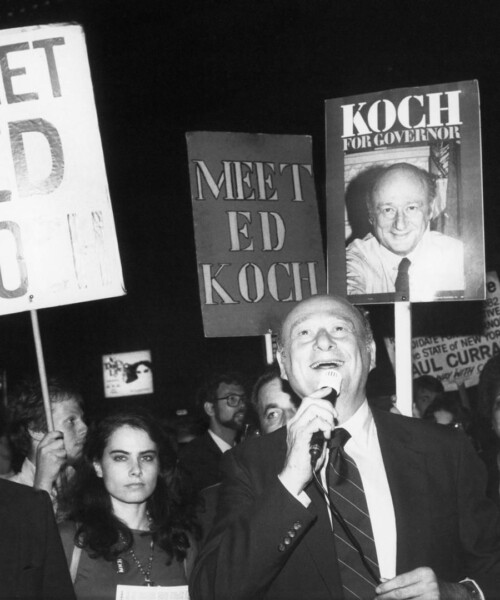

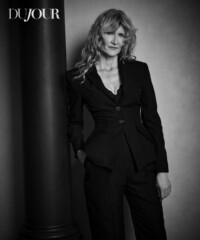

Ed Koch—who passed away this morning from congestive heart failure at the age of 88—was the outspoken, divisive but ultimatedly adored mayor of New York City from 1978 to 1989. He was the man in charge when the subway workers went on strike for 10 days, when a beloved Harlem hospital closed, and when the AIDS epidemic was at its height. He was also a larger-than-life leader who made appearances on Saturday Night Live, hit the town with former Miss America Bess Myerson (supposedly to quash rumors he preferred the company of men), and presided over extraordinary overhauls to the city government.

Starting on Feb. 1, the ups and the downs of Koch’s 11 years in office—and his not-entirely-quiet life afterwards—will be on display when filmmaker Neil Barsky’s documentary Koch plays in theaters. A few weeks ago, DuJour met with Koch in his office at a Manhattan law firm to discuss the film, the prospect of an openly gay New York City mayor, and what it’s like having a bridge named for you.

What made you decide Koch was a project to get involved in?

It wasn’t me. Neil Barsky called Diane Coffey, who’d been my chief of staff and is my close friend, and he told her what he wanted to do. Then she called me and said she thought it was a good idea. She said, ‘Why don’t you talk to him and if you think he’s fair, do it.’ So I did talk to him and I only had one request: Before you make it public, show it to me and allow me to express if there were things that should be corrected and he’d decide whether or not to make the changes. When he showed me the film, I requested no changes.

One of the bigger events in the film is the closing of Sydenham Hospital. You said on camera that you would have handled it differently. How?

On the merits, I did the right thing. But the merits in this case were the wrong thing. Every mayor before me had said they would close the hospital because it provided inferior care and cost more per patient that Bellevue. What I didn’t take into consideration, which the other mayors did, was the psychological impact of closing the hospital. It had been created by the black community when black doctors couldn’t admit their patients into hospitals operated as white hospitals. The community didn’t care about the healthcare as much as the hospital, which was something special. I didn’t appreciate that.

How do you think the famous ‘Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo’ posters affected your 1977 mayoral race?

I think that people when they voted for me, some thought I was gay, some thought I wasn’t, most didn’t care. It probably affected my friends more than the public. I don’t think it added to my vote, but I don’t think it significantly detracted from it.

We have a New York City mayoral race coming up with an openly gay candidate, Christine Quinn. Are you surprised that her sexuality is seemingly not an issue?

You say it’s not an issue, but there are 50 states in the union and only 20 of them have laws—I was responsible for the city of New York—that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. [Homophobia] is not something I’d say has gone away. In the state of New York, it’s much different than it used to be. In other states, not so much.

But is watching someone like Quinn run moving?

I think it’s marvelous. I helped make that happen, and I’m very proud of that. Remember that in the first month of my administration, I issued an executive order barring discrimination based on such things. People were shocked.

Throughout the film, the power of the press is apparent. The newspapers were hugely important. What do you think today is the most powerful outlet in New York City politics?

The New York Times, because there is no other media institution that, if they support you, will bring you the same large percentage. It’s the number-one endorsement. Though I didn’t have it, I was not endorsed by the Times; Cuomo was.

You say on camera that if you’d been elected to a fourth term, you’d have died in office. What about the job makes it that lethal?

It’s 24 hours a day. I once said, early on, that if you want to pick at the President it’ll cost you $400 round trip to go to Washington. If you want to pick at the governor, it’ll cost you $200 to go to Albany. You want to pick at me, it’s $3 round trip. And they came.

At one point in the film, you visit your already erected headstone. There’s an epitaph written, but what is it you’d like your legacy to be?

This is what I did for the city of New York: Everybody thought it was going to become Detroit, but I saved it. I rebuilt it. The first thing I did was give people back their sense of pride. The second thing was that I balanced the budget for the first time in 15 years. Third, I rebuilt the city with 250,000 affordable apartments. Not bad for a kid born in the Bronx.

You’ve made a business lately of writing film reviews. How did this start?

I’ve always gone to the movies. I don’t pretend to be an expert, though, and that’s what makes my reviews so likeable. People enjoy them; I have a mailing list of 6,000.

You’ve got a bridge named after you, the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge (what used to be the 59th Street bridge). What does one do with a bridge once it’s named for him?

I make a point of joking about it. My major joke is that I’m looking for a canvas cover for it for inclement weather—but off the shelf, otherwise it’ll be too expensive. I also think there should be more lights on my bridge.