By 10:30 p.m. on a November Wednesday, the Whitney Gala was breaking up, leaving behind empty tables littered with wine glasses and graphically compelling desserts. Elvis Costello had played and Julian Schnabel, Jeff Koons, Hilary Rhoda, Padma Lakshmi, Riley Keough and other bold-faced names began to drift towards the doors. Some of the guests, perhaps buoyed by the fact that the event had raised over $4 million (seats started at $7,500 each) or that it was the last gala in the old Breuer building, wanted to revel more before calling it a night.

“Time to check on the children,” joked Kyle DeWoody, the 30-year-old daughter of Beth Rudin DeWoody, a collector and Whitney museum trustee. The “kids” in question were the 630 guests at the Studio Party, one of the gala circuit’s better junior after-parties, a more moderately priced, $250-per-ticket event attended by far dimmer names that was just getting started upstairs. Among them was a handsome and lithe man with a good head of pale hair who’d just finished posing for some photographers on the red carpet and who, at 43, was pushing the limits of “junior” membership. He was most definitely not a child.

“You look so nice,” a friend told him.

“I put on a tie tonight because it’s the last party in the building,” he said.

He was Kipton Cronkite (pictured in main at the Whitney Gala), one of the Whitney’s “Contemporaries,” the name the museum gives to its group of young patrons who pay $500 to $1,000 a year for access to benefits that include invitations to fundraisers and museum events and the potential of one day being asked to be part of a party planning committee. Committee participation has plenty of perks. Beyond the social and career networking opportunities at meetings in private homes or glamorous offices, members have access to conversations with curators and are invited for visits to artists’ studios and private collections. To be asked aboard the executive committee, it takes the recommendation and approval of a trustee, curator or fellow committee member, not unlike at a social club, although for less money and with different factors for qualification.

In recent years, these junior groups and the parties they host have become one of the nonprofit world’s most, well, profitable endeavors, largely by connecting with, and counting on, younger patrons eager to belong. Cronkite is a typical junior group member and committee aspirant: not quite arrived, but trying his damnedest to get there. Born James Kipton Cronkhite, he moved to New York in 2001 from his native Oklahoma after graduating from Oklahoma State University. When he hit New York, he changed the spelling of his last name, which helped open more doors. As he segued from working with high net-worth clients in finance to the art world, he found himself a sought-after guest with expertise. Artists liked that he was associated with business. Social people thought he was related to the aristocratic newscaster. That misunderstanding, which he didn’t bother to correct, landed him in tabloid trouble in 2009.

“I admit I have made some mistakes along the way,” he says.

But that didn’t slow him down. In the past 10 years, Cronkite has been on committees for a number of junior organizations, including the Young Fellows at the Frick, Young Patrons of the American Friends of the Louvre, the Young Collectors of the Winter Antiques Show and the New York Botanical Garden.

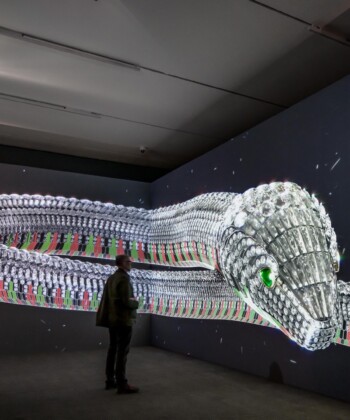

The night of the Studio Party, he stepped into the nightclub-like scene on the fourth floor, where the Studio Party had taken over with a DJ booth, bar and massive slide projections of the view from the new Whitney in the Meatpacking District. His fellow Contemporaries were all over the place and he went around visiting them like a pollinating bumblebee. He greeted Ariana Rockefeller, a fashion designer; Adam Abdalla, an arts publicist and co-chair of the Whitney Contemporary group; and Sarah Arison, a film producer who helped found Mr. Cronkite’s online art advisory. Like Cronkite, Arison serves on various committees around town and beyond. “It all dovetails,” she said.

Whitney trustee Joanne Cassullo, who joined the board at an unusually young age many years ago, watched the scene of drinking, networking, flirting and hair tossing with pleasure. “Are all the people at this party on the make?” a guest asked her.

“Ninety percent of them,” she said. In one way or another, at least.

Everyone knows that if it weren’t for its fundraising, New York would be a wasteland for arts and social services. The city has, for at least a century now, made charitable giving, and the parties it seems to require, part of the cultural fabric. In the decades until this one, grand dames such as Brooke Astor, Jacqueline Kennedy, Judy Peabody and Pat Buckley would lead the charge by chairing gala committees and charming friends into buying tickets and tables. They had family names with clout and were able to take charge because they were willing to do the work and, let’s face it, because they didn’t have jobs to distract them. They could chair committee meetings, court sponsors and rally friends on the phone. Many even wrote notes by hand to encourage contributions and followed up with thank-you notes as well.

But lately, the profile of committee members has been moving away from old society names to include people with marketing and social media savvy, connected friends and enough money (or desire to belong) to buy tickets and tables. While some organizations such as the New York Public Library, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Central Park Conservancy and Boys and Girls Club maintain some exclusivity, others can’t afford to do so. And so they establish junior groups and after-party committees that serve as permeable entry points for charmers like Cronkite and others eager to see their names appear on invitation committee lists. These are people who in a previous social era might have been shunned entirely—due to fake name or fake pedigree or both. Today, though, they do too much for institutions to be left out. They pay membership fees, buy benefit tickets and have a hand in planning parties as well as guiding the museum staff in its outreach and fundraising. The crowd is notably younger, and more single, and socially ambitious. They may not be among the few paying $7,500 for a seat at a table, but they are among the many willing to pay $250 for standing room only. The success of junior involvement has become so obvious that organizations now dedicate staff positions to managing young committees, which can bring in high-six-figure amounts in fundraising.

“New York is a city for people who want to get ahead,” says journalist David Patrick Columbia, who chronicles countless philanthropic events on his website, New York Social Diary. “And getting on a committee in New York is a way to get in with certain groups of people.” On the whole, Columbia, who can be a stern judge, sees committee culture as one of hardworking volunteers who believe in the mission of their organizations. He singles out Sloan Kettering committee members as particularly serious, as did a recent article in Town & Country about Eleanor Ylvisaker, founder of luxury fashion site FEYT who encourages her associates to pursue on-site volunteer work. But, adds Columbia, with something like dismay, “Some people are hustlers and publicity hounds.”

A New York Times story not that long ago singled out the particularly pervasive Jean Shafiroff. She has been chairing events with surprising frequency in Southampton, and was described as “twirling like a music box ballerina” for photographers as she entered the New York Botanical Society’s Conservatory Ball in June of 2013 and “hijacking” the “otherwise decorous affair.” Another figure, Lisa Marie Falcone, ruffled feathers when she walked up to the microphone uninvited at a benefit for the High Line and pledged $10 million.

“Look, Nan Kempner was a social climber,” says Debbie Bancroft, a columnist for Avenue who has chaired the gala benefit committee for the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. “But at least she knew how to do it. Some of these other people are just an embarrassment.”

It costs junior committee members like Kipton Cronkite thousands in membership fees and gala tickets. Cronkite freely admits the costs are offset by the benefits, as it were. “We have access—to collectors, curators and other insiders,” he says. And while he seems to be a worthy presence at the Whitney (“He’s great at connecting all kinds of people,” says Holly Strong, the Director of Institutional Advancement), not all committee members are equally appreciated. “Committees can be great or a pain,” says Anne Livet of Livet-Reichard, who has planned events for B.A.M., Bomb magazine and the Bronx Museum of the Arts. “You have to be careful they don’t go in the wrong direction.”

Indeed, when so many people have their own agendas—least of which, let’s be honest, likely includes planning a party—there is competition for billing and power. “The fighting is about who gets to be the chair or spokesperson,” says Couri Hay, who counseled Tinsley Mortimer about committee work when she first came to New York. “For all the people who want to do good for an organization, the politics can be brutal.” But then charity, as Oscar Wilde once suggested, creates a multitude of sins.

“A third of the people on committees these days are going for the exposure and don’t even know what the charity does,” says Bancroft, who once told an attention-grabbing charity chair that that her favorite philanthropists are anonymous. “If you chair more than three parties a year, you stop being credible.” Indeed, one writer who received a prestigious New York Public Library fellowship attended a cocktail party honoring her and her colleagues and could not help but notice that the committee members in attendance seemed more interested in speaking to one another than to any of the authors in the room.

All this is why some non-profit advisors caution organizations to know what they’re getting into before starting committees. “They can be exciting for members, but they can also be detrimental if you’re a smaller organization,” says Anne Pasternak of nonprofit public arts group Creative Time, which limits them. Larger institutions don’t have that option. And many don’t want it.

“As long as people bring something to the table, I’m OK with them fulfilling their own agendas,” says Livet, who will help organize the New Museum’s benefit in April. “I have more respect for people pitching in for any reason than being gadflies or flies on the wall.”

Nobody would accuse Cronkite of that. At the Whitney Studio Party, he worked the floor with a youthful vigor that belied his age. Soon it will be appropriate for him to think about moving from the juniors to the grownups, a much more expensive commitment that many aging junior committee members try to avoid for as long as possible. Patrick McGregor, a fashion public relations consultant and co-chair of the Whitney Contemporaries, watched Cronkite circle the room with something like amusement. “Over the years there’s been a big change in the face of committees in New York,” said McGregor. “And Kipton has been on just about every one of them. It’s no longer about a family name.”

Even when it’s Cronkite.