already limited habitat of the Loa water frog had nearly dried up entirely. The remaining 14 frogs, all of them skinny and malnourished, had been pushed into a tiny pool of muddy water, awaiting the inevitable. The team collected them and brought them to the National Zoo of Chile, where the zoo’s specialists have been nursing their charges back to health and talking to water frog experts around the world about how best to care for and eventually breed them.

A number of international wildlife organizations—including Amphibian Ark, the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group, the Amphibian Survival Alliance, and Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC)—have also called on the government of Chile to solidify and expand on this great work by addressing the larger matter of halting activities that threaten the Loa water frog, restoring its habitat, and formally protecting it as a sanctuary or reserve that is regularly monitored. “The first big challenge is to help these frogs survive,” said Alejandra Montalba, director of the National Zoo of Chile. “While the rescue was the best chance to save the Loa water frog, there are always risks with trying to care for a new species—especially when the animals are already struggling. That’s the main goal right now. Later we need to be able to breed them. But ultimately we need to work very hard to restore their environment, because it’s pointless to breed them if they don’t have a home to go back to in the wild.”

“What will happen to the frogs in Chile will happen to the people here in the not too distant future,” said Andrés Charrier, a herpetologist with the Chilean Herpetological Society, and rescue mission member. “If the frogs from the high mountains from Santiago start dying because their rivers go dry, we will have no water to drink in Santiago. These connections are critical.” The government of Chile is now conducting an investigation into copper mining companies that may have been responsible for draining the Loa water frogs’ habitat. The threats to the Loa water frog are common throughout northern Chile, where water is a scarce resource, drought has been unrelenting, and additional pressure comes from multiple human sources. The land that includes the muddy pool where the frogs were found, for example, was recently sold to a real estate developer. The agricultural sector has also diverted irrigation canals to take the groundwater. So in addition to making sure the Loa water frogs’ creek flows again someday, conservationists want to see the government of Chile commit to a long-term research and conservation plan for all of the country’s water frogs, including, in some cases, conservation breeding programs.

Loa water frog during a rescue operation near the northern Chilean city of Calama.

Multiple voices are being raised to defend the frogs and the environment on which both they and the human population depend. Even environmental activist and Academy Award–winning actor Leonardo DiCaprio has joined the international call to protect the species and its habitat, writing on Instagram: “The government of Chile and a team of conservationists have done an incredible job responding swiftly to try to rescue the Loa Water Frog from extinction, bringing the last few to the National Zoo of Chile to be nursed back to health. Share this message to encourage continued actions to #SaveTheLoaFrog! Share to spread the word. #SalvemosLasRanitasDelLoa.”

Another celebrity has also helped share the story of the Loa water frog: Romeo the Seheuncas water frog (a cousin species to the Loa water frog), once known as “the world’s loneliest frog.” In 2008, a team of biologists in Bolivia brought Romeo to the Museo de Historia Natural Alcide d’Orbigny in Cochabamba. They hoped to create a conservation breeding program for the traditionally common species to get ahead of the population crashes they were seeing with other frogs. But ten years later, they had not been able to find a single other individual Sehuencas water frog—male or female. So in 2018, GWC, the Alcide d’Orbigny Natural History Museum, and Match, the world’s largest relationship company, created an online dating profile for Romeo. The profile helped raise enough money to send a team into the field in a last-ditch effort to look for other frogs. They were successful, bringing back a number of Sehuencas individuals, including a Juliet for Romeo.

The Sehuencas water frog team has been among the experts helping to advise the National Zoo of Chile. Romeo recently wrote a letter to the Loa water frogs at the National Zoo in Chile, encouraging them not to lose hope, and “narrated” a video, in both Spanish and English, about their plight. There are at least 63 known species of water frogs found from Ecuador to Chile, including in Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina. Many of these species, like the Loa, are microendemic, which means they live in just one small place. Pollution, disease, and invasive trout are among the threats they face in addition to habitat destruction. About 10 species of water frog live in Chile, and many of them are likely facing the same threats as the Loa water frog.

“Global Wildlife Conservation is proud to be committed to the conservation of water frogs, a unique and charismatic group of frogs that have gained notoriety over the last few years thanks to Romeo the Sehuencas water frog,” says Don Church, GWC’s president. “The story of the Loa water frogs is a cautionary tale, one that should spur us to action for all other water frog species before they decline to only a few individuals left.”

Thanks to swift and bold human intervention, the Loa remains with us, a cautionary tale indeed, but also a beacon of hope for the future of water frogs—and of our planet.