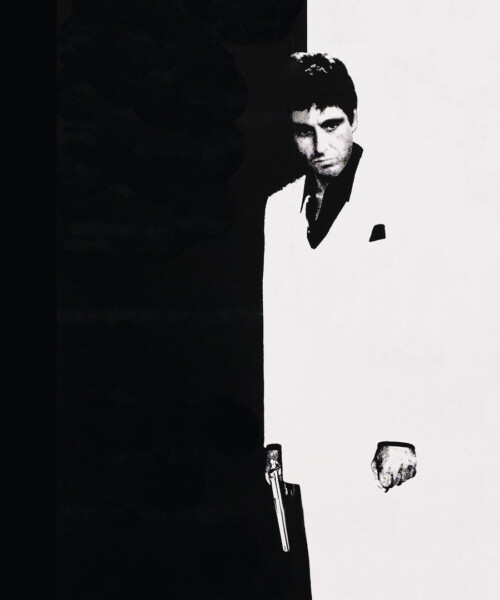

Michelle Pfeiffer as Elvira Hancock

Casting started in 1982 and went on for weeks, “because we wanted Al to be surrounded by the very best actors,” Bregman says. Robert Loggia, F. Murray Abraham and Harris Yulin won important parts. Ultimately the youthful Steven Bauer (then married to Melanie Griffith) was cast as Pacino’s loyal friend Manny. He was a bilingual Cuban-American and brought to the part “a nifty mixture of businesslike murder and lover-boy sweetness,” as film critic Pauline Kael would later write.

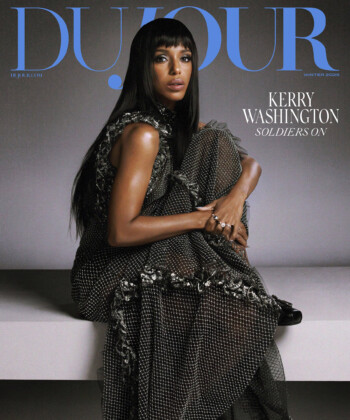

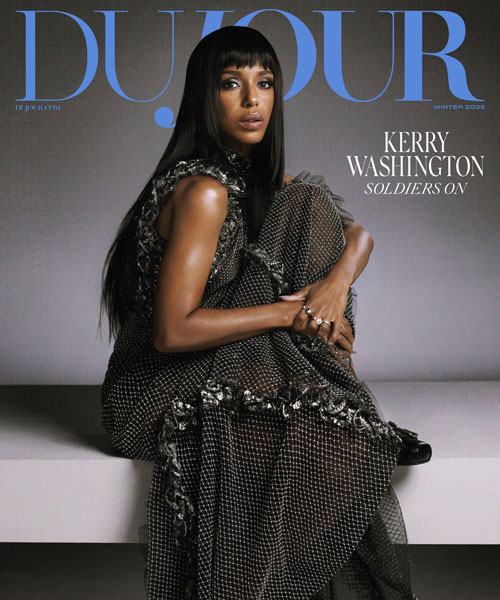

Michelle Pfeiffer, then 23, recalls auditioning over and over again for the part of Elvira, Tony’s fragile, coked-up wife. Pfeiffer, who had not that long ago been bagging groceries at a supermarket, says she auditioned for Scarface so many times she was sick of it, and “then they stopped calling me, and I wanted to forget about it.”

But she was called back to screen-test with Pacino: “I was petrified. I vomited before I went out on the set—I mean, he was one of the biggest stars in the world. I was just beginning.” They did a marvelous, intense scene together from the screenplay, she says—the one in the expensive restaurant where Elvira ends up walking out on Tony. “I was so keyed up my arms went flying and I broke a glass and cut Al. There was blood all over the place. I was sure I’d lost my chance.” But a couple of days later, her agent phoned to tell her the part was hers.

Pacino had been initially dead set against Pfeiffer as had Universal; they thought she was too inexperienced. But Bregman fought for her. He thought she was the best choice. He phoned Pacino and asked him if he wanted to see her screen test but Pacino said, “No, I trust you,” and he hung up.

The cast rehearsed for an entire month in California and New York. By fall 1982 the production was poised to start filming in Florida, but suddenly there were problems with the Cuban community in Miami. Opposition to the project was growing. According to Bregman, no matter how much he argued and pleaded that a great many Cubans would be employed in the production and that the movie wasn’t all negative, the locals wouldn’t be swayed. Bregman was physically threatened and hired a bodyguard armed with a machine gun. The last straw came when a Miami city commissioner demanded that the script be changed to make Pacino’s drug lord a spy sent by Castro to corrupt America.

The production shifted to Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, and the crew made the most of the second-choice locations. The refugee internment camp underneath the Miami freeway was re-created between the intersection of the Santa Monica and the Harbor freeways. Scenes set in Miami’s bustling Little Havana were shot instead in L.A.’s Little Tokyo, where the crew erected storefronts and Spanish-language billboards and used an evocative mural of the Miami skyline.

Pacino worked day and night with a dialogue coach to perfect a Cuban accent. He also spent hours with the makeup man, developing the scar. “I didn’t want it to be too big. I figured the guy was good with a knife. I imagine he might have been nicked during a fights, so I had two scars, one across the cheek and the other above the eyebrow. I liked that, because it suggested a chaotic wildness in the guy.”

In Santa Barbara the production rented a huge estate, a fortress-like Xanadu complete with a sunken bath and a private zoo where Tony Montana kept his pet tiger. Scenic designer Fernando Scarfiotti’s biggest triumph was creating the “Babylon Club,” a lavish fun spot for drug dealers and their friends. The place, built on one of Hollywood’s largest sound stages, was filled with tropical plants, gushing fountains and erotic Greek and Roman nude statues. The pink and blue neon lighting was so bright it hurt your eyes. “I wanted to do it all in Technicolor,” De Palma jokes.

According to Michelle Pfeiffer, “Brian could be stylistically obsessive.” Most of the time she had to slink around in glistening satins and sparkling jewels. “I was objectified. Not a hair could be out of place.” Once, she had a bruise on her leg and De Palma made her take off her panty hose and put makeup on the bruise to cover it. “He wanted no imperfections.”

Pfeiffer adds, “I was terrified all the time. I couldn’t speak to Al [off the set]; we were both too shy. It was like pulling teeth to say one word to each other. And then the subject matter in the script was so dark. There had to be a coldness in the relationship between Elvira and Tony.”

She goes on to say that she and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio were ignored by the mostly male cast: “All the guys were very macho, laughing and joking among themselves; we were never included.” She says she noticed a big difference between Pacino’s temperament when they worked together on Scarface and then, eight years later, on Frankie and Johnnie. In the later movie, Pfeiffer says, “He was a happier person.”

Occasionally during filming, shouting matches ensued, with Pacino and De Palma and Stone and Bregman all jumping in. “Al had all sorts of ideas about how things should be done, and so did I,” De Palma says. “But we worked it out. Sometimes he was right; sometimes I was right. But a lot of screaming and fighting did go on.”

A member of the cast who wants to remain nameless says, “The show was commandeered by Al. He was the real power. Brian had to listen to him in terms of acting values. We didn’t do De Palma’s version of Scarface, we did Al Pacino’s version—and don’t let anyone tell you differently.”

And then there was Stone, who would barrel onto the Universal soundstage every day. He was possessive about his screenplay—he was worried about cuts and changes and what he felt were differences of interpretation.

One evening after work, De Palma, Bregman and Pacino sat in a darkened screening room with Stone, who suddenly started talking back to the screen, “yelling stuff like, ‘What kind of dress does Michelle have on?’ and ‘Where the fuck did that line come from?’ ” Bregman says. Stone was not allowed back to see rushes again.

“Sometimes making a film is like going to war,” Bregman says.

In the last weeks, in spite of continued death threats, the cast and crew finally did go to back to Florida. There they shot the last scenes, in which Tony, high on coke, has a spectacular shoot-out with a Bolivian hit squad—and is finally killed, in a great burst of blood and smoke and noise, and plunges to his death in an ornate fountain.

“Al was on a rampage,” one of the actors remembers. “He’s yelling and screaming, ‘Say hello to my leetle friend,’ as he brandishes that bazooka-like machine gun—he seemed to go absolutely crazy all alone in that vast mansion with the mounds of cocaine on his desk.” At one point, Pacino gripped the barrel of his machine gun and it was so hot it gave him second-degree burns. He landed in the hospital, shutting down production for 14 days.

Throughout the whole dramatic shoot, Pacino stayed away from the rest of the cast. “Al didn’t talk to anybody except me,” Bauer says. “And then when he had to kill me in the movie, he stopped talking to me.”

Pacino says now, “As you do this more and more—acting, that is—you don’t mix up your parts and yourself so much.”

* * * *

NEXT: “Tony Montana is the antihero contemporary kids identify with.”