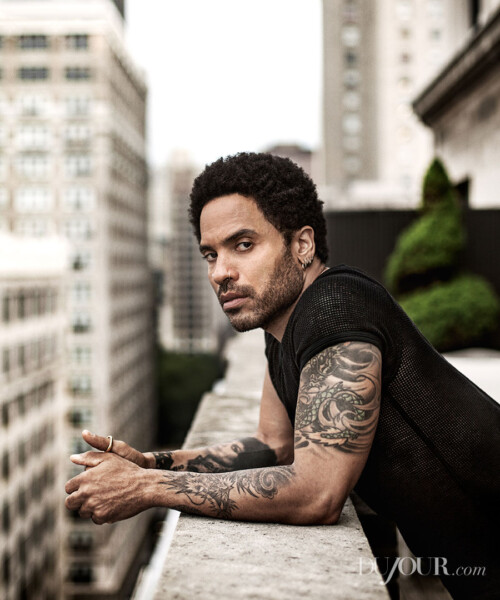

In the opening moments of the music video for “The Chamber,” the first single off Lenny Kravitz’s new album, Strut, the screen is splashed with a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche. “The true man wants two things,” it reads, “danger and play.” But for Kravitz, who’s got 25 awards-strewn years in the music industry behind him as well as a role in the $400 million and growing Hunger Games franchise, there seems to be more out there than the two options Nietzsche presents. This man wants to be heard.

“I don’t tend to think about what people are going to get from my work,” Kravitz says on a static-muffled phone call from a European tour. “I really just think about expressing myself. But then, you meet people and they say this or that song meant something to me, or when my child was being born I played this album, or when my mother died we played this song at the funeral. When you get heavy stuff like that, it’s beautiful. You become a part of people’s lives without being aware of it.”

If Kravitz isn’t aware of how he’s become part of people’s lives—a chiseled, bohemian, guitar-wielding patch of our cultural wallpaper—he might be the only one. Since his 1990 debut Let Love Rule was released, Kravitz released five platinum albums, dropped landmark songs including “Fly Away,” “Are You Gonna Go My Way” and “American Woman,” has appeared in everything from Zoolander to The Simpsons and Precious and, in October, will release an eponymous coffee table book celebrating his role as an internationally admired clotheshorse.

According to Kravitz, the element all of this work has in common is that it appeals to his visual sense—even the aspects which can’t been seen by the naked eye.

“When I hear music, it’s visual; I see things,” he says. “Most of it is abstract, but sound fires vision. It also happens when I enter an empty space and automatically envision where things should go based upon the guidelines or the project I’m working with. It’s something instinctual.”

In the case of Strut, Kravitz’s 10th album, the instinct struck while he was already at work on another project: playing the role of the stylist Cinna in The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.

“I had no idea I was going to make an album,” Kravitz says. “I was filming Catching Fire, I was not making an album, and I knew that I had two choices: Keep doing what I was doing or do what the creative spirit was telling me. So, I chose to do the latter, and it became this album.”

Kravitz says he’s startled by some of the songs he wrote—“I was surprised by the tone and the sound of ‘The Chamber,’ but when that happens I just go with it,” he says—but that the album ended up being just the thing he needed to do.

“I’m glad I stayed disciplined,” he says. “I would work at night and do the songs by day. I was quite burned out, but it was very fulfilling.”

Luckily when Kravitz gets exhausted by one endeavor, he’s got plenty of other projects to feel passionate about. His book with Rizzoli, for example, provided the opportunity to look back on 25 years of (often shirtless, sometimes rather experimental) style and gave Kravitz, himself a photographer who’s working on creating a camera for Leica, a chance to take a lesson from the big-name shutterbugs (Patrick Demarchelier, Ellen von Unwerth and Anton Corbijn to name a few) who have shot him.

“There were so many photographs, so I was seeing all this stuff and figuring out what worked for the book,” he says. Also, after more than two decades of photography it’s interesting to see how many versions of myself there have been; I didn’t even realize it.”

And does Kravitz, who famously sports leather pants, boas and any manner of ostentatious finery, have any sartorial regrets?

“I was all over the place,” he says with a laugh. “I think my style is more developed now, I think it’s more refined.”

That’s something that’s true for him across the board. Kravitz says what has stayed the same is his need to share what he’s feeling, whether it’s through music, performance, design or fashion.

“I’m just expressing myself, and often times somebody else will have a bond with that,” he says. “That’s the beauty of art and music.”