You’ve got to hand it to Ben Lee: he is sticking to the beat of his own drum. To his credit, it’s been a catchy beat for some 20 years now. The world took official notice back in 2005 when, reeling from a breakup with Claire Danes, he released the ARIA-winning album Awake is the New Sleep. Hit tracks like “Catch My Disease” and “We’re All in This Together” reveled in an insistent simplicity: the truths most worthwhile are not complicated, and there’s no point in saying them in a complicated way. Over the years Lee has weathered criticism that his work is guilelessly sincere, but he seems unconcerned by this, and his latest album, Love is the Great Rebellion, reiterates his philosophy with a newfound certainty. The new father of a little girl, his commitment to a universal and unpretentious language of love has only grown stronger.

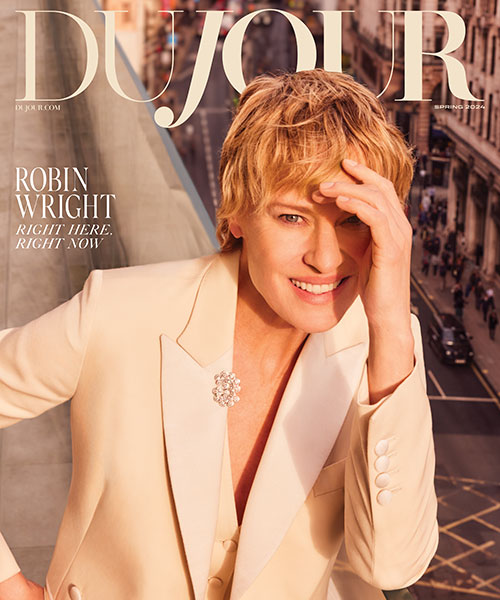

Lee’s musical career began in the mid-nineties at the ripe age of fourteen as a part of the Sydney-based band Noise Addict. He launched a solo career after he was picked up by producer Brad Wood and featured on the soundtrack of There’s Something About Mary. His career has since held strong at a steady clip, and his later interest in QiGong, an Eastern system of healing and energy medicine, inspired his previous album, Ayahuasca: Welcome to the Work. Lee sat down with DuJour to chat about the lessons he’s learned and the messages he hopes to share with listeners.

What do you want to get across with this album?

It would be about the courage it takes to radically change. The kind of rebellion I’m talking about is the rebellion against ourselves. It’s looking at oneself in the mirror and saying, “I don’t like what I see, so I’m going to think differently from now on,” with a kind of sobriety, but without getting trapped in depression or self-punishment—just actually changing. It’s one of the most harrowing things that someone can do.

In a few of the songs, like “God Is the Fire,” is there a religious message?

I’m not really concerned with orthodoxy in any religion. I do believe in true revelation—people actually having experiences, and that’s the real power of the Qur’an, the Bible or the Torah. They speak of these transcendental states, but they’re an incredibly volatile and potent force. It’s funny; sometimes we feel this pressure to readjust our language for the sake of not offending people. Why aren’t we saying what we mean? To me, that’s what this song is about: God is a fire, God is the thing that burns in us and leaves us standing in the trees. It’s just about redefining words and not being afraid of the ones that ring true.

Is there a crucial difference between the messages in Love Is The Great Rebellion and Awake is the New Sleep?

The difference for me was that Awake is the New Sleep had a youthful exuberance that wasn’t overtly grounded in hard work. It was kind of like falling in love. You fall in love and it feels like you’ve solved your problems, but then six months later, you realize you’re actually the same person with the same problems—and if you want to permanently move into that happy state of consciousness, you have to really start working on maintaining that relationship. I suppose Awake is the New Sleep is like falling in love with spirituality, and Love Is The Great Rebellion is more grounded in hard-standing work. That’s why the first song in the album is like, I’m giving up on miracles. Miracles embody a belief that you can achieve something not based on your hard work.

One of your trademarks is that you’re not afraid to say things simply, which has received some criticism. What is your philosophy behind writing lyrics?

I’ve always equated it to comedy. To make people laugh usually requires intelligence. People confuse simplicity with naivety, and I don’t think that’s always the case. We can choose to be simple because we’ve examined the options and we believe it’s the best option… I think to just write things off as unintelligent because they’re said simply is a mistake.

Do you feel like dismissing things that seem overly simplified is an instinct of our culture at this moment, or that people have always been like that?

I think there’s a bit of an infatuation with academia, where we read something and if it’s incomprehensible, we assume it must be true. We go, “Ah, that person must be really intelligent, because that’s something I don’t understand at all.” But I think we all have a part of us that respond to the truth. You can feel it in your body.