When Sophia Friendly opened the door to her killer, she was dressed for dinner.

It was October 12, 1978. In Palm Springs, California, a resort-home destination for presidents and entertainers—where Elvis and Priscilla honeymooned, where everyone from Frank Sinatra to Liberace held court—dressing for dinner was the protocol observed in many of the houses nestled in the desert valley. Sophia, age 71, donned a floor-length dress and gold shoes. Her husband, Ed Friendly, 74, put on a jacket. The couple’s maid set the dining-room table with crystal and a six-piece silver service that included slender fish knives.

At about 7 p.m. the killer walked in the front door of the three-bedroom Mediterranean-style villa at 893 Camino Del Sur. Something happened—words were spoken, a weapon revealed—and Sophia Friendly turned to flee down the hallway. She was shot in the back of the head and died instantly.

Frances Williams, the Friendlys’ 67-year-old cook and housekeeper, had just slipped a fish dinner into the warming oven. When the killer bore down on her in the kitchen, she dropped to her knees. A bullet to the head, fired point blank, ensured she died just as swiftly as her employer.

Ed Friendly wore a hearing aid. It is thought possible that, sitting in the bedroom, watching television and sipping a drink, he was unaware of the shots. He’d turned in his chair but had not risen to his feet when the killer struck a third time. Ed Friendly was shot twice—in the chest and in the head.

Photos and papers were tossed around, pants pockets turned inside out. Nothing was taken, including the $400 in cash in plain view in a wallet. But something was left behind: shell casings on the floor of the hallway, kitchen and den. Those casings would prove crucial but not for more than 30 years, after waves of police work drew tantalizingly close to an arrest time and again. The casings held the clues.

The killer did one thing more in the house on Camino Del Sur: A man’s fedora was tossed over the face of Sophia Friendly. It was as if to deliver the message that her death held the most meaning.

No neighbor observed anything out of the ordinary; no one heard gunshots. A car could have easily glided down the dim, quiet, palm-lined street unnoticed, the smell of dust and fig groves in the arid breeze.

It was the first triple homicide in the history of Palm Springs.

The next afternoon, Friday the 13th, Suzanne Friendly, a 36-year-old ABC network television producer in Houston, had just finished working on a commercial for Battle of the Network Stars when the phone rang in the editing room.

Suzanne remembers, “Both of the men that ran the company were there, and one man was going, Oh, no! He hung up and said to the other guy, who was the vice president, Do you want to take a walk with me?” Suzanne turned to her group of co-workers and said, “They probably have a problem with the promo for Battle of the Network Stars.”

The executives spoke in the hallway and then returned to the editing room. One of them, Jay Michaels, said to Suzanne, “We need to talk to you.”

She thought she’d made a mistake on the commercial reel, so she said, “Whatever it is, Jay, I can fix it.” Her boss guided her out of the room, touching her elbow, and cautioned, “I have some bad news for you. Your father.”

Ed Friendly had been scheduled for prostate surgery that day; his daughter, Suzanne, called him at home the previous night at 5 p.m. Houston time, to wish him luck, but no one answered the phone. “Oh my God, my father’s had a heart attack,” she said. And then, in a rush: “Oh please, don’t make me go down there. Let me do the show. My stepmother is—my stepmother is, you know, not a nice person. I just can’t be around her. She’ll be hysterical.”

“It’s your stepmother,” Suzanne’s employer said.

“My stepmother had a heart attack?” she responded.

“Well,” he said, and hesitated. “And the maid.”

“What are you telling me?” she asked, bewildered.

“They were all murdered.”

Suzanne Friendly remembers every word and gesture of how she was told of the deaths, but the rest of the day is a blur. She knows that she immediately flew to Los Angeles and was driven to Palm Springs, which is about 125 miles east. When she arrived, yellow crime-scene tape sealed the house. It wasn’t until the next day that she was permitted to enter and had the first of many conversations with police.

Suzanne learned that at 7:30 that Friday morning, the regular pool maintenance worker was beginning to clean the Friendlys’ pool when he noticed something eerily wrong through the window. What appeared to be a dead body lay in a pool of blood in the kitchen.

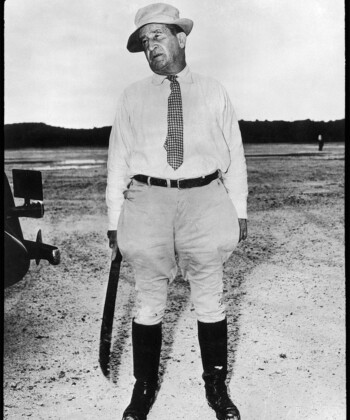

Ed and Suzanne Friendly

“It was a horrific murder scene,” says retired Palm Springs detective Tom Barton today, one of the scores of police who responded to the pool worker’s call. The Desert Sun reported that the three bodies were found in “grisly disarray” and that the warming oven containing their fish dinner was still on.

“I see them come and go, but everyone in this neighborhood pretty much keeps to themselves,” a neighbor was quoted. Others said they’d had cordial conversations with Ed Friendly about such problems as raccoons in the garbage. The Friendlys moved to Palm Springs in the early ’70s and bought the house in Vista Las Palmas in 1976.

Other than the shell casings ejected from the weapon, there was little if any physical evidence. Barton remembers that members of the local police department performed a three-block grid search looking for a weapon. Nothing.

It is axiomatic that the initial stage of a criminal investigation is crucial to solving a murder. The Riverside County District Attorney’s office took jurisdiction of the Friendly case. Police ruled out robbery as the motive. At first detectives focused on the background of Ed Friendly. His business ventures hadn’t always gone well. Ed came from a well-to-do family back East; his brother Alfred was the managing editor of The Washington Post. Ed was a realtor and a stockbroker. In California he was an executive at various racetracks, including one that burned down after he negotiated its sale. Maybe someone from one of Ed’s failed deals had a motive to come after him.

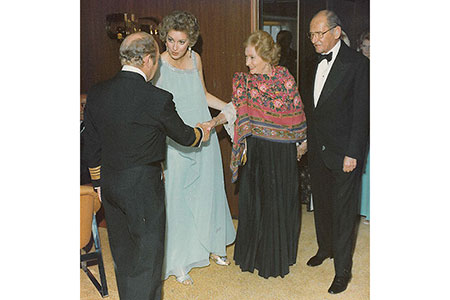

Sophia and Ed Friendly, on right, are greeted at a society function

But interviews with Suzanne Friendly led detectives to look more closely at her stepmother. Sophia Friendly, the former Sophia Brownell, belonged to San Francisco society and was on the city’s Social Register. Ed was her second husband. For 24 years she was married to Curtis Wood Hutton, a nephew of Edward and Franklyn Hutton—the founders of E.F. Hutton—and a first cousin to the famous Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, known in the press as the “poor little rich girl.” Sophia and Curtis had a son and daughter, Edward and Sophia, before divorcing. Police were very interested to learn there was bad blood between Sophia and her children. The acrimony was about money. There were accusations. A lawsuit. Estrangement.

Further investigation revealed the existence of inherited money. According to conversations with family members, Sophia Friendly was the beneficiary of multigenerational trust funds. Sophia’s ex-husband, Curtis Hutton, was the beneficiary of a $1 million trust fund awarded to him years earlier by Barbara Hutton, who considered him a favorite cousin. But there was a twist to the trust: If Curtis preceded her in death, Sophia would receive the money, not the children. Curtis’s son and daughter would inherit only if their mother died before their father.

NEXT: “Something upped the ante from grudges and tensions to a pistol fired…”