It’s late December, and in seven days Michael Bloomberg will end his term as mayor of New York City. As one of his last daily appointments, DuJour has brought him together with Christo, the architect of what might well be the artistic high point of his time in office, The Gates, the draping of Manhattan’s Central Park with thousands of bright orange panels.

“I thought this guy next to me was just a genius,” says Bloomberg, a longtime art enthusiast. “It was a wonderful trip together. We made a great couple.”

“This is something that is involved with chemistry,” agrees Christo. “If you’re missing that, you cannot decide to have public art. Otherwise, it’s propaganda.”

As a cadre of BlackBerrying staff members looks on, the mayor and the artist chat like old friends on a mezzanine above the City Hall bull pen. The two men’s connection is more than conversational: At this moment, they’re both preparing for the third acts in their lives and careers. One of Bloomberg’s plans is to help cities around the world develop their cultural institutions with the help of his nonprofit consultancy firm. As it happens, Christo could benefit from a bit of advocacy himself. The artist is wrapped in red tape.

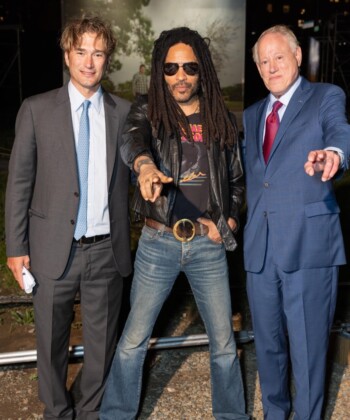

Christo at work on The Gates projects

A few weeks later, Christo is in his studio. The pioneer of public art, best known for swaddling coastlines, bridges and landmarks in great swathes of fabric, plunks two giant three-ring binders marked with U.S. government logos on a coffee table in front of a visitor. The binders contain a three-volume environmental impact statement.

“These are 4,000 pages,” he says, “written for the work of art that does not exist yet! No other artist in the world has so much written about his work that does not yet exist.”

Christo is 78 now and focused on two of his most ambitious works, which he acknowledges will be his last. They may not be built in his lifetime. Over the River—the reason for the 4,000-page environmental-impact study—would cover nearly six miles of the Arkansas River in Colorado with translucent silver waves of fabric. The Mastaba would stack 410,000 55-gallon oil barrels into a giant pyramid in Abu Dhabi, rising 492 feet, and would be the only permanent large-scale exhibition of Christo’s work. It would be his legacy.

Christo with a model of The Mastaba in Abu Dhabi. See more photos in the gallery above.

Today Christo is in his home base, a five-floor building in New York’s SoHo. This was a pioneer settlement when he and his flame-haired wife and artistic partner, Jeanne-Claude, bought the space in 1973—but today it’s more like living inside the Mall of America, near the roller coaster. A security guard sits in a garage on the first floor; the second has the vibe of a MoMA private exhibition room, with tan carpet, high white walls displaying sketches of The Mastaba and glass cases with Christo’s first sculptures. The scent of sandalwood wafts through the air.

“They’re two distinct periods,” says Christo of the approval process and the actual installation. “One is the software period, when the work only exists in my preparatory drawings and studies and the minds of people who try to help us and the minds of people who try to stop us. The hardware period is when we physically move to the space.”

Right now, Christo’s team is done with software. They’re waiting for the board of directors—the U.S. and U.A.E. governments—to get its act together.

The artist wears a blue-and-white striped shirt, jeans and sneakers and has a wiry shock of white hair left to its own devices. He has more than a little of a mad-professor affect, with a tendency to monologue (his response to a visitor’s first question verges on 20 unbroken minutes). “In the last 50 years, we realized 22 projects and failed to get permission for 37,” he says. He has been actively working on Over the River since the early 1990s. The Mastaba was conceived in the 1970s.

Christo’s works are admired, but they are not always beloved—their effect on the landscape has often been controversial, and their transience allows the debate to freeze in time. Many of his works have met with controversy and outright, repeated refusals. The wrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin resulted in three refusals by the government, hearings in Parliament and a press frenzy during which a German newspaper published a death threat sent in by a reader. Over the River has been opposed by citizen groups and led to the protracted environmental-impact study. Christo says he has paid $260,000 in rent to the government after getting approval for the project.

But there have been populist successes. Christo’s most notable recent public work is The Gates, 7,503 vinyl rectangular frames hung with orange fabric that drew millions of visitors to Central Park when it was on view for 16 days in February 2005. Michael Bloomberg, an undisputed fan, pushed the project through.

Christo’s The Gates

“This brought an enormous number of people, many times more than anybody thought it would,” says the former mayor. “It got us on the cover of every newspaper, magazine, TV program around the world. It built tourism. But I always thought that the real reason to do it was for the people of New York. People live here because they love a multicultural, exciting, intellectual environment. They like new things. They like the avant-garde. This project is the kind of thing that makes a city a city.”

The Gates was originally proposed in 1981 and rejected by Mayor Ed Koch’s administration three times, under pressure from community boards. “I have absolutely no idea why,” says Bloomberg. “Although I do think that it is difficult to imagine certain things. People who don’t like things, they’re the ones that really get up to yell and scream. People who like things tend to work quietly and get it done.”