“Everybody thought this was the worst idea for a movie, because you don’t want to watch somebody else on drugs… and to a large extent I thought maybe they were right. But I just kind of wanted to try it.”

Gregory Kohn—the director of Northeast and now Come Down Molly, which premiered last week at the Tribeca Film Festival—did try it. He tried mushrooms, had a great time of it, and then tried making a movie about what it’s like to be on mushrooms. Come Down Molly centers on a young-ish woman, Molly, who is suffocating under the thick blanket of new motherhood. She tells her disapproving husband and sister she needs to get away, and drives to the country home of an old high school friend who is hosting a group of guys she used to be close with, but hasn’t seen in years. They take mushrooms and drift through the countryside for an afternoon, pausing for reveries and soliloquies—a string of recognizable musings from the drug-enlightened mind—for about an hour of the 80-minute film.

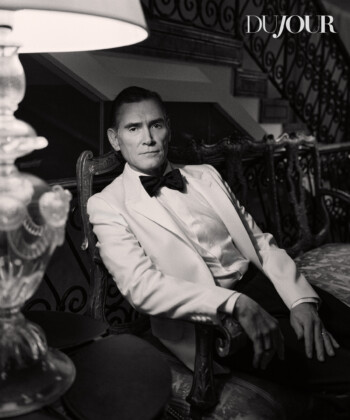

Gregory Kohn talking to Eleonore Hendricks on set

While it may require some patience, the film isn’t without its virtues. The cinematography is striking and atmospheric. It’s very well acted—much thanks to Eleonore Hendricks’ character Molly—and often improvised to charming and relatable effect. Kohn says much of the movie was impromptu: he loosed the actors into a field, letting them frolic and riff for days as the cameras rolled. “There’s a line in the movie where John says, ‘I wish this was a blanket tree,’ and Jason is like, ‘You mean made of blankets?’ There’s just no way I could write that.”

Kohn says he tried to keep the film as unscripted as possible. “It’s really hard for me to watch most movies or TV. I can’t watch them because I get frustrated to no end when people aren’t talking the way that real people talk. If I’m watching a WB show and a woman walks into the room with her hair curled up like she’s just gone to the prom, but she’s in high school and it looks like she just spent two hours getting her hair done, I can’t stand it. It’s fun for everybody else, but for me it’s a frustration.”

For this reason, at the end of Come Down Molly, Molly returns to her family seeming only slightly happier to have them. “It was really important that there was no catharsis,” Kohn says. “There was no message—she wasn’t given any light at the end of the tunnel.”