In the outdoor garden of Salonplafond—a buzzy new addition to Vienna’s burgeoning restaurant scene—you’ll find pastel-painted Adirondack chairs scattered throughout the grass, string lights draped above wrought-iron dining tables and tattooed bartenders slinging lemongrass-infused Moscow mules to a crowd of young, beautiful patrons. Some sit at tables dressed with blue gingham napkins and pint-sized succulent planters; others sprawl out on picnic blankets, hand-rolling cigarettes in the golden glow of a mid-July sunset. It’s an impossibly hip atmosphere filled with impossibly hip people. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think you were in Brooklyn.

Vienna? Hip? It’s hardly the first word that comes to mind when describing the Imperial City, a place more commonly associated with aristocratic palaces, horse-drawn carriages and Mozart concerts than, well, “trendiness.” But lately, the city has been experiencing something of a modern reinvention—a comeback, so to speak. Not since the early 1930s, before the devastation of World War II, has Vienna felt this alive. It’s as if the city just woke up from a seven-decade slumber, looking and feeling fresher than ever. The contemporary art scene is booming, chic boutique hotels are popping up alongside dated heritage museums and restaurants are revamping the traditionally heavy, meat-centric cuisine. You won’t find Wiener schnitzel on Salonplafond’s menu, for instance, but you will find local Danube salmon garnished with hemp seeds and watermelon radishes. Even vegan restaurants—the crunchy-granola variety you’d expect from Venice Beach—are having a moment, serving vegetable-based interpretations of Austrian dishes. (Incidentally, chanterelle mushroom goulash is even better than the real thing.)

Salonplafond, which opened just six months ago, is already a hotspot for locals and tourists alike. Come wintertime, the crowds move to the restaurant’s indoor space, where graffiti art hangs on the walls and DJs spin late into the night. What makes the eatery so of-the-moment isn’t the celebrity chef at the helm (Germany’s famed cooking-show personality Tim Mälzer) or the cozy, tavern-inspired aesthetic—it’s Salonplafond’s location inside the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), a historic space that has housed works of art, design and architecture for more than 150 years. Like the restaurant, MAK effortlessly fuses old and new: There’s an entire hall dedicated to Baroque Rococo Classicism (think 18th-century porcelain cabinets and gilded bronze wall clocks) that the late American artist Donald Judd designed.

These days, in nearly every corner of the city, you’ll see the grandeur of Vienna’s past carefully juxtaposed with the present. At the 14-acre MuseumsQuartier art complex—located just outside of the Imperial Palace in the former stables commissioned by Emperor Charles VI—Baroque-style buildings are sandwiched between ultra-modern facades, like the minimalistic Mumok (Museum of Modern Art), an imposing cubic structure that houses Warhols and Lichtensteins. The cultural hub feels like a strange symphony honoring the city’s roots while looking toward its future. Beyond MuseumsQuartier (MQ to locals), there’s even more happening: Ai Weiwei just launched a massive installation that runs from July to November; Francesca Habsburg, a descendent of Austria’s royal Habsburg dynasty, owns a contemporary hall that hosts edgy exhibitors like Tracey Emin; each summer, an international squad of graffiti artists can be found painting the town during the Cash, Cans and Candy street art festival. Given that Vienna just earned the title of “world’s best city to live in” for the seventh year in a row—a designation based on socioenomic conditions and quality of life—it’s no wonder so many young creatives are flocking here.

Vienna has long been considered the cultural and intellectual core of Europe, and rightfully so: It’s where Mozart, Strauss and Beethoven composed some of their greatest masterpieces, where Freud developed his early theories of psychoanalysis and where Gustav Klimt popularized art noveau. But it has also, until recently, lacked the sex appeal of more alluring destinations, like Paris or Florence, written off by travelers as being too serious, too staid—the kind of place that seems suited for AARP tour groups snoring the night away at the philharmonic orchestra. Several years ago, the Vienna Tourist Board conducted extensive market research to gain a better understanding of how travelers perceived the city. After surveying 11,000 participants in key regions like the U.S., Germany, Italy, Japan and Russia, they discovered a singular sentiment: Most people said that Vienna was a place they’d like to see “someday,” but they felt no urgency to go anytime soon. In response, the tourist board launched a massive worldwide advertising campaign with a snazzy, updated logo and a powerful new slogan: “Vienna: Now or Never.” They set out to show travelers that the most exciting time to see Vienna is now. Indeed, they had a point.

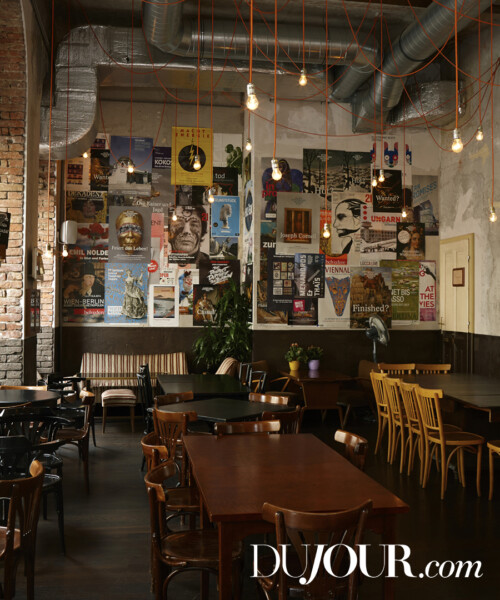

“Vienna has changed a lot over the past few years,” says Katharina Marginter, the owner of Das Möbel, an interior design shop located in the fashionable Naschmarkt neighborhood. The handcrafted contemporary pieces that fill Marginter’s tri-level space represent a portfolio of 250 established and emerging designers, more than half of whom are native Austrian. “The art scene is very lively and the creative scene is really thriving,” she says. “It’s younger, it’s greener, it’s more colorful now than it’s been in years.” Along with her interior design shop, Marginter owns Das Möbel Café down the street, which serves as a living showroom for many of the pieces; every item that furnishes the coffee house can be purchased on the spot. The café’s unique twist on Viennese coffee house culture—a tradition that’s recognized by UNESCO as part of Austria’s cultural heritage—is just one example of how the centuries-old custom is being reinterpreted. Though the stale, smoky institutions like Café Hawelka and Café Sperl will always have their place in Viennese history, fresh ideas are rapidly taking hold.

It’s just after 3 p.m. on a Tuesday in Wieden, Vienna’s latest cool-kid neighborhood, and the tattered armchairs at Vollpension have been occupied by locals for what seems like hours, a middle-of-the-workday Viennese phenomenon that Americans will never truly understand. Hipsters graze on avocado toast and field greens, and businessmen sip coffee while thumbing through the paper, as if they have nowhere in particular to be. Yes, the city is changing quickly—but inside coffee shops, time continues to stand still. Vollpension (“full pension”) is littered with antique vases, dusty table lamps, faded family portraits—a hodge-podge of tchotchkes that look like they’ve been plucked straight from grandma’s attic. And in fact, they have: The café is decorated and run entirely by senior citizens. It launched in 2012 as a temporary pop-up during Vienna Design Week, a citywide festival now in its 10th year, but the charming concept took off and Vollpension stayed put. Gaze past the tiled countertop into the kitchen, and you’ll see “Opas” (German for Grandpa) and “Omas” (Granny)—like 74-year-old Charlotte, a former chambermaid at the iconic Hotel Imperial—churning out secret family recipes for tartes, biscuits and cakes. On any given day, there are more than 200 varieties to choose from. The menu describes Vollpension as “an intergenerational coffee shop run by and for the old and the young” that aims to intermingle Vienna’s new generation with the old guard. It seems to be working.

In 2010, Austrian hotelier Florian Weitzer did the unthinkable: He voluntarily relinquished the five-star status that had been awarded to one of his properties, the Hotel Wiesler, located two hours outside of Vienna in Graz. He craved independence from the formality that required five-star hotels to have uniformed bellmen and stringent dress codes, and he was confident that a new wave of travelers felt the same. At that time, says Weitzer, “You could find a lot of imperial and traditional properties, but there was a lack of new and innovative hotel concepts in Vienna. We wanted to breathe new life into the hotel scene.” A year later, he did just that. Weitzer’s stylish boutique hotel Daniel Vienna opened in 2011, followed by the Grand Ferdinand in 2015, offering visitors a laid-back approach to luxury that the city hadn’t seen before. The properties have youthful elements, like Vespas for rent and in-room hammocks (Daniel) and a swanky rooftop pool (Grand Ferdinand), but also pay tribute to Vienna’s old-world glamour. Ornate Lobmeyr chandeliers hang in Ferdinand’s lobby, for instance, and the restaurant’s silverware comes from an Austrian silversmith that has been around since 1882. Weitzer’s hotels are a stark contrast to the Viennese institutions just across the street. At the Hotel Imperial, butlers iron the newspaper each morning to save guests from ink-stained fingers; the museum-esque Hotel Sacher feels like stepping back into another era, even though it’s now more “casual” (by Viennese standards) than when it opened in 1876. The dress code at Sacher’s stately Marble Hall has loosened (diners are no longer required to wear a jacket and tie), though its role as a stomping ground for aristocrats and high society endures. The style is shifting, but Vienna is by no means on the brink of becoming a watered-down version of its former self. If you walk past the Marble Hall dining room on any given night, you might see a table set for 60 with a seating chart that lists Prince Philipp and Princess Isabelle of Liechtenstein as the evening’s hosts.

“You see these tables?” says entrepreneur Florian Kaps, pointing to the cluster of well-worn bistro tables on the patio of his quirky concept shop in Vienna’s Praterstrasse neighborhood. “The Hotel Sacher thought they looked crappy, so they threw them out. But I love these! The marks that are here, they tell their own story. I only like to use things that have history.” Kaps and his co-founder Andreas Eduard Hoeller, both native Austrians, opened their store SuperSense on the ground floor of an abandoned 19th-century palace two years ago. The sprawling space contains a café, recording studio, retail store and a “scent laboratory” for creating custom fragrances. “It took the older people in the neighborhood quite some time to understand it,” says Hoeller. “Initially, the first three weeks or so, people didn’t dare to walk in. They’d stand in the entrance and ask, ‘Is this a museum? Can we enter?’ There was a bit of a novelty in the beginning, but now people are so comfortable here, sometimes it’s difficult to get them out!” It soon became clear to Hoeller and Kaps that SuperSense was exactly what Praterstrasse needed. “People weren’t going out anymore because there was nothing to do. They felt like the neighborhood was missing something,” explains Hoeller. The once-posh boulevard, which spent the better part of the 20th century in decline, is slowly returning to its former glory. Hoeller and Kaps seem to have a knack for recognizing potential. Prior to SuperSense, they made a small fortune by launching The Impossible Project, a company that saved instant film from “extinction.” When Polaroid announced it would be permanently shutting down its last factory in 2008, the duo bought the production machinery for $3.1 million and started manufacturing cameras and film themselves. The Impossible Project’s product line is sold at SuperSense, as well as stores in 43 other countries, and has since amassed a cult following. “I’ve opened shops all over the world, but what’s special about Vienna—what makes it unlike anywhere else—is that you can still feel the glory of its past everywhere,” says Kaps. “We’re just hoping to give people who visit this city again a reason to discover something new.”