By the second hour of hiking up to Tiger’s Nest—Bhutan’s most photographed pilgrimage site—a person begins to make sense of Buddhism. The experience is meditative. Your thighs are searing. You can’t get enough oxygen into your lungs. Your mind clears. The only thought is: Put. One foot. In front. Of the other.

Most climbers spend a full two hours counting the steps to the top (about 40,000, according to my iPhone’s Health Dashboard), and all who make it past the cafe sneakily placed at the end of the “easy” part of the journey are rewarded with that iconic view seen on every travel magazine cover since former king Jigme Singye Wangchuk, affectionately known as K4, opened his empire to tourism in 1974. And that’s only the half of it: The hike down is much harder.

In fact, all of Bhutan is much harder. I had booked my eight-day journey through Boston’s Audley Travel, which, along with the exceedingly wise guides at the country’s handful of Amankora resorts, had orchestrated transfers between four of the five lodges tucked deep within vastly different glacial valleys, as well as the usual mind-blowing Aman activities (a private prayer-flag printing class, a traditional hot stone bath in a potato field) and some rather unusual, personalized ones (cocktails with a proper princess, lunch in an authentic farmhouse). On paper, the trip seemed straightforward and quite manageable. But in Bhutan, I’d learn, nothing is truly as it appears.

Maybe I should have read the fine print—that all five Amankoras are equipped with oxygen chambers and that travelers not in good health should skip the arduous hike up to the Tiger’s Nest, the unofficial name of the 17th-century Taktsang Palphug Monastery, where the great Guru Rinpoche supposedly arrived by flying cat to meditate for three years, three months, three days and three hours. Or maybe it’s best that I didn’t know what I was getting into as I tossed my running shoes and a few pashminas into my Rimowa hard case. Blind discovery is half the adventure, right?

Nonetheless, the difficulty of “doing” Bhutan should have become apparent from that initial descent. Seasoned fliers will tell you that the landing at Paro Airport is one of the most frightening in the world. (Aspen and St. Barth’s: We mean you.) Though Paro is not the capital, it benefits from tourism dollars since it lays claim to one of only two valleys wide enough—only just—to allow the wingspan to eke its way around a bend and, boom!, into a ravine that sits more than 7,000 feet above sea level. As we banked along the pine-strewn hills that jutted up against the runway, I could have plucked a bough had my window been open.

Rather than granting me an early indication that Bhutan might be extreme travel—that I should give up the fantasy that the Switzerland-sized country would be an “easier” Nepal, all snow-capped peaks and hippie Internet cafes, or that its 700,000 inhabitants occupied a more welcoming environment than high-desert Ladakh, India, where scarves to block the sand devils were essential accessories—the hard landing gave me a palpable thrill. No one I knew had ever traveled to Bhutan, and it had been on my wish list since I got my first grown-up passport in college. That tight descent signified I had arrived somewhere significant, a place where a king peacefully abdicated to his young son (K5) in 2006, who quickly held democratic elections, where health care and education were free to everyone. But like the tangles of flags that elegantly sway in the wind at the top of every mountain pass, sending their secret prayers into the heavens and beyond, the country’s hidden meaning would take weeks, if not months, to fully permeate my consciousness.

Few visitors, tourism officials will tell you, make the trek to Bhutan. Some 133,000 international and regional travelers made the journey in 2014 (only 27,000 were American), up from 23,000 in 2009. The official goal is to bring that number to 200,000 by 2020, with hotels like Le Méridien, Six Senses and even midmarket Accor set to open locations this year and next. The switchbacks are getting paved and recut, courtesy of Indian dollars, and smooth transfers between valleys might even be possible by 2018. A new helicopter charter is about to launch, and not one but two airlines now offer internal (to Bumthang) and external (to India) service. Backpackers will still have a hard time thumbing it across valleys—by law, all trips must be pre-booked and pre-paid—but the myth that Bhutan is available only to the uber-wealthy is reluctantly being dispelled. Though the kingdom does require a $250 per person, per day “tariff,” that fee has been, shall we say, intentionally misconstrued to denote it lies on top of your daily spend. Not true: For just $250 you get a minimum three-star hotel, of which there are many lovely ones; your own licensed guide; a private car and driver including petrol; and all your meals and park entries. (Just $65 of it goes directly to the government.) Not quite India-cheap, but accessible to most. Still, the genius marketing misconception of the “tariff” has kept the riffraff at bay and allowed Amanresorts, the dominant hotel group in the country, to control the experience on the ground. Which is to say, getting to Bhutan before everything sparkly and new and—gasp!—mass comes online in 2018 might be comparable to the difference between visiting Cuba before Obama eases travel sanctions and after.

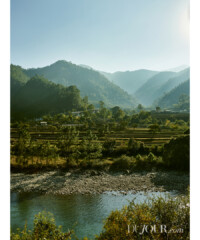

Refreshing for a quick night in the capital of Thimphu, I begin my early-morning, seven-hour journey to Gangtey, in the Phobjikba glacial valley, thick with ghostly birch, juniper and spruce and, in the near distance, the wail of the endangered black-necked cranes who migrate here from Tibet in the winter. The unpaved road hairpins up 12,000 feet to a viewpoint of dozens of white stupa whose backdrop is the dramatic Himalayas, silver with snow as I had imagined. A man is busy at work burning mounds of detached prayer flags that have long since lost their luster; to burn them is to pay homage to the dead. I desperately eat the ginger chews my traditionally dressed guide (it’s also the law) has thoughtfully planted in my car kit—sunblock, lip balm, water, wipes included—to stave off the motion sickness. The only straight road in Bhutan, the joke goes, is the runway at Paro.

Most visitors prefer Gangtey of all the Amankora lodges, and its eight rooms are hard to hyperbolize. Sleek yet simple, created from poured concrete and teak, the main building stands sentry over the cranes and the U-shaped misty valley below, with the mythical 17th-century Gangtey Goemba to the west. To hike there, you pass roadside yaks and enter an enchanted forest of old-growth rhododendron draped in spider webs of Spanish moss, then slope up toward the hilltop monastery. Inside its stucco walls are padlocked doors only mystics and kings can enter; rumor has it a Yeti carcass is secreted behind one, along with armor and other ancient finds from a 15th-century treasure hunter. Every surface is painted in Tantric Buddhist imagery that defies explanation: a Garuda, evil spirits with multiple heads, yak-butter candles dedicated to Buddha, an endless array of phalluses. I’m mesmerized. I spend hours at the dzong, trying to sort out the story line on the walls. An endless hot stone bath in an outdoor barn—boulders carried on tongs by an octogenarian woman, her youthful partner sipping tea on a log—helps it all sink in, quite literally, as the sun sets beyond the valley walls. Was I in the midst of the spiritual transformation I’d anticipated?

We moved fast but we moved slowly. In another day, we’d be headed to the Mad Monk’s temple on our way to Punakha, the ancient capital and former summer retreat of the royal family. From the road, you must cross a hanging bridge that surely inspired a scene from Indiana Jones, its planks swaying precariously above the Mo Chhu river. The rooms at all of the five Amankora properties are nearly identical, so figuring out how to light your bukhari stove or where the American outlets are positioned is easy despite so much moving between lodges. Bhutan becomes familiar and indecipherably other at the same time. Time passes at its own unworldly pace.

In Punakha, I drop my bags, then explore a guava-tree orchard ripe with fruit, and pick up dribbles of WiFi on a lounge chair fronting the languid river. I apply layers of that sunblock from my car kit. We may be around 10,000 feet up, but Punakha is somehow subtropical, and temperatures hit nearly 70 at peak sun. When it cools off, my guide, Max, and I hike through the tapestry of rice paddies that cut into the hillside up to the old temple Giligang and the fortified Punakha Dzong. I’m wearing my sneakers as we run down, whisking past farm boys and their oxen, townspeople selling small baskets of tomatillos and young farmers weighing rice into fabric sacks. A final stop at the weekly market to buy spices and prayer flags to carry stateside ends the day. Around the light of a fire on the stone terrace, we dance with a local troupe and devour bowls of Bhutanese stews, reputed to be some of the worst cuisine in the world (though the chef imported from Amangani does his best), made with meat killed in other countries, since the slaying of animals in the kingdom is outlawed by Bhutan’s Buddhist tenets. Yet another of Bhutan’s many contradictions, its binary allure.

The final chapter of Bhutan is always Paro and the hike up to Tiger’s Nest. Saving it for last makes absolute sense. This allows you to retrace your mental steps and congeal your thoughts, recalling all those ineffable moments that elude your memory and your journal: Shooting crossbows with Olympic champions at some roadside park. Picnicking at the confluence of sapphire-blue rivers. Awaiting the explosive burn of peppers with yak cheese in a farm woman’s kitchen to dissipate. Turning the prayer wheels at the dzongs and hoping those kind thoughts of relatives made their way back home on the Himalayan breeze. Having been blessed by a monk with a red string in Thimpu on my first day and by a prostrate disciple on the last, I obsessively touch the necklace still hung around my neck and wonder where I’ll burn it, as suggested, or if I’ll allow it to fall off on its own and grant my deepest desires.

I take off my shoes and walk the temple ramparts at the top. A stuffed tiger teeters on a ledge, a reminder of the Guru Rinpoche’s original conduit. They say that tigers did once roam here, up where a mystical palace clings to a vertiginous cliff. But most people I met in my week’s stay hinted that what you hear in Bhutan is not always the true message—that K4’s idea of tallying Gross National Happiness instead of Gross National Product was a silly aside, a kind of inside joke that has become the country’s most famed marketing campaign; or that the $250 per day required spend was intentionally called a “tariff” to throw off the backpackers; or that preserving 60 percent of the country as a nature reserve was a means to keep pollution (and India) out and a sustainable industry of hydropower in. The country was given its name by a British explorer who derived it from the lingua franca for “Land of the Thunder Dragon,” but I’m beginning to believe it more accurately translates to “double meaning.” Or, “Figure it out for yourself.”

As my legs scream and my lungs ache, and I pass one, maybe three, other travelers on the trek to the country’s photogenic monastery, I decide that hidden truths and layered intentions are the point of Bhutan. You’re meant to peel them like an onion on your own, slowly, whether you packed the right clothing or the right attitude, read every negative review on Tripadvisor or willingly believed the transcendent praise in hotel guest books. Gross national happiness? Hard to quantify, even in the government-sanctioned surveys. A spiritual Shangri-La? Not quite, at least not while you’re still “doing” Bhutan and feeling the burn.

It didn’t take me three years, three months, three days and three hours to figure this all out. On the final stretch of my final descent back to the trailhead of the Tiger’s Nest, my thoughts simplify and my goals for the near future crystallize. Clarity is mine, and, I assume, everyone else’s hiking down the cliff. I touch my red necklace and decide to keep it intact until I arrive back home and Bhutan’s veiled truths are ultimately made plain. A trailside sign appears, speaking directly to me: “Life is a journey. Complete it.”