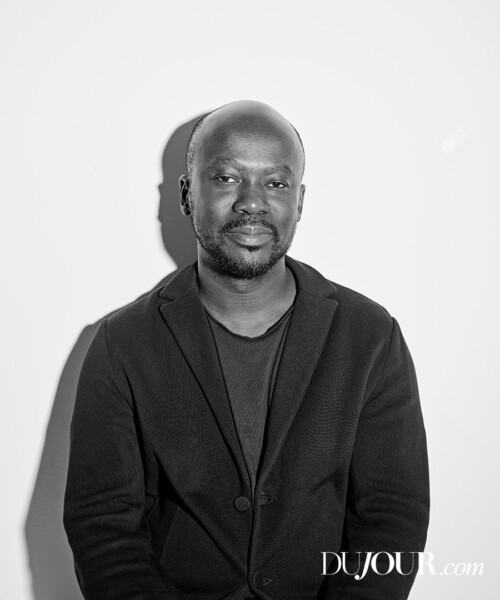

That populist ethos is the crux of Adjaye’s sensibility. “I want my projects to have an accessibility as well as an edifying and uplifting quality,” he says. A library, for instance, should both support and stimulate learning. He sets the bar high, unsatisfied with a structure that’s visually striking but a passive participant in the cityscape. “Architecture has such a profound effect on our collective psyches,” he says. “A public building affects vast communities. If it alienates certain sectors of the community for whatever reason, that’s a problem.”

That sense of social responsibility is rooted in his upbringing, fueled by the experience of his youngest brother, Emmanuel, who became disabled as a child. “Architecture wasn’t interesting to me until I found a purpose for it,” Adjaye explains. “And that came through my brother, observing how, before disability laws appeared in the ’80s, architecture segregated people.” The discipline became intriguing once Adjaye saw it as a catalyst for empowerment. “It was about taking on the ‘big art’ of architecture and making it into a service.”

Adjaye thinks like an outsider because he is one, both culturally, as a sort of citizen of the world, and professionally. He was not one of those kids rearranging his bedroom furniture and dreaming of one day becoming an architect. “I actually wanted to be a pilot,” he explains. A fascination with fast planes led him to join the air cadets as a child; he flew gliders in his teens. He considered joining the military until his father talked him out of it. “I remember having an awful fight with him that I am now very grateful he won,” Adjaye says with a laugh. But even after turning his focus to more artistic pursuits, his path to the profession was indirect.

It was only after designing some small-scale interiors with his art-school pals that he returned to school—London’s prestigious Royal College of Art—for his master’s in architecture. The following year, in 1994, Adjaye partnered with a friend to launch their own practice, and in 2000 he went solo. He quickly made a name for himself designing homes for a who’s who of art-world luminaries, among them Chris Ofili, Lorna Simpson, Jake Chapman and power couple Amalia Dayan and Adam Lindemann. “The influence of art practice on David’s work is palpable,” notes the Art Institute’s Zoë Ryan. “All of his buildings—large or small—insist on being accommodated as objects that share the space with those who inhabit them.”

Adjaye claims that the most formative aspect of his design education was learned beyond the classroom. “I spent a lot of time going around the world experiencing great buildings firsthand,” he says. “Travel was a great teacher.” Of course, it’s one thing to see the sights and another to learn the true essence of a place. What sets Adjaye apart is his studious deep-dive into the local micro-culture of wherever he’s building. His work is contextually appropriate, but not in the sense that the materials or detailing riff on surrounding buildings or the regional style. Rather, his designs emerge from painstaking research into a place and its people.

Adjaye has structured his practice to allow for an unusually in-depth programming phase during which a designer gets acquainted with the client, its needs and the peculiarities of the site. A few years ago, Adjaye set up a special department dedicated specifically to assisting him with this research. Members of the four-person team are deliberately not architects. They are social scientists, geographers, humanities majors and business consultants, as in the case of the department’s head, Ashley Shaw Scott, Adjaye’s wife. The department collaborates on all of the firm’s projects, and does its own consulting work for clients like Habitat for Humanity and the EU.

That team has been instrumental as Adjaye’s attention turns increasingly toward Africa, a huge growth area as well as a major challenge for the firm. “Building is not a straightforward process there,” he explains. “There’s a culture of contractors saying, ‘These are the five things we can do, and that’s it.’ We don’t accept that there are only five ways of doing things, so we’re constantly having to invent.” It’s clear that Adjaye sees this as an exciting problem-solving exercise, and a weighty responsibility. “I think it’s essential that we are a part of the change in Africa, helping develop the infrastructure and the economy. Otherwise, the work won’t get critical; it will remain generic and banal.”

These days, Adjaye’s cross-continental journeying has slowed following the birth of his first child. “My poor kid,” he laments. “Two months in and he’s already made his first transatlantic flight.” Parental guilt aside, Adjaye is eager to keep up the pace, changing the world one building at a time. For now, however, the man who might be the world’s busiest architect says what he’s most interested in is some shut-eye. “Sleep,” he says, “would be good.”