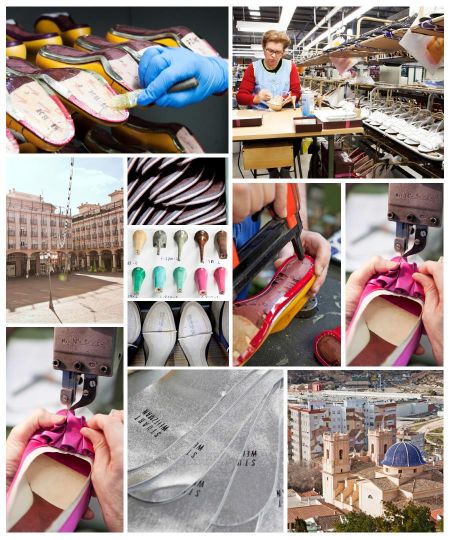

When Stuart Weitzman walks through the narrow streets of Elda, Spain, he’s treated like royalty. The sentiment is fitting: He owns four shoe factories in the town, and he jokingly refers to the area where they’re located—all within walking distance of one another—as “Stuart’s little kingdom.” But whereas the 71-year-old luxury-footwear veteran means this mostly as a bon mot designed to deflect the significance of his role there, the 3,000 people he employs—more than 35 percent of the town’s shoe-industry workers—might take it more to heart. He’s something of a one-man bailout plan for the Alicante region, where his base of operations has been for more than 30 years, producing loafers, boots, pumps and flats favored by everyone from Kate Middleton to the brand’s current poster girl, Kate Moss.

When Stuart Weitzman walks through the narrow streets of Elda, Spain, he’s treated like royalty. The sentiment is fitting: He owns four shoe factories in the town, and he jokingly refers to the area where they’re located—all within walking distance of one another—as “Stuart’s little kingdom.” But whereas the 71-year-old luxury-footwear veteran means this mostly as a bon mot designed to deflect the significance of his role there, the 3,000 people he employs—more than 35 percent of the town’s shoe-industry workers—might take it more to heart. He’s something of a one-man bailout plan for the Alicante region, where his base of operations has been for more than 30 years, producing loafers, boots, pumps and flats favored by everyone from Kate Middleton to the brand’s current poster girl, Kate Moss.

Weitzman spends more than six months of every year in Elda, which sits just inland from the Mediterranean port of Alicante (and boasts one of the best fish restaurants in the country). About his earliest days manufacturing shoes in Spain, beginning in 1971, while Francisco Franco was still in charge, “I started out in a dictatorship that was really repressive for the people, and now it’s this glowing democracy. I started to build factories, so once you do that, you really plant the trees; you’re not going to leave.” Each of his factories specializes in a certain kind of shoe. “I could have cheated and tried to make an evening shoe where they make moccasins, but they don’t have the hands for that,” says Weitzman, who tends to transmute old-school diligence into the language of necessity. “So every time I wanted to add something to the line, I had to build a new factory.” In work-scarce Spain, Weitzman shoemaking has become a lifeline for underemployed families, who sometimes pass down jobs through generations.

In fact, shoemaking was the Weitzman family business, too. Growing up, Weitzman apprenticed for his father’s footwear company, Seymour Shoes, based in Haverhill, Massachusetts, a mill town nicknamed Queen Slipper City. He and his brother took over the business in 1965 after their father died and right away they experienced the kind of shock and turbulence that’s still rocking manufacturing in the U.S.

“I wanted to make shoes, and it [costs] millions to set up factories,” says the Queens native. “I had to find someplace where I could start something.” So in 1971, when he was 29, Weitzman began searching for the best place to start over, figuring he would partner with an existing company until he had the resources to start his own.

He flew first to Italy, famous for its leather and luxury goods, but encountered a strike on the national train system and another strike at his hotel. Next he visited Spain, which has a sturdy, centuries-old tradition of shoemaking. “In Spain they did anything I asked for,” recalls Weitzman, whose self-named company has since become one of the best-loved high-end shoe brands in the world. “They worked during the lunch hour to show me how they made a product, and I thought, I can’t put up with the Italian system.” He signed on with the Spanish company Caressa, at first designing shoes under the label’s name and later creating a line with his name attached to the brand: Stuart Weitzman for Martinique. “I created a mini brand name at their expense but with my work,” says Weitzman, an adept businessman with a degree from Wharton. In 1986 he severed ties with Caressa. But by then he’d grown to love Spain, so he decided to stay.

Given his celebrity status—last November, he was presented with Footwear News’ Lifetime Achievement Award by Weitzman enthusiast Beyoncé—it’s impressive how intimately involved he remains with the production of his shoes. (When I visit him at his Manhattan showroom, I find him appraising the fit of a boot, sketches for future designs splashed around him on a desk.) He does the creative work of drawing and designing shoes in Spain, where he collaborates with two designers to produce patterns that they tweak until they’re good enough to make into samples. He has a knack for identifying on sight how a toe box or heel could be improved (comfort is his highest priority, if not something of a trademark).

Today, Spain’s manufacturing—an especially hard-hit sector of its battered economy—is facing enormous difficulty. But the shoemaker is well equipped to adjust to his circumstances. Elda is glutted with many shoe factories, but most operate on a contract basis for other big-name brands. (At the moment, he tells me, “all the espadrilles are being made there: Armani, Chanel, they’re all there.”) Few have permanent facilities in the region—and none has made the kind of powerful economic impact Weitzman has.

In the countryside surrounding his footwear fiefdom, Weitzman’s name is prefaced with the honorific Don, a title given to him in 2007, when he was named el Hijo Predilecto Adoptivo de Elda by the communities of Elda, Petrel and Rio Vinalopo (translation: favorite adopted son of Elda). He’s the only non-Spaniard ever to receive the honor. “It was the workers who nominated me, which made it very special,” says Weitzman, who is fluent in Spanish. Ever the entrepreneur, he prefers to focus on numerical motivations, but he’s clearly deeply touched by the accolade: “It’s the fact that they appreciate that they have been working in a good company. And I appreciate that they stayed with me.” Indeed, the average number of years people work for Weitzman is an astounding 22.

“I have no complaints,” he says. “Shoes have brought me a lot of fun in life—a lot of recognition but also a lot of pleasure.”