Few Americans, let alone doctors, have the Q factor of Dr. Mehmet Oz. It begins with his impeccable medical credentials: A graduate of both Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania, he is vice-chair of the department of surgery at Columbia University School of Medicine. With an eponymous TV show and magazine, he’s committed to connecting with patients and helping them get and stay well. Finally, he’s fascinated with alternative treatments like herbs and Reiki that Western medicine doesn’t necessarily endorse (just ask that Senate committee that grilled him) but which people have believed in for centuries.

In a development not unconnected to these credentials, Dr. Oz’s net worth is estimated at $14 million.

He’s not the first star in this brand of medicine. Dr. Andrew Weil, also educated at Harvard, is considered the founding father. He started the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine (think of it as the Hogwarts of the discipline) in 1994. Dr. Weil’s name accompanies beauty, food and health products; his books sell in the millions. Aside from Weil and Oz, doctors like Frank Lipman and Mitchell L. Gaynor have built impressive reputation—and businesses—by embracing integrative medicine.

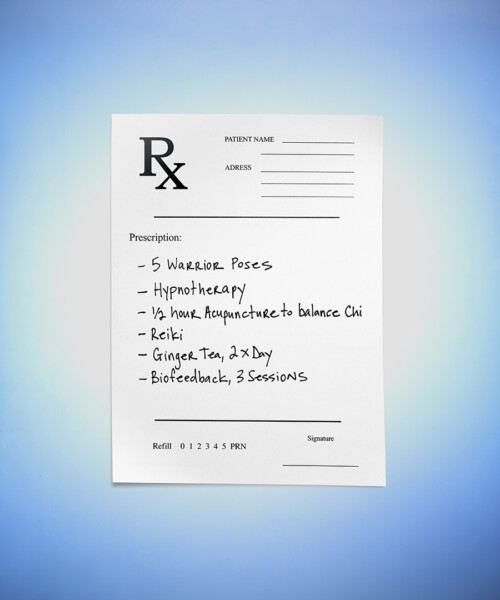

These doctors have conventional credentials but are willing to consider less-conventional techniques. Integrative medicine usually includes a collaborative provider-patient relationship, an emphasis on preventive care and wellness, and the use of alternative (and, critics say, unproven) therapies like acupuncture and biofeedback. So you may receive conventional medicine for a broken leg or infection and alternative remedies for allergies. Patients can get the best of both worlds.

Not surprisingly, the combo doesn’t come cheap. Many insurance companies have been unwilling to pay integrative doctors for the extra time they

spend or cover certain treatments. “Insurance and the current reimbursement schema create obstacles for physicians ready to adopt integrative medical practices,” says Nancy Sudak, executive director of the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine. Many doctors who want to go integrative stop accepting insurance and shift to fee-for-service or concierge services. Indeed, according to Erik L. Goldman, editor of Holistic Primary Care, a big trend is for physicians to go the direct-pay route.

“The growth of integrative medicine is demand driven, and people who are well enough off to be able to pay for their own health care are the early adopters—look at celebrities,” says Tabatha Parker, ND, director of education at AIHM. “They want a higher level of care and more attention than they can expect from an overworked doctor who has eight minutes, and they’re used to getting what they want.”

It’s no surprise that celebrities were linked with the first wave of integrative doctors. As long ago as 1995, People reported that Ted Danson and Bill Moyers sought the advice of integrative cardiologist Dr. Dean Ornish. Even if you’re not impressed with how Gwyneth Paltrow or Suzanne Somers stay healthy, it’s worth noting that Bill and Hillary Clinton have long taken advice from integrative guru Dr. Mark Hyman, while Arianna Huffington is reportedly a client of Dr. Lipman’s. This may explain why many of these doctors specialize in weight loss, anti-aging treatments, detox and hormone-replacement therapy.

Its supporters insist, however, that the landscape is changing and integrative medicine is more broadly accessible. “Legislators and health-care administrators recognize its efficacy and cost-effectiveness,” says Dr. Parker.

Though there are no hard statistics on how many doctors have jumped on the bandwagon, it appears the numbers are growing. Victoria Maizes, executive director of the Arizona Center, says that their fellowship program has expanded from four slots in 1997 to 130 doctors a year today—with

a waiting list. And the field’s also gaining in respectability. In 2014, the American Board of Physician Specialties became the first multi-specialty group to offer doctors board certification in integrative medicine.

What’s ironic about this upswing is that, while integrative medicine has done well by its famous advocates, for a long time it was perceived among doctors as anything but a fast track to riches. “You don’t go the holistic route to make money,” insists Goldman. In many cases, a doctor gets paid more to spend five minutes prescribing a pill to lower LDL cholesterol than to take 15 minutes to explain diet and exercise changes to help lower bad cholesterol naturally. Many of the alternative services doctors recommend, like acupuncture or Reiki, they don’t perform themselves—they make referrals.

Sometimes the conversion is driven by personal experience. Take Richard Ash, an innovative Fifth Avenue doctor who’s written several books and has a call-in radio show. Years ago, while a conventional internist, he developed inflammatory arthritis. When he sought treatment, he was put on 20 mg of prednisone per day—for two and a half years. “It worked at first but wreaked havoc on my health,” Dr. Ash says. “My blood pressure, my weight. The side effects were terrible. The drug should be used as a Band-Aid for emergencies, not a long-term solution.” He researched and investigated alternative remedies, and slowly started to change his diet and lifestyle to minimize his body’s acidity and inflammation. Over an eight-month period, he weaned himself from the drugs. “It changed my life, my health and the way I practice medicine.”

Though doctors may never have a high-powered integrative medical empire with patients decamping from insurance, “a thriving practice is now possible,” says Sudak. Some doctors may add services like oxygen therapy or sell supplements, which can provide extra revenue. Others may start group classes, in which several patients with the same issue will get more intensive preventive education together and then have shorter individual visits.

Dr. Patrick Fratellone, a respected Madison Avenue integrative cardiologist, says the emphasis is on remembering the old as much as discovering the new. His own congenital heart issues led him to herbology. He may spend over an hour on a visit, asking patients about their lives, discussing how they should shop for food, prescribing exercise. Sometimes he gives patients herbal teas customized to treat their problems. “I’m going back to the roots of medicine,” says Dr. Fratellone. “Like an old-time country doctor—except we don’t have those anymore.”

While some MDs may not have the “entrepreneurial gene” to become a business superstar, more and more docs are finding the personal and professional rewards of integrative medicine reason enough to change. Says Goldman, “It really depends, whether a doctor who switches to integrative medicine makes more money or less. But I don’t know any who regret it.”

NEXT: A comprehensive list of our favorite integrative medicine physicians