The South African-born choreographer Dada Masilo works with the sort of classic material—Carmen, Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake—that nearly everyone has heard of. But it’s what she does with the dances that have made her an international sensation and caused no less than CNN to claim she, “unsettle[s] audiences with interpretations that turn gender and racial stereotypes on their heads.” Indeed, her production of Swan Lake—which lands in New York City beginning February 2—features traditional African music in addition to Tchaikovsky’s classic score and casts both Odile and Siegfried as men whose relationship draws disapproval from a bigoted society. On the occasion of a London production, The Guardian noted, “Dada Masilo‘s new version stands apart from so many others not only for the fresh and fast-paced style that comes with the addition of African dance, comic theatre and carnival, but for her wit and seriousness in handling the original ballet’s themes.”

Here, Masilo explains what draws her to classic ballets, how she goes about changing it and what her next project will be.

What about Swan Lake made it attractive to you?

Swan Lake was the first ballet that I saw when I started dancing and I fell completely in love with the tutus, with the music, with the stage. And, you know, I really wanted to dance the work. But my path didn’t lead me to become a ballet dancer, so I thought, why not make a contemporary dance version and see what I can change, how I can approach the story. I started off working with a friend of mine who was a dancer, and I had this idea of having a male Odile and a female Odette and having a gay Siegfried.

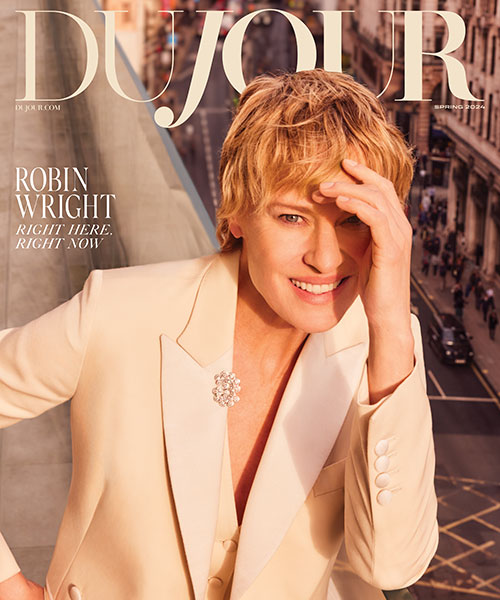

Dada Masilo’s “Swan Lake”; Photo by John Hogg

Is it purposefully transgressive? The production has certainly made waves.

I don’t approach it from a political point of view. I approached it from wanting to do something different with the story. There is also that misconception that all men who dance are gay, so I thought, OK, let’s had a gay Siegfried and see how that changes things. When people observed the work, it became this big political thing about homosexuality and homophobia, which was not really my intention. My intention was to just change the story up a little bit and play with things, to change some of the stereotypes and have men dancing on pointe as opposed to women. It’s just a different take.

You’ve said that the combination of ballet and African dance is difficult. What’s been the most taxing part of creating your Swan Lake?

Oh, definitely the movement vocabulary. If you look at African dance and classical ballet, they are the complete opposite of each other, so trying to get them to coexist was the biggest challenge. It was the most significant challenge for the dancers as well because we normally do the contemporary dance or classical ballet or fusion of classical ballet and contemporary dance, but never of classical ballet and African dance. To shift from the gracefulness of the classical to the really intricate ground movements of the African dance was a challenge for the body because it’s trying to do two things and sort of trying to defy itself.

How did you find a happy balance with two such different styles?

What I did was I listened to the music. I’m not using all of the Tchaikovsky, but I did choose the Tchaikovsky that was going enable me to do both the African and the classical dance. So, some of the Tchaikovsky pieces are completely classical and you can’t really break them down or put something like African dance into them. But some Tchaikovsky actually goes really well with African dance, so that was fun.

The production has at times been considered shocking. Did you anticipate that?

Absolutely not. I think that is the beauty of being an artist: You don’t work with expectations. I am just so grateful and so surprised that people are receiving the work so well and that they are being moved by it. I think that that’s the most important thing, to share with the audience and to just open up conversations about the issues that the work is dealing with.

Now that Swan Lake is chugging along, is there something you’re hoping to take on next?

I have three projects ahead that I want to do. I started working on The Rite of Spring late last year, and I am learning a new traditional dance from my homeland, which I’ve never done before. I am trying to learn that and tackle Stravinsky atonce, which is quite difficult. I made a Romeo and Juliet in 2008 that I want to rework now and see what changes I can make and how I can strengthen it. And I would also like to do a Giselle.

Do you go into these projects, say wanting to do a Giselle, thinking about how you want to turn it on its ear?

No, it definitely comes to me as I am working. For me, the starting point is the music. I really love music and that is what really inspires me to create. And so I will just, because there’s the theme, I’ll really love a given piece and that will be the reason I want to see if I can create something new out of it.

Main image by John Hogg