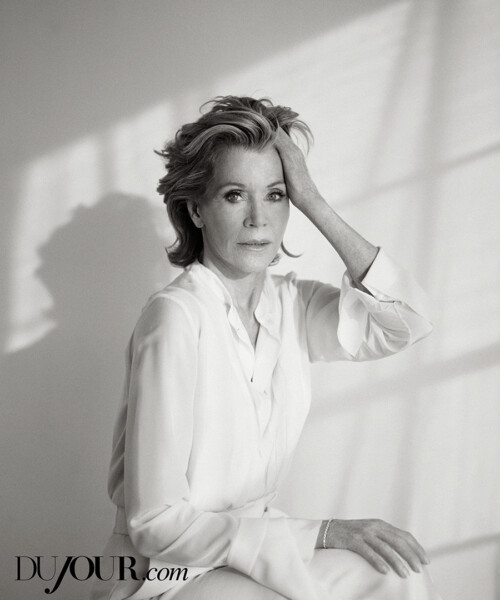

There are no seasons in Southern California, unless you count awards season. It’s a Thursday morning in early January 2015, the height of the trophy derby, and Jane Fonda is telling me about the night she won her first Oscar, in 1972, for her role as a reluctant prostitute in Klute. “I wore a Saint Laurent wool suit—black,” Fonda says, in disbelief. “A Mao wool suit that I’d had for five years. I never had a stylist. I didn’t know you could get someone to come and do your makeup. I thought you had to buy a dress.”

We’re seated at a corner table at Soho House, high above West Hollywood, settling into a deep tweed couch for a conversation about her new Netflix series, Grace and Frankie, which premieres in May. Fonda’s body is toned as ever, and she’s dressed all in black. Black turtleneck, black fedora and tall black boots over black leggings, with a dozen thin gold strands dangling around her neck. She’s chic as hell, pausing for a moment to take in the sunlit rooftop.

“My boyfriend said the heat wave is over, so I thought, OK, it’s gonna be cold. Then I’m seeing everyone looking way more California than me. But anyway.” When the waiter appears, Fonda, 77, orders a hot mint tea with honey.

“Peppermint or the fresh mint?” he asks.

“Make it fresh!” Fonda says. “Fresh sounds good.”

Fresh indeed. Fonda couldn’t have predicted how fashion would come to dominate the red carpet, but in every other conceivable way this woman has been way ahead of her time. While Bridesmaids was heralded as groundbreaking, Fonda’s Nine to Five did it back in 1980, earning $103 million. It was the second-highest-grossing film that year. Then there was the wildly successful Jane Fonda Workout, a revolution that not only changed the way women exercised but also is credited with creating the home-video market; there was no reason to buy a VCR in 1982 unless you were “doing Jane.” She’s also been on the forefront of social consciousness. In 2004, Fonda spearheaded the first-ever transgender production of The Vagina Monologues. Heck, she’s arguably the first celebrity to have had a reality show. In 1962, while rehearsing to open The Fun Couple on Broadway, Fonda let cameras follow her from the rehearsal room into her dressing room for a documentary called Jane (available through SundanceNow Doc Club). The footage was so raw, so revealing of a young woman’s psyche, that Fonda found it traumatic to watch the film, decades after the fact.

Now, some 35 years after Nine to Five, Fonda will be back onscreen with Lily Tomlin in a series about two women whose husbands come out as gay and leave them for each other. “It’s a tragedy, when you’re 70 and your husband leaves you,” Fonda says. Grace and Frankie may be a sitcom, but it’s also the story of having to rediscover yourself late in life and asking that terrible but essential question: Who am I? Fonda’s been asking that question for years.

When Jane Fonda left her third husband, CNN founder Ted Turner, in 2001, he wasn’t just hurt, he was flat-out confused. Fonda recalls Turner telling her, People aren’t supposed to change after 60. “I think about that all the time,” she tells me, sipping her tea. “He has hardly changed. And I feel like a different human being.”

We are never just one person over the course of our lives. This is true of most people but especially of Fonda, someone who would grow and stretch and mold herself searching for the skin that fit her best. While married to the French director Roger Vadim, she could be wild and carefree, as comfortable acting for him in a foreign language as she was with his predilection for bringing prostitutes into their bedroom. With the activist and politician Tom Hayden, Fonda would eschew glamour for the barricades. With Ted Turner—whom she still cares for deeply—she retired from acting completely to support him. Fonda acknowledges the dichotomy between her reputation as an outspoken feminist and the good wife she sometimes played at home, referring to this as a struggle with the “disease to please.” There is beauty—and knowledge—in that struggle.

“We all wonder what, if anything, we’re going to leave behind,” she says. “My ability to understand what my life means—to put it in a way that can be meaningful to other people—that’s the gift I would leave behind. It’s the strangeness of my life that is the most important thing about me, more than any particular part of my work.”

The first label slapped on Jane was “Henry Fonda’s daughter.” Rather than accept that, she dropped out of Vassar and fled to Paris to study painting. Returning to New York, she took classes at the Actors Studio, working twice as hard as everyone else to prove she belonged. She describes her 24-year-old self as “a human being underwater, barely making it one foot ahead of the other, and numb,” which is what makes the 1962 documentary Jane compelling: It’s a portrait of a woman at war with her instincts. Fonda watched it for the first time in decades while writing her 2005 memoir, My Life So Far.

“I pulled the shades down and locked the door and drank some vodka,” she tells me, “and sat on the floor and shook like this. It was so upsetting to me.” Of the decision to star in a play that didn’t have a finished script, let alone a point of view, she says, “The director wanted to do it. And he was my friend. So I said yes. I didn’t want him to be mad at me.” Why let cameras in? “Those were the days when I didn’t know how to say no.”

There are easy-to-spot patterns in her life. From the outside, she and Roger Vadim had a romantic fever dream. But Vadim accused her of being “bourgeois” and pushed for an open marriage. “One night he brought home a beautiful red-haired woman and took her into our bed with me,” Fonda writes in her memoir. “She was a high-class call girl employed by the well-known Madame Claude. It never occurred to me to object. I took my cues from him and threw myself into the threesome with the skill and enthusiasm of the actress that I am.” What’s more revealing is what happened next. “I’ll tell you what I did enjoy,” she writes, “the mornings after, when Vadim was gone and the woman and I would linger over our coffee and talk. For me it was a way to bring some humanity to the relationship, an antidote to the objectification.”

Vadim wanted Fonda to star in Barbarella; he liked the script but was mostly interested in it as a directorial vehicle for himself. A sci-fi sex romp isn’t a natural fit for an actress battling with bulimia. Perhaps the film at least made her feel sexy? Not until years later, she says, telling me a story. “The first week I was dating Ted there was this big rally in Hollywood and my job was to introduce Virgin Airlines…”—she pauses to think of his name—“Richard Branson. So, I introduced him. He came up. I started to leave the stage, and he grabbed me and he pulled me back. He said, ‘You really owe me.’ I looked at him. And he said, ‘I was 15 when I was circumcised. I still had the stitches in when I watched Barbarella. And you made me burst my stitches!” She laughs, adding: “Isn’t that a strange thing to say in front of 3,000 people?”

Fonda’s activism came to the forefront during her time with Tom Hayden. Still evolving, still moving, still doing the personal growth work most of us only talk about. She was hanging with the Black Panthers and leading anti-war rallies, insisting on doing issue-oriented films like The China Syndrome and Coming Home. (If you still think she’s somehow un-American, her apologies for that infamous Vietnam photo are numerous and—most importantly—wholly sincere. She said she regretted it the moment it happened, and her track record of philanthropy should count for something, too.)

On paper, it was an odd time for her to launch a fitness empire. But Fonda needed a revenue stream to bankroll her husband’s political career. His nonprofit, the Campaign for Economic Democracy—which supported progressive candidates—was the exclusive owner of the Jane Fonda Workout, which is kind of funny considering Hayden’s distaste for Hollywood. When Fonda won her second Oscar, in 1979, Hayden cheered from the audience with their son, Troy, on his lap, but he turned up his nose at Tinseltown’s glamour. Of the Oscars, Fonda says: “I wore a dress that a Tom supporter had made. I went home after. In a station wagon. Because Tom didn’t like going to those parties. I never went to a party. Ever.”

Fonda was somehow still teaching aerobics classes three mornings a week in Beverly Hills while filming Nine to Five. Forget Goop. It’d be like Gwyneth Paltrow baking gluten-free banana bread for your kid’s bake sale. But Fonda would shed that skin, too, marrying Ted Turner in 1991 and retiring from acting entirely after seven Oscar nominations. The mogul’s world was seductive, in more ways than one. On one of their first dates, they flew to Big Sur on his jet and Turner introduced Fonda to the mile high club. “Before I could inquire about the logistics,” she writes in her book, “a fully made-up double bed materialized where just minutes before there had been a row of seats.”

NEXT: “The challenge is to stay angry and at the same time not burn yourself out or get an ulcer.”