If someone tells you to watch a film called A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, it is likely that within seconds you will have envisioned an egregious queue of horrors set to befall the girl in question. But the feature-length directorial debut of Ana Lily Amirpour is nothing if not divergent from expectation.

The film’s protagonist is actually far from helpless—at least in the conventional sense—since she turns out to be a vampire. Played by Sheila Vand (Argo, NBC’s State of Affairs), the eponymous “girl” glides around a desolate, crime-ridden Iranian town called Bad City, where she watches—and occasionally preys on—the town’s more depraved citizens. One night she wanders across a young man named Arash (played by Arash Mirandi), who is stalled under a lamppost dressed up as Dracula, having just come from a costume party where he’d taken too much ecstasy. The girl pushes him home on a skateboard, and a reticent romance is born.

While it is true that a vampire, and all the particular quandaries that come with being a vampire, color the core of Girl, the film is far from riding the overwrought fad that has spawned endless spinoffs. “I think it taps into things that are more universal,” Vand says, “like loneliness, love and boredom—and being an outsider.”

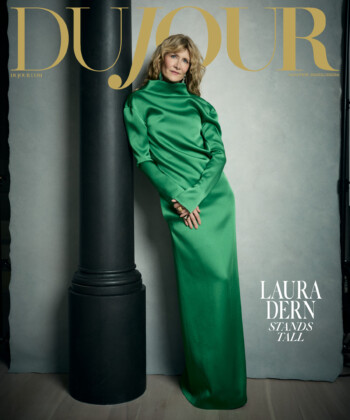

Sheila Vand

With its dreamy, high-contrast black and white cinematography and pointedly minimalist dialogue (all in Farsi), Girl made a weighty impression at Sundance this year. The film gestures to a unique collision of influences—Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns, David Lynch’s surrealism, Iranian New Wave Cinema, Tarantino—but the final product is clearly a distinctive and emboldened imagining on the part of its fledgling director.

Vand, who worked with Amirpour on a few shorts prior to starring in Girl, says of the director’s creative fervor, “She’s a true artist, so working with her is an extremely passionate, intense experience. She’s very specific about what she wants, and you kind of have to give yourself up and get lost in her world. I was just taken aback by how relentless she is—she has some pretty big artistic balls. She’s very creatively stubborn, which is what I think it takes to make anything great, because you’re up against so many different people trying to tell you how to make a movie.”

Vand says that the mental preparation for the film took about “ten times longer than the actual shoot,” and that for nine months they prepared by watching films and reading books, wriggling into the dark headspace of the dystopia Amirpour envisioned as Bad City. No detail was too small to warrant obsession. “As far as the character of the girl specifically,” Vand says, “she had me watch a lot of YouTube videos of snakes and cats and tigers because she wanted the girl to move in this animalistic, supernatural way—like hyper-alert but really slow… Something I really loved about the girl and that I tried to explore in my performance was a balance between being delicate and being dangerous. She really does ride that line. She always seems as if she could fall apart at any moment, but in reality she’s the predator—not the prey.”

Certainly the girl’s character is complex and much of her behavior seems to be written with the intention of resisting interpretation. Nonetheless, the gender-power dynamics in Girl are refreshing—especially among tales of the vampire-falls-in-love-with-

“Lily actually has a little bit of an aversion to the film being labeled ‘feminist,’ even if that quality is in there. But we didn’t set out to make a political movie about being an Iranian woman or anything like that. It was more that we wanted to make a film that we had never seen before, and would want to see. Honestly, it was more about just telling a love story.”