One of the biggest (so to speak) trends in restaurants today is the large-format meal, a pre-booked, chef-designed menu, usually offered to groups of five to fifteen. Inspired, in part, by the nose-to-tail movement, the concept rewards adventurous eaters as well as anyone who loves to indulge. But a surprising portion of the meals’ appeal derives from the opportunity to host a dinner party outside one’s own home; the company, it seems, is as important as the (unquestionably delicious) food.

As seen on theSkimm, subscribe here for more.

The rotisserie-duck meal at Momofuku Ssäm Bar in New York’s East Village is (rightly) counted among the city’s most glorious gastronomic pleasures—right up there with Masa’s lavish, $600-a-mouth omakase and the Peter Luger porterhouse in that pantheon of actually-worth-it foodie badges. Served to parties of three to six (at exactly one table per seating), the star of this family-style meal—what has been termed “large-format” dining—is a local beauty from Long Island’s Crescent Farms, prepped and roasted to burnished-mahogany perfection under the watchful eye of superstar chef David Chang and his trusted delegates.

But it isn’t the pitch-perfect sourcing that makes this avian feast so special. Nor is it Chang’s cult cachet—though for sure that makes this duck all the more coveted. Rather, it’s the unassuming layer of house-made pork-and-duck sausage tucked between the breast meat and the skin. To the untrained eye, that deft, nuanced move might simply read as garden-variety porcine gratuitousness. But as anyone who has ever tried to cook (or even just eat) a duck knows, the disproportionately hefty layer of fat just under the skin is, quite literally, a big fat problem. Simply put, unless you’re willing to overcook the breast, there’s not enough time to melt enough of the fat layer without employing a host of tricks, most of which are inadequate, leaving you with dry breast meat, globs of chewy fat, or both. Therein lies the culinary sleight-of-hand, and why Chang—who cooks his duck to perfection—fills tables months in advance.

Ssäm Bar’s rotisserie duck is just one of 13 large-format offerings throughout Chang’s Momofuku empire, and they, along with large-format dinners at other top spots, represent some of the country’s hardest reservations to snag. My first experience with large-format dining was Chang’s bo ssäm dinner, which includes a whole slow-roasted shoulder of Niman Ranch pig, served with a dozen oysters, white rice, Bibb lettuce and a variety of sauces. The food is exemplary—salty and fragrant and deliciously intense—but the fun is in the format (and, not for nothing, a VIP table in an otherwise unreservable restaurant). Groups of 6 to 10 are encouraged to assemble their own wraps and otherwise help themselves, as they might at an intimate gathering at someone’s home. The feel is like Thanksgiving, but you get to choose your family, don’t need to cook and can leave before cleanup.

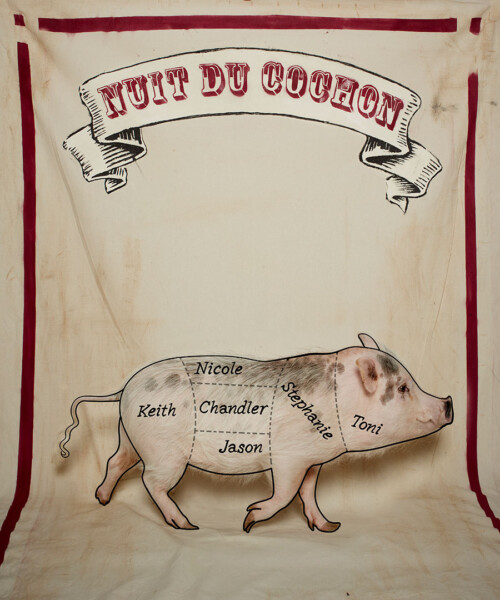

Chang, of course, did not invent large-format dining. It’s a concept as old as Adam—or at least Moses, who played beleaguered sous to the holiest of hands-on chefs in Exodus 12:5, when tasked with prepping slaughtered lamb for an unruly 600,000-top. Later came medieval ox feasts, then pilgrim tryptophan banquets and eventually backyard pig roasts galore. In its restaurant incarnation, though, the large-format craze emerged as a spin-off (or amalgam) of three modern dining trends. First, the nose-to-tail movement, wherein chefs began butchering in-house and, thus, had entire animals in the walk-in. Second, the Cult of Pig, in which diners became obsessed with all things cochon. Finally (and perhaps counterintuitively), the small-plates revolution, which undercut the rigid tripartite meal structure of the app-entree-soufflé era and ushered in a far more relaxed view of both portioning and pacing.

That said, with his inaugural bo ssäm dinner, Chang made the large-format concept popular and, more significantly, cool. Suddenly, the family-style floodgates opened, emboldening restaurant kitchens to branch out to other creatures, great and smallish. If diners were willing to take the initiative and band together to share an entire suckling pig, how about partial cows, say, or multiple chickens? Now top restaurants in every major (and aspiring) food city have dared to dabble in the beauty of the beast-for-a-crowd. At the Breslin, the gastropub inside New York’s Ace Hotel, chef April Bloomfield offers a curry lamb for parties of 10 to 12 at a prime center table; Ed Schoenfeld’s new Decoy, meanwhile, operates exclusively on a large-format concept.

“It’s fun to go and share. It’s the emotional part of it,” says Schoenfeld. “In an era where food is often the main event of the evening, one of the things that’s attractive about this type of meal is that it’s curated, it’s special, it’s an experience.”

Throughout the country, dining has evolved to be a very convivial thing. “There was a time when you got dressed up in your best clothes and went to a fancy restaurant to celebrate a special occasion or sign a business deal, but [today], restaurants have become a platform for entertainment,” says Michael Psilakis, who serves large-format meals at his NYC restaurants Kefi and MP Taverna. “The meal is just the mechanism that brings people [together]. The company is the star of the show.”

Of course, landing a reservation for one of Chang’s tables—or Bloomfield’s, or Schoenfeld’s—is no small feat. You have to be willing to work. To book a table at Momofuku, you need to call exactly four weeks before your desired date. Twenty four hours before, they will ask for a final head count, and everyone must show. This means you can’t invite your flakier friends to this particular party. You will also disqualify vegans, as well as generally picky eaters for whom a game bird or a pig butt would prove too Fear Factor. But maybe that’s okay.

In fact, perhaps the most appealing thing about large-format dining is that, as host, you can call the shots in a way that you just can’t anymore at home. As someone who loves to cook for friends and family, assembling a dinner according to someone else’s rules absolves me from having to accommodate my friends’ every eating habit or schedule restriction du jour. In a way, it lets me serve what I want to serve, or at least what I want to eat. For the nurturer/pleaser/consummate-host type, this is incredibly freeing. Witness some sample texts from my own duck lunch:

Them: Sounds fun, but babysitter can’t come till noon, OK to make it 1?

Me: Wish I could, but they’re strict—15 minutes late and we lose table.

Them: Not so big on duck but love to hang. What else they got?

Me: Ooh, yikes. For this entire party has to partake. Sorry! Talk soon!

And once you’ve assembled your perfect group of eager guests, there’s just something so damned celebratory about big-group dining, especially in an age when we’re dining out on a regular basis like never before. Chefs are famous for loving guests who want their food the way they intend it, which means they generally go all out for the large-format table. “The restaurant makes you feel special,” says Josephine Son, an advertising exec who describes herself as “that friend that everyone asks where to eat next.” Her favorite large-format experience so far has been “the whole roast pig at the Breslin. April makes a big show of it.”

At my Ssäm Bar duck gathering, the bird came out, and it was magnificent: a platter of confit-cooked fowl sliced into perfect disks, accompanied by ramekins of sweet-pungent hoisin and bright, bracing scallion-ginger sauce, house-made mooshoo-style chive pancakes and a heaping bowl of crunchy fried shallots, plus piles of fresh mint, basil and cilantro and tender leaves of Bibb lettuce for wrapping. We oohed. We aahed. We joked about hitting the gym post-feast, punctuating the punch line with exaggerated sips of a fowl-friendly chilled Gamay.

But then a funny thing happened. The duck? It faded into the background. No one was sizing it up. There was no one daring a neighbor to “give it a try.” No one was frenetically cutting their appetizer into six portions to dole out perfect mini-tastes to everyone at the table. “WHO WANTS TO TRY 17% OF MY OCTOPUS?” We were just eating—the same thing—and so our focus wasn’t on our plates. We were left to enjoy one another’s company. How refreshing is that?

MORE:

Secrets to a Successful Tasting Menu

Omakase Restaurants with 12 Seats or Under

11 Fine Restaurants with Communal Tables