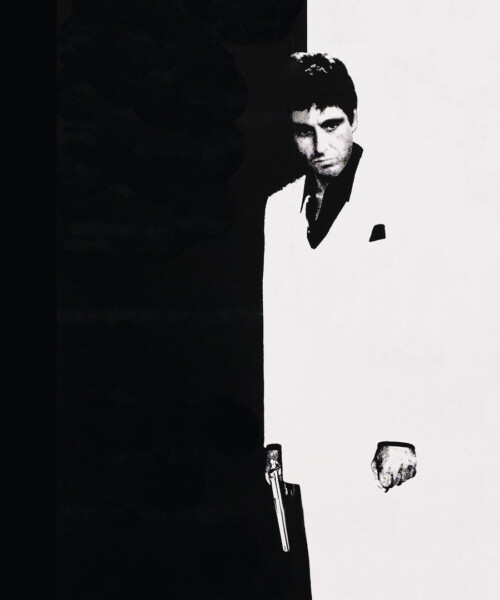

No matter where Al Pacino goes, he hears it. It could be New York City, Paris or Tel Aviv, but when he is spotted on the street, total strangers bellow lines from a movie released in 1983: Scarface. “Say hello to my leetle friend,” they yell. Or, “I always tell the truth—even when I lie.” Pacino is the star of more than 40 films and has been nominated for eight Academy Awards, but the role for which he is best known around the world, the performance that is perhaps the most imitated in the history of film, is still Tony “Scarface” Montana, Cuban refugee turned Miami drug lord.

And Pacino is fine with that.

“I always knew there was a pulse in Scarface that kept it beating,” he says. For years, Pacino was one of the few who believed in the film. Scarface was released to mostly bad reviews and indifference from the industry and the public. It took 20 years for it to become one of the most-watched films of all time—beloved by rappers, bankers and college students alike. And for the next decade it stayed popular: Millions of DVD copies have been sold around the world. There are video games and limited-edition boxed sets. Tributes range from comic books and posters to serious works of nonfiction.

This year, as Scarface reaches its 30-year anniversary, there’s talk of a remake from Universal Pictures. But before anybody tries to reimagine the film, it’s time to reveal what took place behind the scenes of the making of Pacino’s movie: the reversals of fortune, fears, rivalries, shouting matches and poor treatment of women that mirrored what would appear on the big screen. For all the turmoil, a powerful story emerged in Scarface, one that struck a deeper chord in society than almost any other piece of pop culture.

* * * *

Al Pacino as Tony Montana in Scarface

When Al Pacino was growing up in the South Bronx during the 1940s, his grandfather often talked about Howard Hawks’ violent gangster classic Scarface. Paul Muni played the part of a brutal, vicious Italian immigrant hood bearing a scar who prowled the streets of Chicago with a machine gun cradled in his arms and rose to the top of the bootleg-liquor business at the height of Prohibition.

Pacino never forgot his grandfather’s description of Scarface, but he didn’t actually see the 1932 movie until he caught it at a Los Angeles revival house in 1974.

“It was the first time in my life that I was blown away by a performance,” the actor says. “It was almost—uplifting.”

Pacino phoned his friend and former manager Martin Bregman in New York City and told him they had to remake Scarface.

Bregman, who had produced two of Pacino’s most memorable hits, Dog Day Afternoon and Serpico, had, by an odd quirk of fate, just seen Hawks’ Scarface on late-night TV and independently decided it would be “a great part for Al to play—the rise and fall of an American gangster,” he says. “I realized what Al could bring to it. He’d never had the chance to express that steely, streetwise quality he had. Even in The Godfather he was inscrutable—a rich man’s son, not a street gangster like Scarface.”

When it came time to find a screenwriter, Bregman approached Oliver Stone, who was not that interested at first. He didn’t want to write a gangster remake or deal with Prohibition. But Stone was, as he put it, “in a tough place.” According to Bregman, Stone took the assignment because he needed the money.

After Dog Day Afternoon’s Sidney Lumet agreed to direct, Stone got more excited, especially when Lumet suggested setting the remake in present-day Miami and transforming the character of Scarface into a Cuban refugee.

In 1980 the Marielitos were in the news. Following a tense diplomatic standoff with the United States, Cuba’s Fidel Castro opened the port of Mariel to anyone who wanted to leave. Within months, 125,000 Cubans landed in South Florida, crammed into some 3,000 boats. It soon became clear that Castro had forced boat owners to carry with them not just decent, hardworking Cuban families but thousands of “undesirables.” About 25,000 Marielitos had criminal records.

Stone was edgy and hyper, a shaggy-haired Yale dropout and Vietnam vet, a workaholic who by his own admission was pretty “drugged up.” In 1979 his screenplay for Midnight Express had won an Oscar, and for a while he’d been “like on a magic carpet,” living intensely all the fantasies he’d ever heard about Hollywood partying.

Stone stayed in Florida for weeks, getting to know both sides of the drug trade, law enforcement and gangsters. He met street hustlers—the men and women, mostly Colombian, who peddled drugs on the sandy beaches near the Fontainebleau hotel—and so-called banditos who unloaded cargo off the various Keys.

He took copious notes and came up with sketches for some pretty nasty characters, like “Omar,” an acne-scarred creep and coke-head, and “Lopez,” a half-Hispanic, half-Jewish hood who had become one of the richest and most powerful drug lords in Miami. Both would figure prominently in the script, as would a paunchy, corrupt cop. Not to mention some powerful South American families that manufactured cocaine.

Soon Bregman joined Stone in Miami and accompanied him when he went to speak to the authorities. “I was absolutely stunned,” Bregman says. He had assumed the drug business was big, “but when the U.S. attorney general told us cocaine was a hundred-billion-dollar-a-year industry, I thought I hadn’t heard right. ‘One hundred million dollars?’ I repeated. ‘No,’ he corrected me. ‘One hundred billion.’ ”

NEXT: “I wrote all of Scarface as a farewell to drugs, really.”