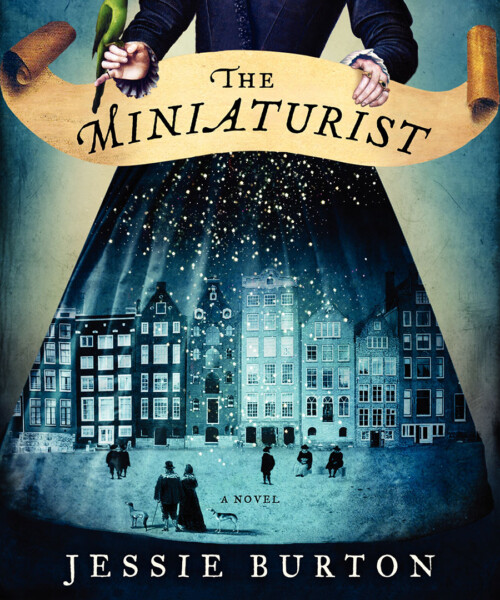

Five years ago, frustrated with her acting career, Oxford-educated Jessie Burton decided it was time to try a novel. She was drawn to the sight of an intricate 17th century dollhouse in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum owned by the wife of a wealthy merchant, and she began to imagine that young woman’s world.

The result is The Miniaturist, now outselling J.K. Rowling in Burton’s native England. The 32-year-old author is on a book tour across North America, where her novel, set in 1680s Amsterdam, is equally celebrated. In its review of Burton’s “accomplished first novel,” the Washington Post praised “a deftly plotted mystery, a feminist coming-of-age drama and a probing investigation of marriage.”

In the midst of her tour, Burton talked to DuJour about the inspiration, ideas, and at times unsettling parallels of her first novel.

When you consider Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Amsterdam definitely seems to be having a moment. But I think it’s so interesting that you didn’t set your sights on 17th century Amsterdam society and create a story. You discovered a story and then found a society.

Yes, that’s a perfect way of putting it. No, I didn’t have any particular fascination with 17th century Holland. I always liked the paintings, the still lives. They were so beautifully executed. I suppose we all remember “The Girl With the Pearl Earring.” There’s something appealing about that idea of harmony and symmetry and domestic peace. But I quickly found that underneath there was a much more complicated situation.

I keep thinking about the parallels between the acquisitive culture in your novel and those you would find today in New York City, London, Paris and so on. Did you think about that while you were writing?

Not until I’d finished it and it was being read by other people did it become obvious that 500 odd years later there are similarities to our post-free-market capitalist society. Money talks and yet God hovers. It’s a strange contradiction—and hypocrisy abounds.

Is there a parallel between a wealthy married woman then and now and that impulse to fill your home with things that help you feel as if you are in control?

Well I don’t know any of these women myself so I wouldn’t want to speak for them. But from a speculative position, sometimes I think women who haven’t gotten agency in other ways go inward and concern themselves with the domestic sanctuary. It’s where they stay, and many of them are happy to do so.

I gather that you entered the world of miniatures to research this novel. It’s a massive market.

Yeah, definitely. There is huge interest in it, where you have people with a whole room in their house dedicated to a village. They have the houses, and a church, and a post office, and a railway line. You know, I did find that slightly odd. I just thought, “Why?” and I don’t think they could’ve answered why. And then you have the sort of higher-end box rooms where you have one room at a very high price. Sort of this Chippendale furniture, sets of porcelain, and they’re kind of wish boxes. People commission them because they could never afford them in real life. Sometimes I couldn’t tell if people were talking about their real house or their doll’s house and that was weird.

How much time did you spend doing that part of your research?

I went to the Kensington Dollhouse festival twice. The first time I just wandered, and the second time, I got the courage to speak to miniaturists and sort of find out why they were doing it. A lot of them were very skilled craftspeople surfing the market. We have this relationship with small things. The thing is, the objects retain their essence. The volume is different, but the relative scale is exactly the same. Yet, they’re smaller and that’s what’s strange. We imbue the dollhouses with memory or we imbue them with power, and yet, we can never get into them, so it’s really strange.

I know you are crazed with your book tour but are you finding time to read anything for pleasure?

I’m reading three books. The Secret Place, by Tana French. Pacy, it is a suspenseful boarding-school murder. And Outline,by Rachel Cusk. Thoughtful prose with a streak of melancholy. With The Woman Upstairs, by Claire Messud, you have a bold and clever narrator, whose story seems ominous.

Nancy Bilyeau, the executive editor of DuJour, is the author of an award-winning trilogy of novels set in 16th century England.

MORE:

Where Deborah Harkness Gets Ideas for Her Suspenseful Books

4 Must-Read Page Turners Inspired by the Past

Summer’s Hottest Fiction Reads