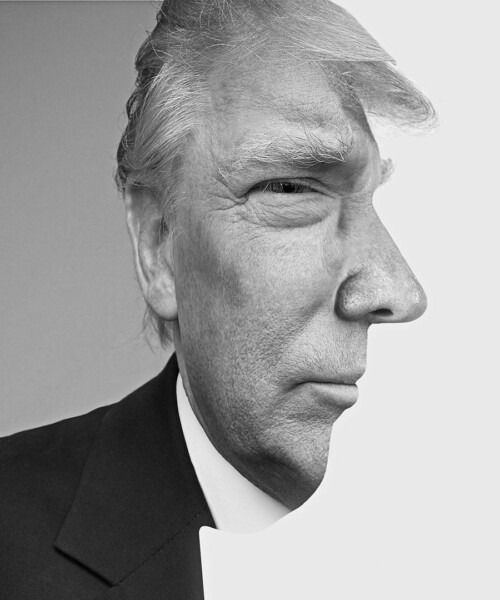

“It’s a funny thing to be loved for firing people…” mulls Donald Trump in his workplace aerie in Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and 56th Street. He’s talking about the success of his reality series The Apprentice, now in its 13th season on NBC. “You know I think I’m a very nice person. I help people. I love to help people…yet to me it’s very interesting and very sad that the show is number one, and [its catchphrase] is ‘You’re fired’ and viewers love me for it.”

For a fleeting moment the Donald purses his lips, puts his hands together as if in prayer and reflects. There’s a glimpse of someone else here. Someone I call “Second Donald,” the man in the shadows—and I’ve been able to see this Donald firsthand.

It’s the end of January, and the real estate titan and political pundit and I are having the latest of several conversations that we’ve shared since 2010. In person he’s tall, he’s formal—and he’s quieter than he comes across on-screen. Even his much-pilloried hairstyle and its color look subdued.

The phone buzzes in his office almost immediately; the caller is a banker from Florida. “Vincent, Vince…Vince…” The Donald is bouncing around. “What are you doing? You’re the greatest… Where are you in Florida nowadays, Vince? You know I just bought the Ritz-Carlton, Jupiter…and do you get to my course in Mar-a-Lago? No? Oh. That’s terrible. I bought Doral [in Miami] too…bought ’em all…I got like a monopoly…Could you call me next week? If I can help the bank I will…”

He puts the phone down and starts telling me about Vince.

“He’s the head of a big bank in Florida. Wants to know if he can do business with me…dying to do business with me, so he respects me…that’s why when you have a problem I can call them for you.”

Most people would hear this and write it off as typical Trump bombast. In the last few months, the Financial Times has mocked his verbiage as “trumptastic.” Another piece in The Atlantic described him as nothing more than a branding/marketing whiz, derided by the big banks as the “Paris Hilton of the business world.”

I have no idea who Vince is. I also cannot know if he really needs Trump’s help rather than vice versa, but here’s what I do know: There’s an altruistic streak beneath the bombastic veneer. Trump really does like helping people, and, contrary to allegations, he isn’t viewed as a milquetoast or Paris Hilton by Wall Street bankers. Far from it.

I know this as a result of research on my forthcoming book on the history of the most expensive piece of commercial real estate in America: the General Motors building, which Trump once owned. Some of the bankers at major Wall Street banks who have financed his deals over the years—and continue to do so—have talked to me for the book. Many of them say that he is a canny, wily negotiator not to be underestimated.

Further he called my bank on my behalf during a house sale in the middle of my divorce three years ago and he was effective. No one at the bank—perhaps the biggest bank in the U.S.—ever asked: “Donald who?”

His generosity was both enormous and (until now) under the radar—not a phrase usually associated with Donald Trump. At a frenzied press conference held at Trump Tower in early May, Trump announced he would be giving away money ($5,000 each to 10 people) as part of a promotion for his new partnership with crowdfunding website FundAnything.com. As for my own experience, Trump helped me for no very good reason other than he liked me, he’d liked my first book about the fall of Lehman Brothers and he saw me struggling. (His daughter, Ivanka, and others—friends, real estate peers, even another journalist—say he has done similar things for several people who work for him, including putting their kids through college.) After he called my bankers, they stopped hurting me. His brokers helped me find an apartment, and he invited my children and me to stay at Mar-a-Lago, his 20-acre private resort in Palm Beach, Florida. And he did all this without getting anything in return. This could be why I’m somewhat protective of him. I may be one of the few (OK, very few) journalists who feel sincerely empathetic for him when he says that he is misunderstood by the media and he can’t quite work out why. I have begun to see two men in him: Donald One, the impenetrable familiar caricature. And Donald Two who is, well, vulnerable.

“I have a much better relationship with the public than with the media,” he says. “Some of the media is great, professional, and some of it’s just dishonest,” he says, in particular singling out Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter, who served as my mentor for many years. (The two men have never liked each other.) Carter wrote about him in GQ magazine back in May 1984 for a themed issue on “Success.” “It was the worst article, but the cover [photograph] was great, so I put it up, you know?” he says, looking at it on the wall.

Right there you have the two Donalds, openly discussing the best and the worst in the same sentence. I see this contradiction in him quite often. Take for example his relationship to the topic of my book—the General Motors Building.

Trump loved the building when he owned it in a joint venture with the insurance firm Conseco from 1998 until around 2000, but he tells me that he doesn’t love talking about it. He wasn’t able to hang on to it after his partners went bankrupt. “This was the only deal I’ve made where I made a lot of money but I was disappointed in the deal. I really wanted the building,” he has told me bluntly. “I fixed [the building]; I made it great. I came up with the idea of the dome in front…and Steve Jobs got the credit for that, and that’s OK. Let him have the credit, he was incredible.”

Again, the two Donalds—one capable of giving credit, one eager to take it away. The truth lies somewhere in the middle. Steve Jobs’ vision was incredible. Apple turned the building into the most visited retailer in the world. But was Trump behind this? Not really. He did call the guy who ran the Cheesecake Factory and see if the chain would put in a restaurant shaped as a glass triangle. It never happened. But Harry Macklowe, the developer who bought the building in 2003, had a similar inspiration. Macklowe drew several shapes on a napkin at the Four Seasons Grill Room, got on a private jet and flew to see Jobs, and the idea of the cube turned into reality. But Donald doesn’t worry about details like this. They are unimportant when it comes to the bigger narrative of his life—and whether it captivates or repels you, the story of Trump is compelling.

Donald Trump with his real estate mogul father, Fred, at the Trump Plaza hotel, in 1988

Donald Trump with his real estate mogul father, Fred, at the Trump Plaza hotel, in 1988

Donald John Trump Sr. grew up rich but unsophisticated. His father, Fred, the successful New York City developer who began the family legacy in real estate, gave him an address book with powerful connections, but the family had yet to cross the river from Brooklyn. It was the young, brash Donald who made the move, driving around in his father’s Cadillac stretch limousine and famously appearing to be on the phone with all the governors, mayors and city planners of New York. No one knew whether he actually was or not. But he had chutzpah. He did a deal he couldn’t really afford (his father would have to help him) with the Pritzker family, which made him a co-owner of the Grand Hyatt New York Hotel. That set him up to buy the Trump Tower. With its ornate façade and a cascading waterfall, it also announced Trump’s style to the world. Trump had decided he would not do anything without a (literal) splash ever since, as a young man, he’d seen the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge open and watched the architect, Othmar Ammann, be ignored at the ceremony. He would never make the mistake of being quiet about what he did. What was the point?

Trump with contestants for Miss USA, which he also owns

Trump with contestants for Miss USA, which he also owns

Outwardly it looked like uncalibrated, careless flash. He dated models, marrying a Czech blonde, Ivana, in 1977, with whom he had three children, Donald Jr., Ivanka and Eric. He had a public brawl with New York City mayor Ed Koch over the West Side Yards. He bought three casinos in Atlantic City and developed a rivalry with Vegas developer Steve Wynn. He bought an airline, a boat, the Miss Universe pageant (which he still owns). He bought a football team, the New Jersey Generals, and wrote a book, Trump: The Art of the Deal.

Trump seemed unstoppable. A Jay Gatsby with bling, the gaudy symbol of the American dream. And like many men who peak, he overreached. He had bought the Plaza hotel when he didn’t know much about hotel management. Deep down, it would also emerge in a confession to a peer, he had no real passion for the casino business either. These things mattered when the market turned in the early ’90s. At the same time, Trump was undergoing an expensive divorce to Ivana so he could marry his then-girlfriend Marla Maples.

He had to sell it all. Or nearly all. He held on to the Trump Tower, but the planes, boats and other buildings (save the casinos) went. But he never filed for personal bankruptcy, which mattered greatly to him. One person said that if he’d been the Donald during this period he’d have thrown himself off a building. But Trump was chipper. “Survive through ’95” was his mantra.

After ’95, his style was a bit different. He continued to build but was careful not to over-leverage himself again. And by the time Mark Burnett, producer of The Apprentice, decided to sign Trump as the host in 2003, his brand was recovering. Donald was ready for prime time.

Which brings us to the Trump of the last decade. There really are two Donalds, agrees Pam Liebman, president and chief executive of the Corcoran Group and an old friend of Trump’s. There’s the public Donald with all the bravado—and then there’s the relaxed Donald whom you’ll see throwing a ball with a kid around the pool at Mar-a-Lago. “It might surprise people to know that he likes children. He’s produced three hard-working, unspoiled children, which, given their circumstances, is no mean achievement. That says a huge amount about him.”

“He was and is a very hands-on father,” says daughter Ivanka, who oversees acquisitions in the family business. “Perhaps more educational than most. But our relationship with him is real.”

Liebman says she often sees Donald driving Barron, his seven-year-old son, around on the golf course. “It’s very sweet to watch. Of course he tells us, ‘Barron is the tallest, the best…look, he has the best golf swing,’ ” she laughs. “He can’t help it.”

Trump and third wife Melania Knauss attend the launch of daughter Ivanka’s book with their son, Barron, in 2009

Trump and third wife Melania Knauss attend the launch of daughter Ivanka’s book with their son, Barron, in 2009

Barron is the progeny of Trump’s third marriage, to Melania Knauss, 43, a Slovenian model he married in 2005 after a seven-year courtship. (He also has a daughter Tiffany with his second wife, Marla Maples.) In his office, Donald hands me an article about Melania’s new jewelry line. “She looks beautiful,” I say. He jumps in: “She’s a beautiful person with a great, big heart who’s also a tremendous mother—she loves Barron so much. She is beautiful, but ultimately that is much less important than other ingredients. You know the beauty is good for the first ten minutes, right?”

It was Melania who put an end to his presidential ambitions in 2011 by telling him that of course he would win if he ran. The bigger question was, did he need to? “I thought Romney would win,” says Trump. “I really did. But he didn’t resonate. Even a lot of very strong Republicans did not get up and vote… I think the party is now very confused. They don’t know who they are anymore. And they’re falling into every single trap that you can fall into.”

The possibility of a Trump bid dominated headlines for weeks, as did his critiques of Obama. His repeated calls for the president to release his birth certificate, even saying he’d give $5 million to charity if Obama also released his passport application and college records, struck many people as extreme.

Does he think it was a mistake to have focused so hard on the birther issue? Donald One is adamant: “Not at all. It was a real question. It still is a real question. Most of the country really cares about this, and I don’t think we’ve got the truth. In fact, Vicky, you should look into it…you would win a Pulitzer…” It’s this doggedness that draws people close and also creates enemies. During our conversation, he harps again on his nemesis at Vanity Fair. “I don’t even look at that magazine. He sends it to me every month,” he says, conjuring up an imaginary note. “ ’From the desk of Graydon Carter.’ I don’t even read it. I just throw it away.”

Does he really care about negative press? “I wouldn’t call him sensitive,” says Ivanka. “But he doesn’t like being used and he doesn’t like being hit. So if somebody goes after him especially for no reason, he will hit them back harder. It’s who he is.”

Donald often asks those around him about social media. He finds Twitter a fascinating anthropological study. “The world is divided into two people: those who want the American dream and those who’ve failed.” The failures are the ones who don’t like him or understand him, he believes. Before making his reality debut, he says Regis Philbin told him, “Trumpster, just be yourself on TV”—and that worked.

It remains to be seen whether the public or media will ever accept both sides of Trump. But as our meeting ends, the Donald deep inside, Donald Two, wants to appear on the surface. “Just write a fair piece,” he says as he hugs me goodbye.

Momentarily he looks wistful. But then the room fills, and Trump is off looking at floor plans and buildings. Bankers are calling, and Donald is telling them all he can help…no need to repay the favor…