How old does a country have to be to have its own cuisine? For the nation of Israel, it looks like six decades or so was the magic number. As the country marks its 65th birthday, its serious foodie scene is accelerating. The micro-cuisine here melds Middle Eastern, Russian, Eastern European, Mediterranean and Jewish food influences to make something new.

London Chef Yotam Ottolenghi’s Jerusalem: The Cookbook is a New York Times Bestseller. New Orleans star chef John Besh is just one of a contingent of Americans who’ve toured the country in recent years in chef exchanges (He made jambalaya). In the past two years, two Israel-born chefs were nominated for James Beard Foundation “Best Chef” awards (Michael Solomonov of Philadelphia’s Zahav restaurant, for the Mid-Atlantic, and Alon Shaya, in New Orleans, for best Southern Chef.)

On any given Saturday night, Israelists are talking as passionately about food as any Brookyn hipsters waiting two hours for Thai. A variety of factors combined to make this happen. The farm-to-table movement was well-suited to Israel’s kibbutz history and ethos; genetic improvements in seeds to make them hardier in hot climates have aided the nation’s agriculture industry. Many eateries are kosher, and the restrictions have made chefs more creative. Lastly, the culture, particularly in Tel Aviv, is very youth- and gay-friendly, and going out to dinner is considered something of a party experience.

Chef Asaf Granit of Mahneyuda (which Fodor’s called perhaps the best restaurant in the country) in Jerusalem says the eating scene has changed radically as agriculture and imports have in recent years. A few years ago, “if you wanted to get truffles, you had to fly to Italy and put them into your suitcase,” said Granit, who named his restaurant after the city’s huge open-air market nearby. (Not that he ever did that.) “Now there is more seafood, pork, vegetables and olive oil.” (The flavor trade goes the other way, too: U.S. imports of Israeli juices, nuts, teas, spices, wine and beverages about doubled between 2007 and 2011, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.) With the greater availability of ingredients, Granit gets experimental: items on his cult menu include “liver pate with salty caramel” and “fish & pickles Israeli.”

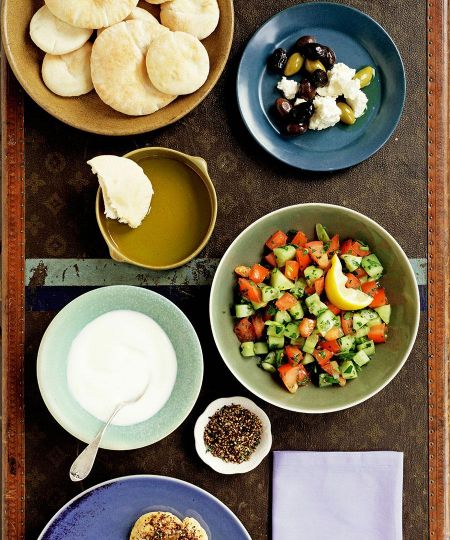

The brash nature of Israeli cuisine is evident first thing in the morning, where it’s often grilled beets and vegetables for breakfast. At the new Mamilla Hotel in Jerusalem, built by Moshe Safdie and designed by Piero Lissoni, there are 18 cheeses at the breakfast buffet, and the salty Bulgarian is paired with sweet watermelon, a national specialty. Lunch for locals is often falafel in the Old City, or Hummus in Jaffa; snacks are nuts and spiced nut candies. But it’s at dinner it’s where the nation’s crazy-quilt shows: the standard restaurant will have the same makes-no-sense menu variety of a New York diner: couscous, gyros, goose liver and spaghetti would not be unusual mix of entrees.

Consider the tony Scala, a kosher restaurant that sounds French-Italian in the David Citadel Hotel, where Hilary Clinton has stayed on diplomatic visits. Chef Oren Yerushalmi, who has worked at wd-50 and Café Bouley in New York, says first there’s the “challenge of making it kosher,” he says, then there’s the presentation. In Israeli fine-dining, the plates are less composed, he brags, “it’s not about the {beautiful arrangement of ] five things on a plate. It’s about the tastes.”

What’s next? Says Chef Granit, “Now people see you can make it, there’s more opportunities” for restaurateurs in Israel. The future will bring even more experimentation. “After 50 years or so, you don’t have to be so serious.”