It would be a stretch to say Joan was an accidental real estate investor—no one buys buildings in New York City by accident. But it would be fair to say it wasn’t on her list when she was first thinking about careers. “I thought I would teach forever,” says Joan, a former professor of finance who declined to give her last name. “Then my mom got very sick.”

So she stepped into the family business her mother had run since the death of Joan’s father many decades earlier. Turns out Joan had a gift—and ambition. She transformed a single Manhattan residential building into a real estate empire. But learning to manage her newfound wealth proved a challenge equal to expanding the company. Despite her obvious business sophistication, Joan says, “I operated in ignorance” when it came to her own finances.

For a long time, money, even more than sex, was a taboo topic of discussion among women, largely because men were in control of most of it. But a new fleet of female power players is leading an army of women into the realm of major wealth. According to the Spectrem Group, women under 56 now account for nearly 40 percent of wealth among adults who have a net worth in excess of $25 million. In small gatherings all over the country, they’re re-casting the chatter and turning to each other to discuss how to handle all this cash.

“There was a time when money was not considered a proper subject for ladies,” says Muriel “Mickie” Siebert, the first woman to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, 45 years ago. It’s why people like Joan had nowhere to turn for advice on earning and spending and saving. That began to change when the activist Elinor Guggenheimer called Siebert to describe a road trip she took with her husband to visit his Yale Law School buddies. She had an insight: Men have a network, but women do not. Guggenheimer’s response was to launch the Women’s Forum, a group connecting that rare breed of female executive, especially the ones who were unprepared for their success. Even if they “made it” they often stumbled, sometimes badly, in managing their money.

“When I sold my first company I got this big check,” recalls Joyce D. Reitman, an angel investor and serial entrepreneur in San Francisco. At the time, she was surrounded by big-time dealmakers—lawyers at Wilson Sonsini, a Big Four CPA firm—but no one ever suggested she seek help managing her windfall. And so she didn’t. Like many female entrepreneurs in the late ’90s, she figured she could handle it herself. “I wish I had had someone like me standing there telling me ‘Okay, let’s map out the things you want to do in your life,'” she says. Instead, Reitman says she became a somewhat haphazard investor, putting money into things that came her way but not creating a strategic plan.

Joan says it took her years to figure out how to manage her wealth. After refinancing her first building, she says she gave some of the cash to a neighbor, a stockbroker, to invest, almost as an afterthought. Fortunately, she didn’t give him a lot. The broker put some into a high-technology fund at the peak of the dot-com bubble, and the fund went to zero.

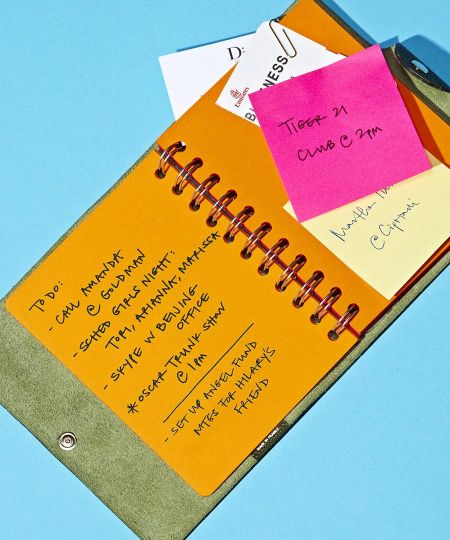

Such experiences have led women to try to fill the void with education. A few years ago, Joan found Tiger 21, a peer-to-peer investment group for the ultra-wealthy, where members bare their financial souls in workshops like “Portfolio Defense,” a form of asset-management group therapy. But Tiger 21, and other groups like it, is a male bastion, and many women prefer a place where they can create their own brand of money talk and focus on connections and the satisfactions that come with boosting each other. The Silver Bridge Institute in Boston aims to educate wealthy women through programs like “A Woman’s Perspective.” One recent lunch on financial fundamentals promised to help attendees learn the basics of money management so they can “work effectively” with their family, advisors and partners.

“Women like to learn and engage in really different ways from men,” says Dune Thorne, a partner at Brown Advisory who has been involved in teaching women about finance for the past decade. They organize themselves around “community, trust and collegiality.” Unlike men, women don’t want to talk products and returns as much as they want to talk about collaboration. While men view money as a means to power or independence, women with money tend to want to focus on interdependence and relationships, says Kate Levinson, author of Emotional Currency: A Woman’s Guide to Building a Healthy Relationship with Money.

Take, for example, designer and retail queen Tory Burch, newly enshrined in the church of billionaires, who’s putting a personal spin on charity by focusing on microfinance for women entrepreneurs. Spanx creator Sara Blakely, who is, at 42, the youngest self-made female billionaire on the Forbes global round up, says she wants to change the world “one woman at a time.” Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg, whose net worth is about $500 million, is known for throwing monthly dinners for women rising in the ranks.

Of course, these groups and gatherings give women a haven to discuss the emotional side of money, too. However they reap their wealth, women nearly always bear a mantle of guilt. When they earn it, there’s a part of them that feels they may have sacrificed their marriages or their children, says Helen Dietz, president of Stanford Investment Group.

When they get it through divorce or widowhood, there’s a different kind of guilt. Women may try to allay it through charity. Or, when they look for help with their finances, they may seek to replace the missing male in their life—and they don’t always make the right choices. One female broker recalls how prospective female clients would consistently select men who were charging them more money for the same services she offered. Barbara Stanny unwittingly married a compulsive gambler who spent the entire fortune she had inherited from her father, Richard Bloch, a cofounder of tax empire H&R Block. She didn’t even realize her money was disappearing until she got an “insufficient funds” message at the ATM.

Women’s very different set of goals and approach to money is what can make them vulnerable but it’s also what makes them effective, says Hannah Kain, CEO of ALOM, one of the largest women-owned private businesses in California and the wife of an entrepreneur. Women aren’t risk-averse, but they’re more risk aware which means they’ll not only give money to places where they also give their time but also seek out investment firms that value trust and connection.

“For women, it’s about relationships and the satisfaction we get helping others,” Kain says. Adds DeAnne Steele, a managing director and investment executive at U.S. Trust, “It’s not about a name on a building.” Not that something like that is out of the question. Not anymore.