In 1975, freshly minted Princeton grad Christopher Forbes organized an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was 24, and already selling ads for his father Malcolm, publisher of Forbes magazine. “I wrote a catalog instead of a regular paper for my senior thesis and the Metropolitan Museum asked if they could have it first,“ says Forbes. “I brought a lot of my clients to the opening. My father said, ‘Maybe he’s onto something.’”

Now, as the first American president of La Biennale, Paris’s premier arts and antiques fair, Forbes is up to his precocious 24-year-old ways. Come September, when the sprawling show takes over Paris’s glass-domed Grand Palais, Forbes will again use his golden Rolodex as an outlet for his obsession with art history. “I spend a lot of time with people of means who are also interested in art,” he says. “So I hope to bring a few of them with checkbooks in hand to the halls of the Grand Palais.”

This year is one of many firsts for La Biennale. Besides crowning Forbes president, the fair also changed its name (formerly “Biennale des Antiquaires”) and went from biennial to annual— an effort, says managing director François Belfort, to compete with more frequent international expos. “In the ’50s, every two years was enough,” says Belfort. “But now, with some fairs happening twice a year, if you’re not changing with the rhythm, then you’re forgotten.”

While some yearly fairs, like Art Basel Miami, have become as much about the after-parties as the art, don’t expect a Biennale bacchanal. “We are one of the oldest fairs, so we have an identity unto ourselves,” says Belfort. “Our identity is quite different from Art Basel.” Not that La Biennale has been without drama. Last year, a reduction in exhibition space caused an exodus of major jewelers like Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Boucheron.

With his academic demeanor and moneyed relations, Forbes could be just the quarterback to navigate the fair’s momentous changes. His family has been on the frontlines of the 1% ever since B.C. Forbes, Christopher’s grandfather, founded Forbes business magazine in 1917. In 1982, B.C.’s son Malcolm originated the “Forbes 400 Richest Americans” list, and in 2000, under the tutelage of eldest grandson Steve, Forbes introduced the Global CEO Conference, a watering hole for the über-rich and an early model for today’s various and sundry leadership summits.

And yet, Forbes’s idiosyncratic tastes make him somewhat of a black sheep, even within his own family. For decades he has nurtured an intense fascination with Napoleon III (his brother Steve, by comparison, collects alpha-dog Winston Churchill memorabilia). Just last year, at the behest of his wife and children, he auctioned off over 2,000 objects related to Bonaparte’s lesser-known nephew.

Naturally, as grand marshal of La Biennale, Forbes’s Francophilia will be at full tilt. That weekend, he plans to bring a group of guests to Balleroy, his French chateau in Normandy. “The house is the earliest surviving work of the architect François Mansart,” Forbes says. “The Mansart roof was a tax incentive in 17th-century France because it added an extra floor that was technically part of the ceiling (French homes were taxed by the number of floors below the roof line). Architectural genius, like everything else, was inspired by a tax cut.”

And while Steve may have inherited Malcolm’s seat at Forbes, as La Biennale president, Christopher will, to some degree, be the one retracing his father’s footsteps. “For years all he did was bring clients [to the chateau],” says Forbes. “When he took them on his boat, he would say, ‘CEOs think they can walk on water and they never want to prove it.’ Which is to say, they’re yours while they’re on board. And it was the same in Normandy; when they’re your guests, you get to work on them the whole weekend long.”

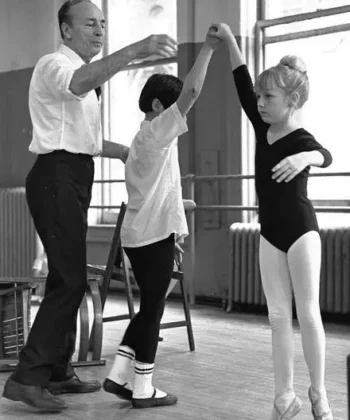

Christopher’s unusual taste in hobbies also seems to be passed down from Malcolm, who once held the largest collection of Fabergé eggs outside the Kremlin. “The Kremlin had 10 and my father had nine and a half,” Forbes says. Malcolm also loved hot air balloons, which coincidentally, was the theme of La Biennale when Karl Lagerfeld served as interior designer in 2012. “[Christopher] is fascinated by hot air balloons because his father used to organize them at Balleroy,” says Belford. “So that’s an object that’s a link between [the fair] and the Forbes family.”

But as La Biennale president, Christopher achieved something his father never did: combining his artistic and professional pursuits. “He wouldn’t have done [something like this],” says Forbes. “He was so busy doing so many other things for the business.” As Malcolm might say, if he were alive today: Maybe he’s onto something.