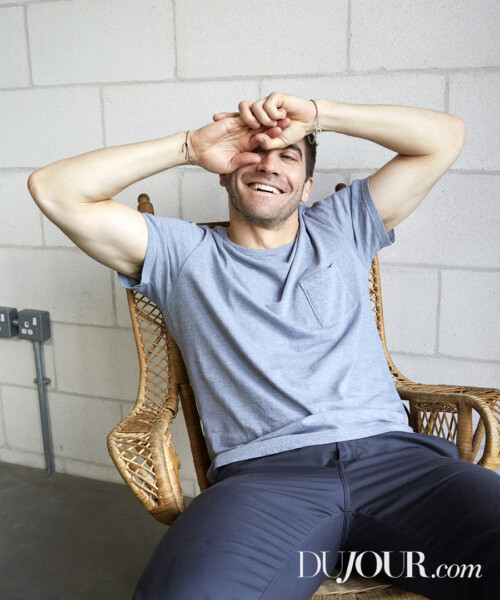

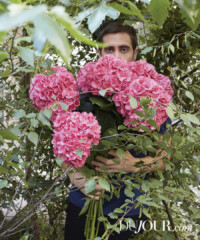

“Thank you so much for being so patient. I’m sorry this took so much time to schedule.” Before I can even introduce myself to Jake Gyllenhaal, he is apologizing to me. It’s a blustery Saturday afternoon in October and we are in a room deep in the bowels of the New York City Center theater in midtown Manhattan, where the actor is rehearsing for a benefit performance of James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim’s musical masterpiece Sunday in the Park with George (in which the New York Times will later declare he “shines”). Jake sings the lead, which is known as one of Sondheim’s most difficult parts for a man. I commend him for taking it on, and remark how, with such a short rehearsal process, he must not even have had time to doubt himself.

“Doubt is forever your friend in that moment,” he says. “But why do we pretend we are not overwhelmed, or we don’t like the feeling? The other day, I turned to Annaleigh Ashford, who plays Dot, and said, ‘This is why we do this.’”

Throughout our conversation, Gyllenhaal will talk this way: philosophically, artistically, passionately. He is head-to-toe Actor-as-Artist. During our chat he will quote Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 29,” praise the text of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This and extoll the under-sung musical theater actress Ellen Greene as “a national treasure.”

Between these inspired tangents, we discuss the work Iʼm there to talk to him about: his performance in Tom Ford’s highly anticipated noir thriller, Nocturnal Animals, out this month. Ford directed the film and wrote the screenplay, which is adapted from Austin Wright’s novel Tony and Susan. Gyllenhaal received the script last year as he was finishing the Broadway run of Constellations. “I read it and was immediately like, ‘Yes. I’m in.’”

The film is suspenseful to watch and gorgeous to look at (the director is Tom Ford). It follows Susan (Amy Adams), a chic L.A. gallerist who receives an unsolicited manuscript from her ex-husband, Edward (Gyllenhaal), whom she’d left years prior. Edward dedicates his novel to her and, as she reads it, we watch his character’s story unfold: Tony (also played by Gyllenhaal) is traveling with his wife and daughter along a dark Texas highway when they are forced off the road by a trio of joyriders. Something terrifying and tragic occurs, and Tony spends the rest of the film in mourning, haplessly seeking justice. Meanwhile, Susan has flashbacks about how she cruelly ended things with Edward. The story is violent, relentless. Neither of Gyllenhaal’s characters fares very well.

“That was actually a very difficult experience for me, emotionally, because there was no opportunity for retribution,” Gyllenhaal says, recalling the production. “I don’t think I ever really [did] get out of it in a way.” But before my mind can conjure an image of him as one of those actors who terrorizes everyone on set by screaming in an accent, he interjects, “It’s not like I’m walking around in character all the time, but I think the mood definitely [was] pervasive in everything that I did while I was making it. But,” he adds, “I think film, generally, in my opinion, is a lonely place.”

It shows. In scene after scene, we see Gyllenhaal portray a man coping with deep pain and loss. He’s right—there is no retribution in the film, and no redemption either. Everyone in the movie is a menace to Tony. Even Bobby Andes (the brilliant Michael Shannon), a laconic detective who works on the case, never appears fully trustworthy. Tony is alone in a highly stylized, very Tom Ford-ian universe.

“I found sadness in the fact that everything was about aesthetics in this world. I was living in a space where I was like, ‘Where is the truth here?’ I walked through it like that the whole time—and I think that’s where Tom wanted me to be.” Gyllenhaal’s special kind of vulnerability means he’s often called upon to provide this kind of sensitive dedication to a role—even when playing someone as emotionally stunted as Louis Bloom, his nihilistic newshound in Nightcrawler.

“Jake managed to find the humanity of the character,” says Nightcrawler’s writer and director, Dan Gilroy. “That was a worry I had with the script. I didn’t want this to be another study of a sociopath. Jake found a human quality not easy to find.”

“Honestly, for me, there was no other choice than Jake,” Ford says of his leading man. “The arc of his character(s) demands a huge range of emotion and performance. He starts off as a young, idealistic and pure 24-year-old, and ends up as a 44-year-old who has literally had everything he values stolen and destroyed. Jake is heartbreaking in the role.ʼʼ

It turns out Gyllenhaal wasn’t the only exposed one on set. The pressure was on for Ford, too. His acclaimed filmmaking debut—the dreamy, luxurious A Single Man—was seven years ago. Was his foray into cinema beginner’s luck? “He was together, commanding,” Gyllenhaal says of his director. “But he was very vulnerable, as much as Tom Ford can be.” The actor recalls a telling off-camera moment while filming a scene where his character was to be seated at an untidy desk. On set, the desk in question was perfectly neat, prompting Gyllenhaal to push the point with Ford. “It says [in the script] it’s really messy. Tom’s like, ‘Well, you mess it up, I don’t know how.’ His own struggle with aesthetics [was], could he, as Tom Ford, let go of being organized?”

Whatever the emotions that drove the men, they worked. The tensions between real and unreal, between order and chaos, crackle throughout the film. The smallest moments (a paper cut, spilled sugar) are as striking as a gunshot. Gyllenhaal’s performance is perfectly calibrated. He eeks out just enough emotion in certain scenes; in others, like one where he breaks down crying in the shower, he embodies anguish. His co-star Shannon agrees. “Jake is, uh, he’s an animal,” he says. “Very fiercely devoted to the craft—relentless. He’s really searching. He doesn’t let himself off the hook. He’s never satisfied. He’s really tenacious. He’s a beast.”

But these days, to survive as an actor in Hollywood, tenacity is just one helpful attribute. You also have to train like an Olympian and remain eternally poised, or risk the consequences of becoming a headline in thousands of gossip outlets. You can tell Gyllenhaal was picked for fame early and given very sound advice on how to be a Professional Lead Actor. Since achieving acclaim on the big screen as a doe-eyed teen with dark leanings in Donnie Darko, Gyllenhaal has more or less been recognized for his potential. But he bristles when people assume he “made it” because his parents were “in the business.”

For what it’s worth, the story of his family’s ascent in the entertainment industry is more inspiring than the reductive label of nepotism would imply. His father, the director Stephen Gyllenhaal, the oldest of six, came from a small town in Pennsylvania called Bryn Athyn. “He sort of left the town and went to college, but then fell in love with making movies,” says Gyllenhaal. Jake’s mother, Naomi Foner, a screenwriter, grew up in Brooklyn. Her mother was a pediatrician and her father was a surgeon, but she also broke free, to follow her passion as a writer. “As a child, you move to where you feel there is love. I think the place where I felt that love really existed, particularly between my parents and in my family, was through expression,” he explains.

Gyllenhaal, who moved from L.A. to New York City four years ago, says he did so to follow his great love: theater. “I did one show on the West End in London when I was 22 years old. And then was convinced by a lot of people at a certain age, when I was very impressionable, that it was more important to be doing movies. I’m thankful for that because, you know, it’s wonderful financially—but I think my heart has always been on the stage.”

Since taking root in the city, Gyllenhaal has won the theater community’s heart not only with his showings in Sunday and Constellations, but also with his now-legendary concert performance in Little Shop of Horrors, alongside the aforementioned Ellen Greene. Still, the actor won’t be breaking up with the cinema anytime soon: In addition to Nocturnal Animals, he has three films forthcoming. There’s Stronger, in which he plays Jeff Bauman, a survivor of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing (the actor doubles as a producer on the film, alongside his business partner Riva Marker). Also out next year are Okja (in which he stars opposite Tilda Swinton) and Life (co-starring Ryan Reynolds), which just wrapped. “And then,” he adds, “I’m doing a movie with Carey Mulligan that Paul Dano wrote and directed, called Wildlife, which [Riva and I] are also producing. And then I’m having some time off.”

Finding the courage to sing Sondheim is one thing, but to play Bauman—who lost his legs in the terrorist attack—is quite another. Especially while juggling four other projects. But at this point, Gyllenhaal seems confident with “his process,” which, ironically, includes not being too stiff or controlling about his process.

“There are many beakers that I’ve been mixing some pretty funky solutions in, to see what comes of them,” he says. “Not in a particularly unsafe, or safe, way, but always mindful… I think I came to the realization that acting is not just one thing. There is not just one way.” Moving in and out of a character needs to be done carefully, and Gyllenhaal is seasoned enough to know he needs balance. “There’s this growing notion—there always has been with actors, in particular—that the real great ones are the ones who mess themselves up somehow. I’ve always wanted to dispel that idea. I really don’t condone the idea of hurting oneself.”

As he says this, it’s impossible not to think of Heath Ledger, who starred alongside him in Brokeback Mountain and posthumously won an Oscar for playing the Joker in The Dark Knight, a role we now know may have consumed him. These thoughts yield a string of possible questions—‘How did you deal with Ledger’s death? Is it hard to find someone genuine when everyone wants you? Are you currently in love?’—but I know better than to ask them. When faced with inquiries like these, actors tend to answer in careful abstractions, as if their work were a relationship. But with Gyllenhaal, you get the sense this isn’t deflection: He isn’t lying when he says the theater is his greatest love.

“You can spend your life looking for this idea of what you think love looks like,” he says. “Or you can actually open yourself up to the things that are capable of loving you, and that you are capable of loving. And that means people who are of like minds. Finding the space that you love—I think that’s the biggest thing that I feel.” After spending so much time in the “lonely place” of film, it seems branching out into Broadway is giving Gyllenhaal some much-needed connection and community.

But, to play armchair psychologist, I get a sense of solitude from Gyllenhaal. After all, he is an artist, and one who knows he needs to cultivate a certain isolation and discipline in order to keep his channels open. Painters go to studios; actors go inside themselves.

“My imagination is becoming more and more important to me. When you go too far into the reality of something, you kind of destroy your imagination,” he says, explaining these sentiments are ones he’s adopted lately, especially after shooting Stronger. The serious, with a capital S, actor, who has been intensely working his tail off throughout his career, is ready to loosen his grip a bit. “I sort of went, ‘wait, there’s another way of doing it. Time to play a little more, have a little bit more fun in what you create.’”

I start to wonder if Gyllenhaal is like me, and like other New Yorkers in the arts who, after so many years of passionately pursuing creative projects, often at the expense of things like a relationship, finally realize it’s time to enjoy ourselves a bit more. I think about posing the thought to him, but before I can, he emits a yawn that politely signals our time is done. He needs to get going. Sunday has yet to open, remember, and he has much to rehearse. Grabbing his giant binder of a script, he puts on a coat and sunglasses and heads off to the next project in the fulfilling relationship that is also known as his life.