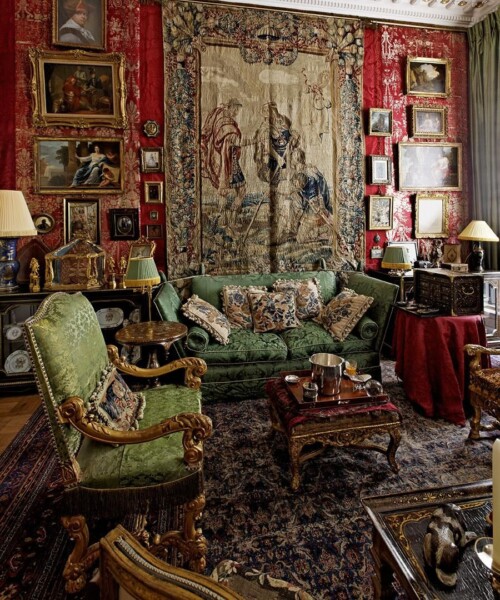

Antiques dealer Sylvain Lévy-Alban lives like royalty. Take the inlaid marble on the floor of a passage in his Paris apartment. “It’s Sicilian from the 18th century,” he says, “probably from a palace.” The tapestry in the sitting room of Emperor Constantine going into battle? “It’s 17th century; it belonged to Louis XIV.” And the footstool in the library? “That’s what the Duchess of Windsor used to put her feet upon.”

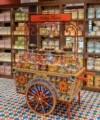

Lévy-Alban has no delusions of grandeur, however. If he suffers from anything, it’s a deep love of history. In his shop—a must-stop for designers like Penny Drue Baird, Michael S. Smith and Charlotte Moss—on the antiquarian-dense row of Quai Voltaire, he specializes in 17th-, 18th- and early 19th–century European furnishings and decorative objects. Why that period? “Because I like it,” he says. When questioned about his choices, that’s often his answer. But he’s not being elusive or difficult; his preferences are simply second nature to him. And while many people regard their most precious antiques as too valuable to handle, exiling them to climate-controlled cases, Lévy-Alban has sprung these treasured relics from the caste of untouchables and brought them to life once again in his home.

Located on a quiet street in the center of the city, behind the Palais Royal, his two-bedroom apartment, in a building constructed in 1778, has the soaring 15-foot ceilings and windows typical of the era. Lévy-Alban’s home is decorated in a way that flies riotously in the face of minimalism: It’s sumptuous, layered and full of vivid colors, rich textures and history. This exaggerated style has recently become associated with another Parisian, designer Jacques Garcia, he of the impeccable taste and high-profile projects. Garcia has created the opulent interiors for Manhattan’s NoMad hotel, Paris’ Hôtel Costes and La Mamounia in Marrakech. A book showcasing his personal pièce de résistance, the Château du Champ de Bataille in Normandy, will be published by Flammarion next year.

Garcia and Lévy-Alban have been friends for three decades, drawn together by their similar tastes in art and antiques. “Jacques is a good customer of mine,” adds Lévy-Alban, who purchased his apartment in 2010. Throughout its renovation and design, Garcia served as informal adviser and sounding board. “He gave me many ideas and many little drawings,” Lévy-Alban says. Lévy-Alban’s general goal was “to give the ambience of a Parisian home from the period [when it was built].” Every room is chockablock with stuff, and in the sitting room, dozens of 17th- and 18th-century oil paintings, ranging in size from a few square inches to a few square feet, line the walls. Rather than feeling like gaudy excess, the overall effect is luxurious and captivating. But how does he decide when too much is too much? “When you want to get out as soon as possible,” he says. “Sometimes I’m in people’s homes who’ve arranged things neatly, but the way they put them makes you want to run. There’s a complete lack of harmony.”

To achieve balance, he relied on intuition, adjusting the placement of items until everything felt just right. To cover the wall behind the tapestry, Lévy-Alban followed his instincts (and Garcia’s) and used two different 18th-century fabrics. “I didn’t have enough for [the entire wall], so Jacques said, ‘Mix them and it will look good.’ ” The red-and-gold material has an intriguing provenance: It hung in the bedroom of the famously fashionable Carlos de Beistegui. Doesn’t Lévy-Alban fear that light will destroy the rare cloth? “It will last as long as me. It will rot, and that’s it,” he says.

This attitude—that the things we cherish should be seen and used—is what makes his home so inviting. Nothing is off-limits, and you get the sense that life in Lévy-Alban’s apartment is to be lived and enjoyed. In the passage, he commissioned built-in closets and converted 18th-century Chinese lacquer panels to serve as their doors. Part of the facing wall is covered with a multipatterned fabric; it’s not an antique. “I like to mix things,” Lévy-Alban says. “I’m not obsessive.” The cloth was made by another aesthetically inclined friend, London designer Alidad.

In the dining room, Garcia’s influence can be seen in its color palette and in the Versailles-style mirrored doors (they’re purely decorative) that Lévy-Alban commissioned and placed in the corners to reflect the light and enlarge the space.

Since his apartment faces south, that room and the others are usually filled with light in the mornings, which was a draw for Lévy-Alban. But one of his favorite times of day is after the sun has set and he closes up his shop on the Left Bank, when he takes the 10-minute walk home, opens his door and steps into the peaceful world he’s created and filled with beloved objects from the past and present. “I feel happy,” he says. “I relax as soon as I arrive.”

Click through the gallery to see inside Lévy-Alban’s home.

MORE:

Inside Nicky Haslam’s Perfect English Country House

Miles Redd’s Most Fabulous Rooms

A Look Into the World’s Most Creative Work Spaces