It’s January 2013, but unlike most people, California Attorney General Kamala Harris isn’t talking about the coming year. Instead, she’s speaking about the past: her election in 2010. That night, even many of her supporters doubted she’d win her bid to become California’s next A.G.; in fact, her opponent—Steve Cooley, the popular, moderate Republican district attorney of Los Angeles—declared victory a few hours after the polls closed.

But Harris, who’d been out to dinner with friends and family, was oblivious to the fact that she appeared to have lost. She recalls, “We got to headquarters, and my consultant said, ‘OK, speak to the folks and the news.’ I go out. People are looking at me and crying, and I thought, ‘This is so wonderful.’ I give my speech—this is what we stood for, this is why we ran—and I could feel the mood shifting.” Only after she walked away did the truth dawn on her. “Everyone was crying because they thought we had lost! I was the only one who didn’t think so!” And she laughs so hard I’m afraid she might choke.

In the end, Harris won, albeit by a margin so small—only 74,000 votes—that Cooley held out for three weeks before finally conceding. That close victory made her not just the top law enforcer in the most populous state in the U.S. but also one of the most powerful legal officials in the country. It was a job many believed that neither an African-American nor a woman would ever get, much less a liberal black woman who opposes the death penalty.

Every so often, a Northern California politician comes onto the scene who makes people in the area and nationwide go “Wow.” In recent years, San Francisco has had many: Nancy Pelosi, Dianne Feinstein, Gavin Newsom, Jerry Brown, and now Harris. Since she first got noticed in the mid-1990s, she’s been dazzling people with her political acumen, bold ideas and global-village glamour—and frustrating them with her relentless drive.

For these reasons, Harris, 48, is often compared to President Barack Obama, whom she’s known for almost a decade and for whose campaign she served as national co-chair in 2012. (Her brother-in-law, Tony West, holds the number-three spot in the Department of Justice.) She says, “[The president] and I have a relationship based on respect.” Harris was the only candidate for statewide office in the U.S. for whom Obama raised money during the 2010 cycle.

When I googled Harris’ name recently, the first thing to come up was the rumor that she would be tapped for the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 79 and ailing, may step down in the next year or two, and some think Obama will want to replace her with a trusted, younger, multicultural woman, someone with political skills and legal chops.

When I ask about the buzz, Harris gives one of those evasive answers that keep the gossip mills churning: “I am very focused on what is right in front of me. I love this job. You can have a direct impact of the lives of 40 million people.”

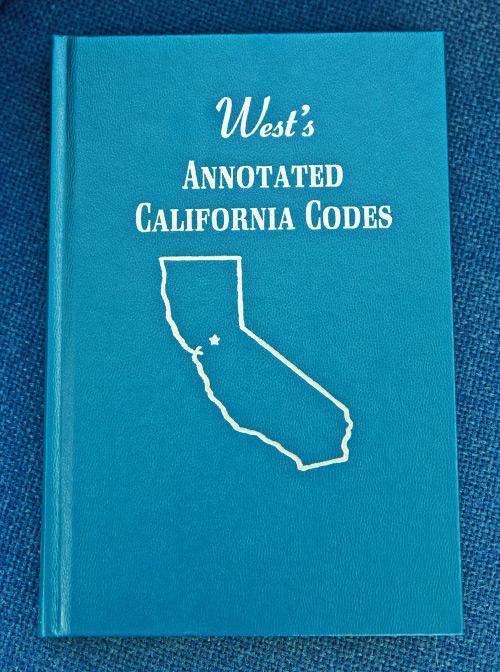

She showed that to be true with her first bold move as A.G. Shortly after taking office in 2011, Harris sicced her department on the big banks whose practices she held responsible for the housing crisis that had devastated California. (At one point, 9 of the 10 worst-hit metro areas in the U.S. were in the Golden State.) The banks weren’t amused. They were negotiating with 50 states and seemed likely to get a deal—paying only $2 billion to $4 billion to California in compensation and receiving immunity from all future inquiries and suits—that was less a slap on the wrist than a brush with a feather.

Harris was outraged. “One of the things I love about holding statewide office is that we are more nimble [than the feds],” she says. “And because the buck stops with me, we don’t have to ask permission to do the things we do. If the voters don’t like it, they’ll let me know.”

In August 2011, she went to Washington, D.C., to meet with the banks. People familiar with the talks say their lawyers assumed that the novice A.G. must be a lightweight and that her loyalty to the president, who wanted a deal to shore up his re-election chances, would trump any reluctance she had.

“They didn’t know what they were getting into,” says Harris’ senior policy advisor Michael Troncoso with a laugh. “Kamala’s a trial lawyer. She’s negotiated I don’t know how many plea deals, and she has a saying: ‘Don’t take “no” till the fifth time.'” The meeting ended after an angry Harris declared, “I’m going to investigate everything. All of it. I have an obligation to my client, which is the state of California.” A few weeks later, she pulled out of the 50-state talks, and the gnashing of teeth could be heard from Wall Street to the White House.

Flash forward to February 2012. After a frenzy of negotiating, she announced a deal with the banks, including some $18 billion in compensation—with at least $12 billion of it guaranteed for Californians—and no immunity from future investigations or state lawsuits. Bottom line: If you underestimate Kamala Harris, you do so at your own risk.

“With Kamala, the sky really is the limit,” says her friend Mark Leno, the influential Sacramento lawmaker. As ethnic minorities become the majority in much of the country, Harris—the child of immigrants, half South Asian, half black—looks like the future. While Democrats try to wrest that future from Republicans whose hard-line ideas, especially in the criminal-justice area, have dominated the political agenda for many years, Harris has given them some of their most effective talking points.

Her optics don’t hurt, either. She’s beautiful and always gorgeously garbed. Her personality is no less appealing, though her huggy warmth can turn to cold steel in a flash. She’s also hyper-energetic, demanding and hands-on. In many ways, Harris sounds like her whirlwind of a mother, a Brahman from India who came to the U.S. in 1960 to study, married then divorced a Jamaican-born fellow grad student (he is now a professor emeritus in economics at Stanford) and went on to be a top research scientist. Shyamala Gopalan Harris (who died in 2009) exposed her two daughters not only to the era’s antiwar and feminist politics but also to the world beyond their modest Berkeley neighborhood. Kamala, a couple of years older than sister Maya, was hard-working and a perfectionist, with a heart that bled for crime victims. Everyone expected her to be a civil rights or defense attorney. Harris, though, realized that prosecutors held the cards.

She got her undergraduate degree from Howard University and a JD from Hastings College of Law. She worked in the D.A.’s office in Alameda County for eight years and then in the San Francisco D.A.’s office. Because she wasn’t part of any existing political machine, she had to build her own coalitions to win a cutthroat race for San Francisco district attorney in 2003. In her eight years as D.A., she targeted areas, like the homicide prosecution rate, that she knew she’d be judged on (which earned her criticism as an ambitious climber who was always looking several steps ahead in her career). She also made some serious mistakes. Her quick declaration that she would not seek the death penalty for the accused killer of a young police officer earned her the wrath of cops statewide, and when wrongdoing was uncovered in the city police lab, her office compounded the problem by dragging its feet.

In 2010, she was seen as far from a shoo-in to become attorney general, especially since she’d be facing off against the well-liked Steve Cooley. “Some people said to me, ‘Don’t go there because they won’t vote for you.'” she recalls. “But I said, ‘Everything and everybody is on the table.'”

In general, the drumbeat of news about her department’s accomplishments has been steady and mostly positive. Harris, who oversees 1,100 lawyers, is proud of the action her office has taken to clear up its backlog of thousands of untested rape cases, and she thinks her efforts promoting use of a database to enforce state laws banning felons, spousal abusers and people with mental-health issues from possessing firearms could be a national model. She also worked with the major online platforms to hammer out a sweeping new mobile-app privacy policy.

The next year could be more productive. Since last November, when voters elected Democratic supermajorities in both houses of the Legislature and signaled their willingness to significantly increase taxes for the first time in 35 years, there’s been a palpable optimism in the air that lawmakers can partner with Harris’ office to pass progressive legislation—on the environment and gun safety, for instance.

Still, there is one big potential danger. Forced into a corner by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2011 that extreme overcrowding in California prisons constituted “cruel and unusual punishment,” Governor Jerry Brown has implemented “realignment”—moving tens of thousands of inmates convicted of less serious crimes out of state prisons and into county and local jails or even back on the streets. Budget cuts have left police departments understaffed and overwhelmed, and there have been few additional funds to help local jurisdictions pay for the influx of prisoners. Already there are anecdotal reports that crime in some areas is on the rise.

Realignment is an easy target, but it’s Governor Brown’s policy. Why would Harris be the scapegoat? Because as A.G., she is the person Californians associate with criminal justice, and she’s made her name touting similar policies. As D.A. and as A.G., she’s rejected the hard-line ideas that have nearly bankrupted California’s criminal-justice system and led to high recidivism rates (65 percent of the state’s ex-inmates will re-offend within three years of release). One of her pet programs in San Francisco, “Back on Track,” aimed to keep low-level drug offenders out of jail by providing them with services (everything from GED coaching to child care to gym memberships) and entry-level jobs. The program was successful enough that Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a similar one into state law in 2009.

Harris is aware of realignment’s possible impact on her career. “I have no doubt—because this is what innovation involves—there will probably be glitches. This is a whole new way of doing business.” She adds: “The fear that every law-enforcement leader has is that if you do something different”—like not locking up someone who committed a petty theft—”you’re taking a risk that the person will go out and kill a baby, and everyone will say, ‘What were you doing?!'” (Harris knows this from experience: In 2008, the D.A.’s office didn’t prosecute an undocumented immigrant/gangbanger for lack of evidence, and three months later, he was involved in the killing of three innocent members of the same family.)

Should realignment end up succeeding, though, no California politician is likely to benefit more than Harris. Many see her running for governor when Brown is termed out in 2018 or perhaps heading to Washington. It’s clear, however, that she’ll be making her own decision about where she’s going next, and she won’t be put off by naysayers. As she puts it, “Don’t tell me ‘no.’ That’s a bad and wrong thing to say to me. I eat ‘no’ for breakfast.”