There was more. Curtis Hutton, it seems, was terminally ill, so the matter of who died first was critically important to the inheritance. About three weeks prior to the murder of the Friendlys and their maid, the weakened Curtis had visitors in his home in Santa Barbara, California: his 39-year-old son, Edward, and a friend of Edward’s named Andreas Christensen. It was well known that Edward Hutton was under severe financial strain: stalled career, a bad divorce, mounting debts.

And while Edward visited with his father, he talked about guns.

Fortunes carved out long ago quite possibly set the stage for the tragedy on Camino Del Sur. They were quintessentially American fortunes, forged by people of determination, on the West Coast and the East. Many upper-crust descendants contend with divorce, neglect, infidelity and failure—even suicide. But hundreds of hours of interviews with members of the Hutton and Friendly families, with their friends and employees, and with police officers and forensics experts in three countries, reveal a lethal level of dysfunction. Something upped the ante from grudges and tensions to a pistol fired into the brains of three helpless old people.

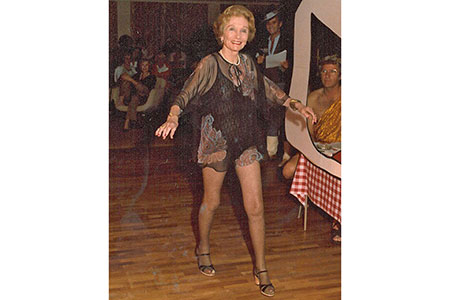

Sophia Friendly

Sophia Friendly, most likely the key to the triple murders, was the daughter of a respected San Francisco doctor, Edward Earle Brownell. Her inherited wealth came through her mother’s family, the Talbots.

Sophia was a descendant of Frederic Talbot, a true pioneer. On December 1, 1849, he arrived in San Francisco with his partner, Andrew Jackson Pope, by sea. They’d left their homes in East Machias, Maine, 51 days earlier, taking the harrowing route around Cape Horn. They were immune to gold fever, at its height, but alert to other opportunities created by vast natural resources and an influx of people. Talbot and Pope started a barge company and then moved into lumber. The partners purchased land in Oregon and built a mill on Puget Sound. Business exploded, with the lumber shipped to Japan, Australia, South America, China, Korea and Africa. By 1881, Pope and Talbot owned four sawmills, 19 ships and thousands of forested acres in the Pacific Northwest and Maine.

Sophia’s mother was a wealthy and socially prominent San Francisco matron who made sure her daughter had a brilliant society debut in 1924. A dainty and pretty copper-haired girl, Sophia wanted to be an actress and moved to New York City in her early twenties. She didn’t find a theatrical career. But she did find Curtis Hutton, nephew of the founders of E.F. Hutton.

The Hutton siblings were Edward Francis (E.F.), Franklyn Laws and Grace. E.F. and Franklyn achieved a tremendous amount through sheer hard work on Wall Street. But they were also catapulted to the American stratosphere of East Coast society by marrying heiresses.

E.F. Hutton, who dropped out of school and worked in the mailroom of a securities firm at age 17, married Marjorie Merriweather Post. She was the only child of C.W. Post, the Midwesterner with chronic stomach problems who turned his idea for a cold breakfast cereal into the behemoth named General Foods. E.F. Hutton and Marjorie entertained widely and built some of the most spectacular houses in America, including Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, which was declared a National Landmark (Donald Trump bought it in 1985).

E.F. Hutton and his second wife, heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post

This would appear a hard marriage to top, but Franklyn Hutton seemed to have done that when he wed 20-year-old Edna Woolworth, one of three daughters of Frank Winfield Woolworth. F.W., as he was known, started out with $300 and two five-cent stores: one in Utica, New York, and the other in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. By 1911, the F.W. Woolworth Company had 596 stores; its owner had transformed American retail. Woolworth is credited with being the first to buy merchandise direct from the manufacturers and then set the prices himself; he also created self-service display cases so shoppers could look at goods without needing a salesperson. In 1913 he built the neo-Gothic Woolworth Building in Manhattan for $13.5 million—in cash—and it remained the tallest skyscraper in the world until 1930, when it was topped by the Chrysler Building.

When Franklyn met Edna, she was 17, shy and lovely. Their wedding was at the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest on Fifth Avenue and 90th Street. Edna and Franklyn Hutton later moved into a fifth-floor suite at the Plaza Hotel. Their only child, Barbara, was born on November 14, 1912. But the marriage foundered. Barbara wrote of her mother many years later: “Like several other frustrated wives of the Plaza, she became a sad regular at the hotel bar, draping herself over the railing and asking the bartender in too loud a voice to guess when her husband had last slept with her.” Amid rumors of Hutton’s adultery, Edna, 27, was found dead on the floor of her Plaza suite, wearing a white lace dress embroidered with gold irises and a double strand of pearls. Some say a maid found the body; others that it was 5-year-old Barbara.

The New York Times reported, “According to New York City Coroner David Feinberg, who later asserted that an autopsy was unnecessary, death was due to a chronic ear disease.” The truth, according to biographies of Barbara Hutton, was that Edna Woolworth Hutton took a fatal dose of strychnine and her father paid the coroner’s office to cover it up. When a reporter later asked to see the files of the case, the coroner’s office said they had been “misplaced.” Those files were never found.

But what to do with little Barbara Hutton? At first she was placed with her grandparents, who lived in a 62-room Italian Renaissance mansion in Glen Cove, Long Island, and employed an army of servants, including 70 full-time gardeners. But F.W. died, and his widow, Jennie, was in the throes of dementia. Barbara was shipped off to live with her aunt Grace Hutton Wood in Altadena, a suburb of Los Angeles. Barbara’s father later had them moved to a large estate in Burlingame, on the San Francisco peninsula. He saw little of her, although he carefully guarded and invested her fortune. By the time she turned 21, her father had reportedly increased her fortune to $24 million ($754 million in today’s dollars).

Barbara Hutton, the heiress to a fortune, watches a tennis match in Palm Beach, Florida. She married Cary Grant two years after this picture was taken.

Barbara Hutton would squander that fortune, marry seven times (including to Cary Grant) and struggle with both addiction and the strain of being followed everywhere by reporters. It is said that when she died she had just $3,500 left. Barbara was famously—almost pathologically—generous, showering acquaintances with gifts. There were few people she was close to, but one of them is said to have been her older cousin Curtis, son of Grace. He was kind to the withdrawn and lonely girl.

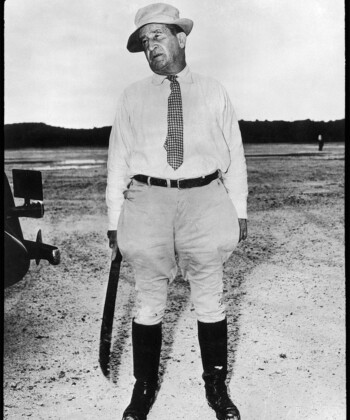

Curtis’s father, Benjamin Wood, did not stay married to Grace Hutton very long; years after the divorce, Curtis switched his middle and last names and became Curtis Wood Hutton. He was a sportsman, good at polo, and worked briefly as a stuntman in Hollywood. Later he moved to the East Coast, where he met Sophia Brownell.

After Curtis and Sophia were married, Barbara Hutton gave her cousin the $1 million trust. The trust income went to Curtis throughout his lifetime; when he died it would be liquidated and paid out to his children. Curtis bought a ranch near Santa Barbara and lived quietly with his family.

But in 1941, Curtis, then 41 years old, wanted to serve his country in World War II. Sophia would agree to his enlisting only if her husband signed an irrevocable agreement that, upon his death, the Barbara Hutton Trust income would go to her so she could support herself and their children. If she pre-deceased him, the original inheritance would stand and the children would inherit. Curtis agreed, and the clause was signed on January 9, 1942.

A portrait of Curtis Hutton in his World War II naval uniform

Despite Curtis’s coming back from the war alive, the agreement could not legally be changed. This might not have caused a problem except for the fact that in 1951, Curtis and Sophia Hutton divorced.

According to relatives, Sophia was a distant mother who relied on nannies to take care of the children. Nonetheless, after the divorce, the two youngsters moved with their mother to San Francisco, to live in a townhouse at 2507 Broadway purchased by Curtis. The townhouse was in the children’s names, but Sophia had the right to dwell there for the rest of her life. Also helping out the family was Sophia’s mother, who some believed had a reported $12 million inherited fortune. (In 1953, Sophia married Ed Friendly, himself divorced and the father of Suzanne and Tony.)