Silicon Valley startups tend to hog all the credit for kick-starting the open-office phenomenon. But these young technocrats have nothing on illustrious architect Robert A.M. Stern, who has embraced porous, partition-free floor plans since founding his practice in the late 1960s.

“All this talk of open environments—the Googles, the Apples—really started in architecture,” Stern explains. And he practices what he preaches: Private offices are practically verboten in the architect’s New York City headquarters, which is spread over five levels of a former printing press on West 34th Street. Stern’s own workspace on the building’s 18th floor seems more like a busy hallway than an inner sanctum. “People walk through it on their way to this place or that,” he says.

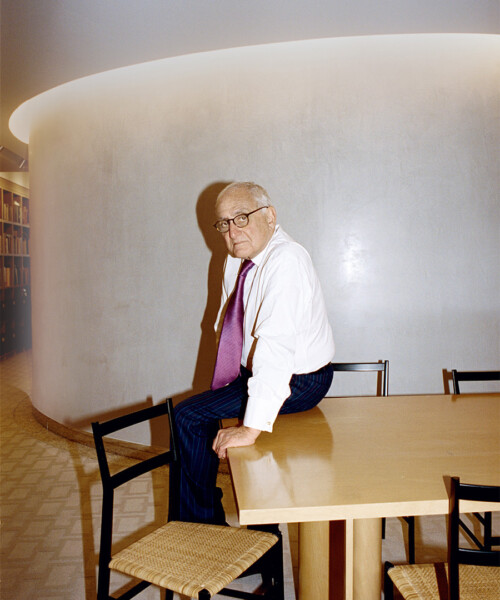

It’s a setup that perfectly suits his preferred way of working: in groups. For private meetings, Stern holds court in the penthouse three flights up, a book-filled haven boasting Hudson River views and a curated array of design classics: a Marcel Wanders floor lamp, Alvar Aalto lounges, Gio Ponti Superleggera chairs. But even this tucked-away space is communal, shared with the firm’s writing staff, who type away behind a curved partition wall. “The office is modeled on what I learned from my principal design teacher, Paul Rudolph,” he explains. Stern studied under Rudolph, the godfather of brutalism, at the Yale School of Architecture, where he received his master’s degree and now presides as dean. Since 1998, Stern has split his workweek between Manhattan and New Haven, where his office is similarly accessible: “There’s no door,” he notes.

Renowned for his historically minded designs, Stern is also lauded for contemporizing and making relevant the architectural vocabulary of pediments and pilasters. He is widely considered the guardian of classical architecture—and has a portfolio to back that up. His firm has designed 15 Central Park West, stately edifices for Ivy League campuses, the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas and the town of Celebration, Florida. This fall, Stern will unveil a hotly anticipated new residential project: 20 East End Avenue, a 17-story brick-and-limestone condo building featuring duplex townhouses and apartments graced with elegant millwork, oversized bay windows, Juliet balconies and a distinctly prewar-inspired élan.

But don’t confuse style with mindset or traditionalism with conservatism; Stern is a forward thinker—except when it comes to leasing office space. When he moved into his building 20 years ago, he signed on for just one floor: “I am always sure we are going to go out of business”—an unfounded fear for someone so successful—“so we didn’t take as much space as we should have.” As his practice has grown into the 325-person multidisciplinary machine it is today, with a scope that includes landscape design, interiors and product design, the office has expanded both upstairs and down. “One of the half-floors is not contiguous,” he says, “which is a mite inconvenient.” Not that he does much wandering these days. Stern confesses he was more of a roamer before computers became ubiquitous. “You can no longer just drop by and look on peoples’ desks to see what they are working on, which is unfortunate for the culture of any office.”

Stern is unapologetically old school when it comes to the artistic process and is a devoted practitioner of hand drawing. Every design—from a vacation home in Martha’s Vineyard to an urban master plan in China—is conceived via sketch and then built in Sculpey clay before a computer-aided design file is created. “Drawing has been virtually abandoned as a discipline, I think much to the detriment of the future of architecture,” he laments. “The eye, the hand, the brain—the cognitive sciences tell us they are intimately connected in the creative process.” He also finds that scale is hard to understand on-screen, one of the reasons he favors oversized architectural models. “I like to be able to put my head inside them, to look around and really see the structure of the space,” he says.

Stern is not anti-technology so much as pro-humanist. “I believe architecture comes out of other architecture, out of traditional forms, out of meeting the needs of human beings: how they walk and talk and see and sniff the air,” Stern notes. “Architects are so enthralled with technology these days that they don’t think about what it’s like to walk in the door.”

Though Stern likes to set theoretical limits to his workday, arriving at the office around 9 a.m. and clocking out at 6 p.m., his brain doesn’t seem to have an off switch. “Design is something you refine and refine and refine,” he says. “You don’t want to build your first sketch: You want to figure out what the idea was and evolve it and nurse it and baby it.” He is quick to dispel what he calls the Fountainhead myth of architecture—that the genius makes a sketch and calls it a day. Not exactly: “The genius works his ass off.” Just not behind closed doors.