Bill Nighy is in California, and he has his eye on a banana. He arrived in L.A. the week prior (positively “a treat, coming from snowy, ice-bound London”), drove down to Santa Barbara for the film festival, and then up to San Francisco. He’s had his picture taken at the Bay Bridge and the City Lights Book Shop, and contemplated the burnt ashes of Jack London’s house at the author’s namesake museum. But today Bill has been very busy with official movie business, and it’s lunchtime, and he’s hungry.

“I’m looking at a banana and I’m thinking, ‘Will Frances mind if I eat the banana?” he says. “Because I am a bit faint. No disrespect to you, Frances, but I’m going to eat this banana while we speak. And I may have some coffee, which always makes me more interesting. A double espresso and I become fascinating.”

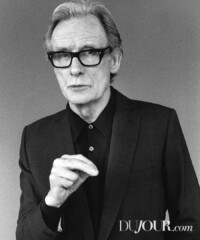

Nighy is a virtuoso at that time-tested technique of addressing the person he’s speaking to by name, but when he does it there’s no trace of smarmy-salesman faux familiarity. A lifetime theater actor, Nighy has said he spent much of his professional existence in a state of near crippling self-doubt. But then a very unexpected thing happened: the British thespian was cast as the indelible Billy Mack—washed-up “ex-heroin addict searching for a comeback at any price,” in 2003’s Love Actually. (Nighy will reprise the role in Red Nose Day Actually, the highly-anticipated short film sequel airing on NBC on May 25.) Ever since that late-in-the-game break, the 67-year old actor has had both feet planted firmly in the world of big-budget pictures.

Before he returns as Billy Mack, however, Nighy will grace the big screen in Lone Scherfig’s Their Finest, a World War II romantic dramedy that follows a young woman hired to make a propaganda film aimed at boosting the troops’ morale. Nighy plays a high-maintenance aging actor—a charming, self-deluded, benevolently pompous older gentleman, if that sounds familiar.

While Bill eats a banana, we chat about why he goes to the movies, why he loves suits, and why we—at this moment in history—find ourselves in a state of crisis.

What drew you to Their Finest?

I love the film. It’s one of the best I’ve ever been involved in, and it makes talking to people easy because I don’t have to dissemble in any way. My thing with the movies, since I was a kid, is that you go to the cinema feeling one way, and you come out feeling different—hopefully with a bit of optimism and inspiration. That’s what this film does: It makes you feel that things might just work out. And in current times, or any times, we really need things like that. In terms of feminism, it’s very important— particularly for a young audience—to see how women were treated not so very long ago, and how much progress there is still to be made.

When you started working on this movie, did you think that its message would be so prescient?

I always knew it had great things to say. I wasn’t aware they would be so much more necessary now. To show how in truly dangerous times people can remain compassionate and come together and have the courage to be kind and inclusive with one another—rather than divided and toxic—is always valuable. But there is an emergency situation now, which makes it even more necessary.

There’s a funny moment in the film when you think you’re being cast to play the romantic lead, but then realize you’re going to play the drunk uncle. Has anything like that happened in your own life?

I think everyone’s slightly delusional, including me. I remember one particular call from my agent saying “Darling, it’s Hamlet. It’s Moscow, it’s 18 months, it’s a tremendous gig.” And I said “I don’t want to play Hamlet,” and she said “No, no darling, not Hamlet—Claudius.” And then you realize you’ve become Hamlet’s uncle. I was 39 at the time, and I realized that the days I might be asked to play the Danish prince—even though I’d never wanted to—had in fact gone. There’s always that difficult period, in your late thirties, early forties, when you go up for parts and you hope it’s a good morning or a good hair day, because you’re treading a very, very thin line between a leading man and a character man. It’s a relief when you get to my time in life, because it really doesn’t matter what kind of day I’m having—I’m going to look like this anyway. So I’m fully over the line and into character world.

Do you think there are too few leading roles for older people?

I was in a film called The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, which, very surprisingly—I think for everybody, at least for me—took in enormous amounts of money. So they realized that older people will go to the cinema if you make movies that interest them and feature them. And now there’s been a whole spate of films about the romantic concerns of older people. It’s all about marketing—which famously invented teenagers, you know, so they could sell them stuff. And now they’ve scheduled all of our lives for marketing purposes. That’s kind of bled into the way that people think about themselves. When they pass a certain age they feel they’re disqualified from certain things. They think, “I’m too old to wear that, I’m too old to do that, I’m too old to have love in my life or travel the world or do extreme sports”—well, I really am too old to do extreme sports—but it’s almost funny, the fact that before marketing, none of that happened.

There’s a role you often play—a charming older man with a slightly bloated ego. When did you first tap into your ability to play that comedic part so naturally?

I don’t entirely remember, but I do remember that when I was young I found it very difficult to take myself seriously in a romantic role. I was deeply self-conscious because I made the mistake of thinking I had to “be it” rather than act it. The irony is that when I got old enough to realize that you just have to act out that stuff, I was too old to play those parts. But I had an agent who was clever enough to send me for parts that I wouldn’t normally be considered for. They used to call it counter-casting. It was a long time before I was given any comedy parts. I was in my thirties before anybody asked me to tell a joke. I never thought of myself in that way.

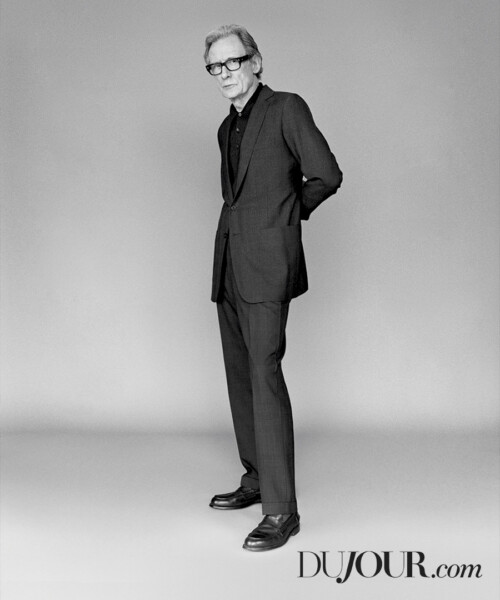

Let’s talk about suits: You love suits.

I’ve worn suits since I was a young man, usually because they were costumes and I got them half-price. I never had any money, and you could always do a deal with the costume person. I’ve never recovered from the phenomenon of the two-piece suit, or what we used to call—and it makes me laugh—the “lounge suit.” The casual thing, I try not to think about it. I have a theory that people who were destined for white-collar futures, when they come into show business, they dress down. They make appalling mistakes like tracksuit bottoms and rugby shirts with the collar turned up. Sneakers, trainers. Or they’ll wear shorts, which is unforgivable. But men who are destined for blue-collar futures, which I was, dress up. When Jarvis Cocker, the lead singer of Pulp, was asked why he always wore suits, he said, “You never know who you might bump into,” which I think is a very good answer. Basically it’s because I’m very insecure about my body—I don’t like anything about it and I figure the suit will always be in better shape than I am. I put a suit on and think, “It’s over, it’s done. I can relax now.”