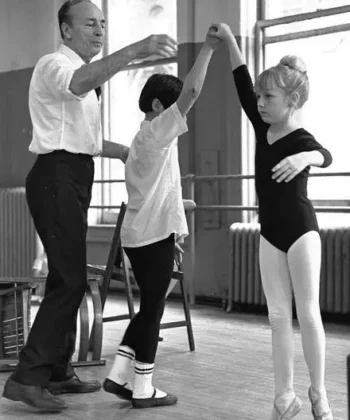

Keith McNally is the founder of Balthazar Restaurant, Balthazar Bakery, Pastis, Minetta Tavern, Minetta Tavern DC, Pravda, Schiller’s Liquor Bar, Morandi, Cherche Midi, Lucky Strike, Nell’s, Café Luxembourg and the Odeon. The British-born New Yorker is also the co-author of The Balthazar Cookbook and Schiller’s Liquor Bar Cocktail Collection and the writer and director of two feature films, End of the Night and Far from Berlin. In his new memoir, I Regret Almost Everything, McNally takes us on a journey through his remarkable life, from his working-class roots in London’s gritty East End of the 1950s to his current status as one of New York City’s leading restaurateurs and icons. Along the way, McNally tells us about the angst of being a child actor, his lack of insights from traveling overland to Kathmandu at age 19, the instability of his two marriages and family relationships, his 1980s rise to fame with The Odeon and Nell’s, his time spent writing and directing two films, his devastating stroke in 2016 and his recent Instagram notoriety. In the below excerpt, McNally remembers the opening of Balthazar almost 30 years ago in SoHo.

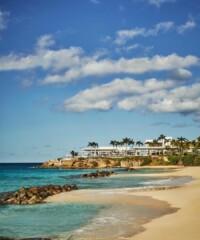

Balthazar opened to the public in April 1997. The impact was staggering. It was a restaurant hurricane that caused a sensation in the city’s nightlife. From day one, every seat was full. On the fourth night, we had three hundred people on Balthazar’s wait list for dinner. Vogue editor Anna Wintour ate there five nights in a row the first week. After six weeks, New York magazine published a double-page spread of Balthazar’s dining room with the positions and numbers of famous New Yorkers’ favorite tables. (Most of these celebrities hadn’t even been there.)

After several months, I decided to open Balthazar for breakfast, which the New York Post announced the day before. At seven thirty that first morning, we had a hundred customers waiting outside. I let them eat for free. In fact, I let all three hundred breakfast customers eat for free that first morning. The public and press response to Balthazar was stimulating for the floor staff but a nightmare for the kitchen. Chefs Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson were often angry and argued that in cooking hundreds of meals every day, we were risking the food’s quality. They were right, of course. But when you’re driving an Aston Martin for the first time, it’s difficult to think about the passengers in the back seat. Toward the end of a nine-hundred-cover brunch, I’d see Nasr scowling by the kitchen door, counting the number of customers still waiting for tables. Those were hair-raising days. I’m just thankful Nasr forced me to hire Hanson. Without a second chef, Balthazar would never have survived its first year.

The day after I opened Balthazar, someone had the gall to ask me, “So, what’s next?” Curiously, the number of people asking this question doubles with each new restaurant. Why is it increasingly more difficult for people to savor the moment? I’ve noticed that during TV coverage of an exciting sports event, the commentator will interrupt the action with news of an even more exciting one in two hours’ time. It’s like talking about your next baby when delivering your first one. The future isn’t always more exciting. Why must we always resort to hyperbole to retain people’s interest? I’m going to throttle the next person who asks me, “So, what’s next?”

A month after opening the restaurant, I was sitting outside Balthazar feeling quite pleased with myself, when I overheard two women talking disparagingly about the food. Crushed, I introduced myself and surprised the two women by offering them a free dinner if they’d agree to give Balthazar a second chance. They returned a week later and ordered a full meal, including wine and dessert. After they’d wiped their plates clean, I unctuously approached their table, preparing to luxuriate in their compliments, when the shorter of the two piped up: “Thank you for dinner, Mr. McNally, but to be honest, we don’t like the food any more than the last time. If anything, less so.”

A few years after Balthazar opened, a table of four Wall Street traders began their evening by ordering the restaurant’s most expensive wine: a two-thousand-dollar bottle of Château Mouton Rothschild Premier Cru. Following procedure, the floor manager transferred the thirty-year-old Bordeaux into a decanter at a waiter’s station. At the same time, a young couple on their first visit to the restaurant ordered our cheapest red wine, an eighteen-dollar bottle of pinot noir. Seeing the Mouton Rothschild being decanted at the table opposite, the couple asked if their wine could also be decanted. Though it was an odd request for such an inexpensive wine, the manager agreed, and minutes later these two radically different wines sat in identical decanters on the same shelf above the waiter’s station. What happened next was every restaurateur’s nightmare.

Confusing the two decanters, the manager served the cheap wine to the four traders. The table’s host, who considered himself a connoisseur, sniffed and tasted the eighteen-dollar bottle of pinot noir and burst into raptures about its “balance.” His three companions followed suit, praising the wine’s “tannin content” to the skies. Meanwhile, the young couple who’d ordered the cheap pinot noir were inadvertently served the Château Mouton Rothschild. Taking their first sips, they jokingly pretended to be drinking a very expensive bottle and parodied the mannerisms of the wine snobs at the table opposite.

Five minutes later, the two managers realized their error. Horrified and unsure of how to proceed, they called me at home. I rushed to Balthazar. Having never been comfortable in all-male company, I found it hard to identify with these four Wall Street traders sitting at table 62. As I watched them self-importantly drink what they imagined was a two-thousand-dollar Château Mouton Rothschild, I deplored my own profession—but who was I to criticize customers who were in the process of being deceived? Though their behavior appalled me, these four businessmen had, in good faith, bought a two-thousand-dollar bottle of wine and received an eighteen-dollar one instead. They’d been swindled. I didn’t know what to do. If I were honest and told them the wine they were eulogizing was a cheap bottle of pinot noir, I’d embarrass them to no end and expose their true knowledge of wine.

The alternative was to say nothing and allow them to remain in blissful ignorance, which would also save me two thousand dollars by not having to replace the pinot noir with a second bottle of Mouton Rothschild. I ended up doing what I rarely do in this business: I told the truth. When I explained the mix-up to the four men, the host quickly responded, “I knew this wasn’t a Mouton Rothschild!” and his three comrades obsequiously agreed. I then told the young couple about the mistake, but let them keep drinking the real bottle of Mouton Rothschild. They were ecstatic, comparing it to a bank making an error in their favor. However, in this case it wasn’t the bank that was down two thousand dollars, it was me. Knowing they were drinking expensive wine for real, they switched from acting out drinking expensive wine in jest to acting out in earnest. Which was a pity in ways I couldn’t explain.

Both parties left Balthazar happy that night, but the younger of the two left happier. After spending over forty years in the business, I still don’t know what makes a restaurant successful. I know what makes one successful for me though. It’s a restaurant that’s conducive to engagement, where the customer can fully connect with their dinner companion. I’d rather eat mediocre food in an all-night diner and forge a connection with the person I’m with than eat in a four-star restaurant and have nothing to say to my companion.

The saddest sight in the world to me is seeing a married couple sitting opposite each other in silence. It reminds me of my parents. A far more pleasing sight is a customer happily eating alone—preferably reading a novel between courses (or eating between pages). To help make single diners feel comfortable eating alone, I always send a glass of champagne on the house. Always.

Excerpted from I Regret Almost Everything by Keith McNally. Copyright © 2025 by Keith McNally. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.