During her lifetime, heiress Doris Duke was known for her many romantic affairs, intense relationships with men ranging from General George S. Patton to Errol Flynn that blazed for a while before sputtering out. Today, one of her great passions—her love of Islamic art—lives on in the form of Shangri La, her estate in Hawaii that serves as a museum for her unrivaled collection.

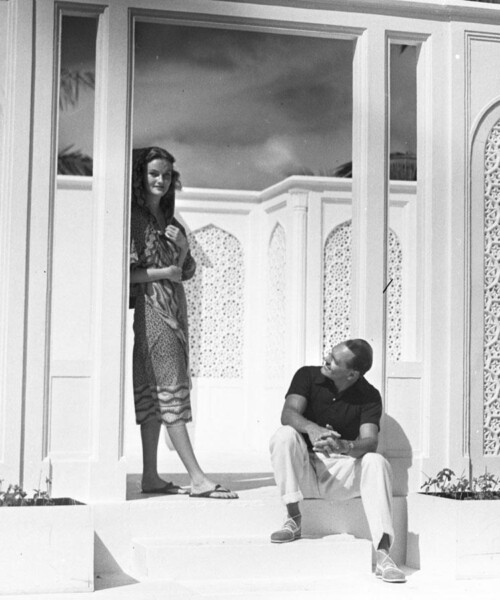

When tobacco and energy magnate J.B. Duke died in 1925, he left $50 million to his 12-year-old daughter, Doris, making her the “world’s richest girl.” She received the first major installment of the inheritance at age 21, then married James H.R. Cromwell at 22 and went on a 10-month honeymoon with him to Europe, Egypt, India (where they met with Gandhi), Indonesia, China and, finally, Hawaii. This trip led to Shangri La’s creation in two ways: Duke became captivated by the art of the Islamic world on her travels (she was particularly inspired by the Taj Mahal); and she also fell in love with Hawaii. The couple had planned to spend only a few weeks there but ended up staying for four months.

In 1936, she purchased five acres of land on Oahu near Honolulu’s Diamond Head. Work on the house began that year and was largely competed by 1938. During the construction process, the design of the home—consisting of multiple gardens, terraces and pools surrounding a white 14,000-square-foot main building—changed to reflect her evolving tastes and ideas and to best display her expanding collection of Islamic art. She continued amassing works until her death in 1993, and today Shangri La contains more than 2500 pieces which span the 7th to the 19th centuries. Her will established the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, and Shangri La was opened to the public in 2002.

“Doris Duke wasn’t just buying the best things on the market and incorporating them into a house. She acquired property and designed a home and estate that reflects her passion for many regions and cultures in the Islamic world—that’s what makes Shangri La so special,” explains Deborah Pope, Shangri La’s executive director since 2000. “She did it with such a great sense of aesthetics and such a strong sense of place. Another thing that makes Shangri La so unique is the unlikely marriage of historical and artistic tradition with very contemporary things like commissions and the basic modernism of the house.”

Because of its location far from the mainland, Shangri La is perhaps not as well known as Duke’s other estates in the U.S.: Rough Point in Newport, Rhode Island, and Duke Farms in Hillsborough, New Jersey. But a traveling exhibition “Doris Duke’s Shangri La: Architecture, Landscape and Islamic Art”—containing photographs by Tim Street-Porter and select pieces from the estate—and the publication of a companion book of photos should bring it to greater public awareness. The exhibit is at the Museum of Art and Design in New York City through Feb. 17, 2013, and then heads to Palm Beach, Florida. (The photos here are all from the book; the cover is shown, right.)

Even if you go to see the exhibit, you should still try to see Shangri La in person. For one thing, it’s a good excuse to visit Hawaii. But more importantly, Doris Duke’s island retreat must be experienced firsthand to fully appreciate its magic. “There is no substitute for standing in front of a 15-foot-tall ceramic tile mihrab, or prayer niche, from Iran. Every surface is covered in ornamental design and calligraphy, and because this piece is actually embedded in the building, it does not travel. But not just sight is involved in a visit to Shangri La,” Pope says. “You’ll be surrounded by the scents of jasmine and tiara gardenia in the Mughal Garden. You’ll hear the sounds of the fountains, the water cascades, the roar of the waves and the racket of the wild parrots as they come back to roost in the trees. Shangri La stimulates all your senses.”