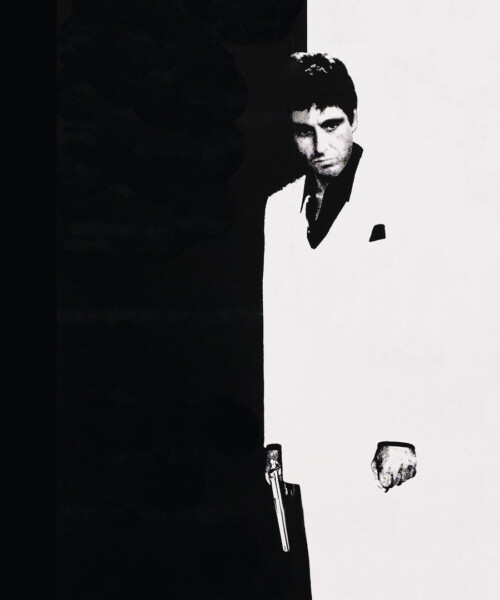

“Tony and his colleagues lived on the edge all the time. Violence could explode at any moment,” says screenwriter Oliver Stone

In Miami and Palm Beach in the 1980s, “it was like the Wild West,” Bregman says. But the filmmakers found the cops very cooperative—and competitive, too. Who could come up with the best anecdotes? They loved the idea of helping out a big movie that starred Al Pacino.

The police gave Stone endless case histories to read of murders committed over drugs. “Really horrific stuff,” Stone says. He incorporated many real-life details into his screenplay, including the infamous sequence when Tony is double-crossed with a chain saw in a Miami hotel room.

“Colombians did use chainsaws,” Stone said in a telephone interview from L.A. “They were the most blood-thirsty. They would kill entire families of drug pushers if they informed. Colombians were the most secretive.”

As part of his research, Stone traveled to Peru and Ecuador. “It was scary; my life was on the line.” In Bimini, in the Bahamas, he almost got killed. Most of his research took place after midnight and lasted until dawn: “That’s not a very safe time to be out alone when you’re dealing with guys who might have second thoughts about you after they decide they might have told you too much.”

The experience in Bimini put Stone in touch with fear. “Fear is the essence of Scarface. Tony and his colleagues lived on the edge all the time. Violence could explode at any moment. Fear, combating it and confronting it, like I had in Vietnam.”

Stone says he stopped doing drugs the day he finished his research and flew to Paris with his wife. They took an apartment and stayed there for six months.

“The heating was poor, but the food was good, and I had a whole new set of friends who were drug-free. I wrote all of Scarface there as a farewell to drugs, really.” He’d never worked so hard, he says: “Six or seven drafts.”

What emerged was a fairly schematic updating of the Howard Hawks original, the rise and fall of a punk with a 1980s twist. It started off with the sadistic murder Tony and his pal commit in the refugee camp in order to buy their freedom and get green cards.

“It was all terrific,” Pacino says of the script Stone turned in. “Explosive. Powerful. I felt that this Scarface was a piece of so many different kind of gangsters, a collective. In Oliver’s script, Tony was a renegade—angry, vindictive, weirdly funny. Out of control. And those lines of dialogue, like, ‘Who do I trust? ME!’ ”

Lumet, though, thought Stone’s screenplay was “corny.” He disliked the suggestion of incest (which was also part of the 1932 film). He wanted to introduce politics into the screenplay and thought that it needed to explore the CIA’s connection to drugs. Lumet said Stone’s version read too much like a comic strip, Bregman says.

Stone was devastated.

Bregman says, “Sidney wanted to make a different film from the film we wanted to make. He wanted to make a political film. We wanted the make it larger than life, more extreme. Exaggerated. Oliver Stone had achieved that in his script.”

Undaunted, Bregman called in director Brian De Palma, whose earlier films Carrie and Dressed to Kill had been great, nasty entertainments. “Brian really knows how to exploit the audience,” Bregman says. “He uses their fears and their desires to unify his films.” As soon as De Palma read the script, he was sold on Stone’s approach to the material. He says, “The theme reminded me of John Houston’s Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Man driven by greed into a homicidal paranoia.” In Sierra Madre, three drifters sell their souls on a quest for gold. “Gold was now cocaine, De Palma says.