One million species of plants and animals are heading toward annihilation, and it’s our fault,” said the New York Times in May of a sobering United Nations report that states these species risk extinction by midcentury, due to the unprecedented—and accelerating—pace of habitat loss incurred by human activity. “How can we possibly live with that truth?”

Fortunately, it turns out not everyone is willing to concede to doom just yet. Groups that have long known the importance of biodiversity to our planet’s health are in fact working tirelessly to preserve and strengthen threatened species worldwide, with some inspiring results.

In New Zealand, home to more than 90 bird species that live nowhere else on earth, everyone has heard of the fuzzy and flightless Kiwi. But two other species, the stilt-walking Kakī and the rotund and playful parrot known as the Kākāpō, have needed a helping human hand after habitat destruction and the introduction of non-native predators, such as cats, rats, possums, and stoats, have decimated their populations.

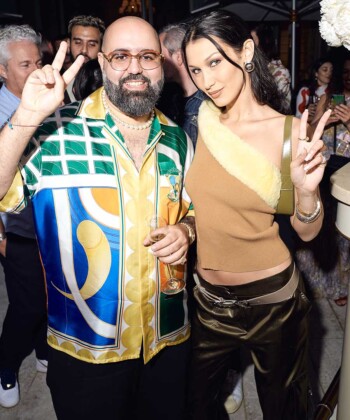

A pair of adult kaki in the Tasman Valley (photo: Liz Brown)

The New Zealand Department of Conservation and the Maori have partnered with the Austin, Texas–based organization Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC)—with additional support from the Sheth Sangreal Foundation—to help bring both the Kakī and the Kākāpō back from the brink of extinction.

Kākāpō, the world’s largest parrots, are green flightless birds that were once found across New Zealand and among the most common birds in the country. By the 1970s, biologists thought the species had been wiped out until, in 1977, two remaining populations—just 51 individuals—were discovered. In 1995, the Kākāpō Recovery Programme was established, and the tide turned for the beleaguered birds. The program’s success has been hard fought, with researchers and thousands of dedicated volunteers working to monitor the population and reduce threats by everything from feral cats to a lack of genetic diversity. The main Kākāpō population currently lives on three sanctuary islands, where the researchers and volunteers continue their steadfast efforts, often spending months at a time without connection to the outside world. Kākāpō breed only every two to four years, when rimu trees blossom into fruit. The Department of Conservation removes the eggs from their nests and puts them in incubators, leaving “smart eggs” in the nest and returning the chicks only after they’ve hatched. Each nest is fitted with sensors and cameras, and each bird is fit with a small radio transmitter backpack to monitor its movement, making Kākāpō one of the most intensively managed species in the world.

Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park (photo: Getty/Alexander S. James)

The results speak for themselves: 2018 was a banner breeding year for the species, with the hatching of 76 chicks, 60 of which are expected to reach adulthood. This is double the number hatched during the last breeding season, in 2016.

“The dedication of the volunteers and staff is incredible,” says Wes Sechrest, Ph.D., chief scientist and CEO of GWC. “The vision of the Department of Conservation, the Maori, and other local communities to restore this native species across its natural range is inspirational. We’re very lucky to have a chance to help recover and rewild these populations across New Zealand.”

Kakī, also known as Black Stilt, have distinct black plumage, long pink-red legs, and the unique ability to survive hurricane-force winds as well as temperatures ranging from more than 100 degrees to well below zero. Kakī, like the Kākāpō, were once widespread, residing in a unique system of braided rivers on New Zealand’s South Island. They are the world’s rarest wading bird, but their population of 132 is up from 1981, when there were just 23 known Kakī left in the world. The Kakī Recovery Programme’s success has been bulwarked by a six-bay aviary that provides suitable habitat for groups of young birds raised together from hatching. With the help of a contribution from the Sheth Sangreal Foundation, GWC is supporting the construction of a 10-bay aviary that will boost the program’s rearing capacity by some 60 birds each year.

GWC also supports the Te Manahuna Aoraki Project, which aims to restore 310,000 hectares of Kakī habitat in the mountain lands of Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park, and the lakes and iconic drylands of the upper Mackenzie Basin. This will help protect not only Kakī, but also at least 38 other endangered species, according to Simone Cleland, Department of Conservation biodiversity ranger and the Te Manahuna Aoraki Project manager. “GWC has helped put Kakī on the international stage,” Cleland says. “Their support has allowed us to increase the size of our ecosystem and species management from a few key sites to cover a massive landscape. What a dream! It’s a wonderful feeling knowing as a team we have worked so hard to save these birds and have given them a real chance of survival.”

May these uniquely charming birds—and the successful efforts on their behalf—continue to serve as the example we all need.