“People always say to me, ‘Why don’t you get along with critics?'” Lou Reed told me one night last year. “I tell them, ‘I get along fine with Anthony DeCurtis.’ Shuts them right up.” We were sitting in the dining room in the Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania, where I teach creative writing. I’d brought Lou down to do an interview with me in front of fifty invited guests and to have dinner with a dozen or so students, faculty, musicians and local media luminaries. Like so many things with Lou, it was touch-and-go until the very end. “We could just not do this,” he’d said to me the day before as we sparred over the logistics of his visit. It wasn’t a suggestion, it was a threat.

But, in the end, Lou showed up. His one demand—I’m not kidding—was for kielbasa to help with his diabetes. He blew off the reception he’d agreed to attend before the interview and we sat in an office munching on delectables from the famed DiBruno Brothers gourmet shop in Philadelphia. I could hear the reception going on outside as we sat and chatted, perfectly amiably, as if neither of us had a worry in the world – or anything particular to do that evening. Lou got so lost in the food—”This is the best prosciutto I’ve ever tasted!”—that I hated to interrupt him so that we could go out and begin the interview. When things were going well with Lou, it was always a good idea not to break the flow. Finally, as casually as I could, I indicated that it was time for us to do our talk, and we got up to leave the room.

When we emerged I could feel the audience’s tense energy. Lou, of course, seemed impervious. It was clear that people were worried about whether or not he would appear. But we had a great conversation and afterwards Lou chatted with everyone who approached him, signed autographs and stayed for dinner. Most important, everyone there got his or her Lou Reed story, a genre that is nearly as legendary as the artist himself.

As for me, I got my compliment. I’d gotten to know Lou from writing about him in Rolling Stone and elsewhere, and over the course of 15 years we’d regularly run into each other in New York—at clubs and concerts, at restaurants and parties. I always felt that one of the reasons that Lou and I got along well was that we met socially before we ever had to tangle as artist and critic. In June of 1995 I got stuck at the airport in Cleveland, where I had gone to cover the all-star concert celebrating the opening of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Backed by Soul Asylum, Lou had turned in a roaring version of “Sweet Jane” as part of that show. My flight back to New York was delayed for hours and I was settling in for the wait when I ran into a record company friend, who introduced me to Lou and Laurie Anderson. There’s nothing like an interminable flight delay to grease the gears of socialization.

“You reviewed New York for Rolling Stone, right?” Reed asked, referring to his classic 1989 album.

“Right.”

“How many stars did you give it?”

“Four.”

“Shoulda been five,” he said, but he was smiling. The ice had been broken.

So we sat and chatted in the airport lounge. The subject of the Hall of Fame’s list of the “500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll” came up, and Lou asked if “Walk on the Wild Side” was on it. It was—the only one of his songs to make the list. He asked about some others, but seemed pleased to at least be represented. Then, in a truly sweet gesture, he asked if Laurie‘s “O Superman” had been included. It had not been, but I got a sense at that moment of how important she was to him. He wanted to make it clear that he saw her work as significant, and he didn’t want to make the moment all about him.

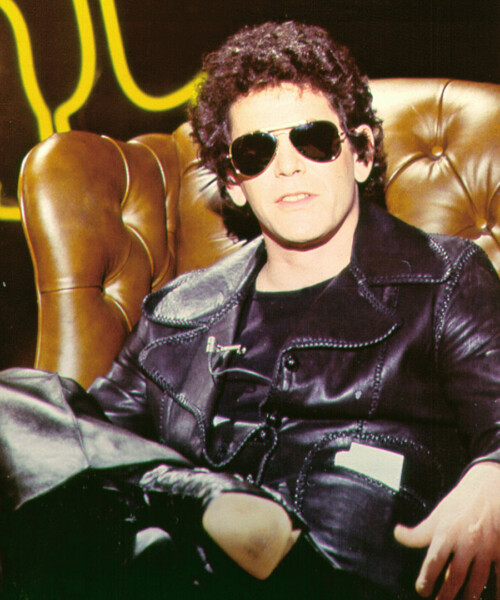

Though I subsequently interviewed Lou a half dozen times or more for stories and at public events, I recall these more casual moments with great affection. I talked with him at length about Brian Wilson, whom he greatly admired, at a party for Amnesty International. Another time I ran into him outside Trattoria dell Arte on Seventh Avenue when he and Laurie were heading to Carnegie Hall to see the Cuban musicians who had been part of the Buena Vista Social Club phenomenon. It was a warm summer night and Lou, quite uncharacteristically, was wearing a light-colored short-sleeved shirt. He was in his late fifties at the time, and his hair was graying and in the fading sunlight I could see the lines of aging on his face and neck. He looked vulnerable, human. Rather than the daunting, leather-clad, sunglassed figure of Lou Reed, King of the demimonde, he looked like the man he had in a sense become: an aging Jewish New Yorker out for a night of entertainment with his smart, attractive girlfriend.

He also seemed to be in a terrific mood. He was excited to see the show and asked if I was going. When I explained that I hadn’t arranged for tickets, he half-jokingly asked, “Do you think Laurie and I could get you in as some kind of”—he hesitated in order to come up with the exact right phrase—”celebrity perk?” I laughed, but was touched nonetheless.

Encountering him around the city that way always made me proud to be, like him, a New York native. An artist of incalculable significance, Lou Reed was also, as one of his songs put it, the ultimate “NYC Man,” as inextricable a part of the city as, say, the Twin Towers. Now he and they are gone and the city still stands, however much diminished.

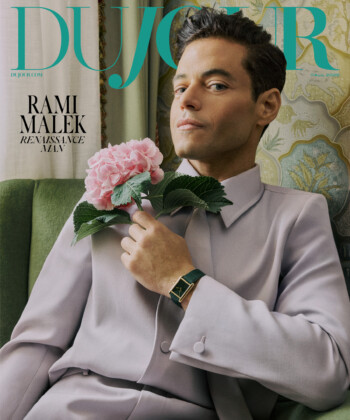

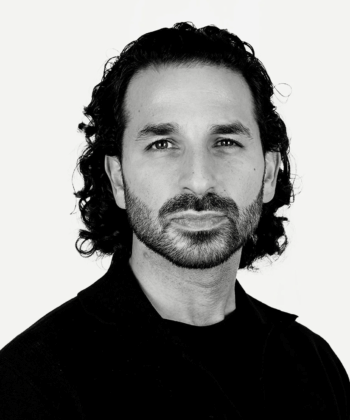

DuJour contributor Anthony DeCurtis is writing a biography of Lou Reed for Little, Brown.

MORE:

A Tribute to Linda Ronstadt by Rufus Wainwright

Robert DeNiro is Talking to You

Gloria Esteban Goes Back to the Standards