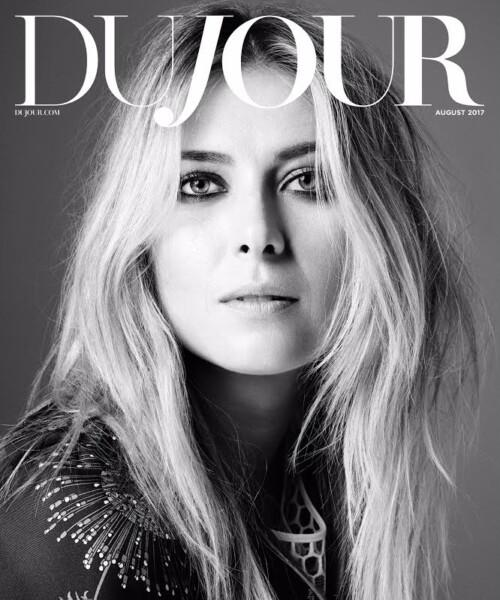

Most thirty-somethings haven’t lived quite enough life to fill a memoir. Of course, Maria Sharapova, who turned 30 this year, is not like most thirty-somethings; she is superhuman. This is supported not only by her relentless tennis game but her almost Marvel-ian origin story involving a nuclear disaster, a sojourn from Siberia, and a supernaturally strong swing – all touched on in her forthcoming memoir, Unstoppable, an apt title given the setbacks Sharapova has faced in the past year and the rote determination with which she’s faced them.

“When I got the book deal in 2015,” says Sharapova, “I was in my late 20s and I don’t think I was ready to write it. But whenever I answered questions about how I got here, [people] would say ‘Oh my goodness that sounds like a movie.’” Sharapova was born in Nyagan, Siberia in 1987, where her parents had recently moved following the Chernobyl disaster a year earlier. “My parents were living in Belarus at the time so my mother was very close to all the radiation while being pregnant with me,” says Sharapova. At the behest of her grandparents, Sharapova, her mother Yelena and father Yuri moved north to Siberia, which, says Sharapova, was only somewhat more kid-friendly. “I was born in an industrial little city that didn’t have much life and was just not a great environment to raise a child in,” she says.

From there, the family migrated to the resort town of Sochi, where the flaxen-haired four-year-old might have eased into the normalcy of childhood. Instead, Yuri, a burgeoning tennis enthusiast himself, began carting Sharapova to the local courts where they met Maria’s first coach, a vodka-swilling local legend, and where the child practiced on an adult-sized racket. “We had to chop it down because it was so big,” says Sharapova. But the clumsy racket induced quick muscle growth – an emblem of Sharapova’s ability to adapt to challenges and use friction to her advantage.

Indeed, despite Sharapova’s athletic talents, her upbringing in Sochi was not that of a golden child, but one in which Russia’s post-Soviet gruffness had yet to thaw – as illustrated by one traumatic trip to the eye doctor. “I had something painful on my eyelid that had to be removed,” says Sharapova. “And the first thing [the doctor] said to me was, ‘How could you possibly not have your hair tied back?’ I was like, ‘Uhh,’ and immediately locked up and wasn’t willing to share any emotion with her. So even though they had to do the procedure without anesthesia, I didn’t cry until I got home.”

But there were also glimmers of inspiration. On a trip to a tennis clinic in Moscow, the father-daughter duo ran into Martina Navratilova, who, after seeing the young Sharapova play, encouraged Yuri to relocate his family to America. Shortly thereafter, Yuri and Maria left Russia, and Maria’s mother behind (Yelena would follow when Maria was nine) and one 15-hour-flight later, they were at the doorstep of the famed Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy – an incubator of talents such as the Williams sisters and fellow Russian export Anna Kournikova.

From the outset, Sharapova and Kournikova’s superficial similarities (Russian, blonde, plays tennis, end of list) attracted frustrating comparisons. Sharapova even had to wear Kournikova’s hand-me-downs at the tennis academy. “I don’t know how but I would end up with a lot of her old clothes,” says Sharapova. “A lot of prints and animal prints and glitter and definitely not things I would’ve chosen to wear when I was 8 or 9 years old [laughs] but I didn’t have a choice.”

But if Kournikova was a minor foe, Serena Williams was the final boss. Since Sharapova’s training days, Williams has held an almost mythological status. “[The first time] I watched her at the academy, years of my life rolled by right in front of me,” Sharapova says. Snap to nearly a decade later, Williams and Sharapova were facing off in the 2004 Wimbledon Championships — 17-year-old Sharapova’s first big slam. “Serena was the one who was expected to win the match,” she says. To everyone’s surprise, Sharapova beat Williams 4-6, 6-2, 6-4 – everyone but Sharapova herself, that is. “I was like a silly teenager; if it was there for me to take, why wouldn’t I do everything that I can to take it? And I think from that point on, from that victory that I had against her, our rivalry began.”

That breakout season catapulted Sharapova to level of fame and wealth unheard of in Sochi – but even as a teen, she was not naïve. “In a way, the academy in Florida is very much a factory. You have the investors and the kids who produce the work,” Sharapova says. “So I think I understood the business side from a very young age. But in terms of my own success and what it would bring me… I don’t think you can really prepare for that.”

Sharapova would subsequently win 35 singles titles including five Grand Slams, and, while repeating her defeat of Serena proved difficult, would become the highest paid female athlete for 11 years running. In 2016, Forbes estimated that Sharapova had earned $285 million during her career. Nearing her 30th birthday, Sharapova was thinking less about tennis and more about retirement.

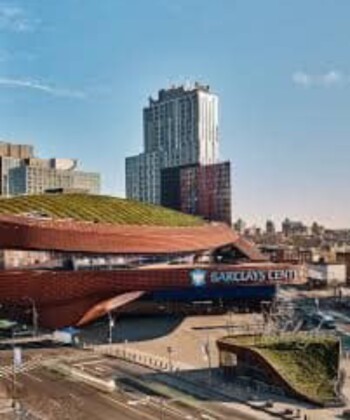

She took some time off — but Sharapova was hardly sitting back and eating bonbons. In fact, she was selling them. She launched her brand of chocolate bars, Sugarpova, in 2016, and by the end of 2018, it will be sold in an estimated 50,000 locations. In addition to working on her book, Sharapova took a two-week course as Harvard Business School and interned at the NBA.

Sharapova has also stopped thinking about retirement. “I never envisioned still competing past 30 years old when I was a young girl. But there are so many years ahead of me and I envision a few more years [of playing],” she says. “Unlike when I was young, I think the mystery and not knowing what will happen is interesting. It’s okay rather than seeming a little scary.”