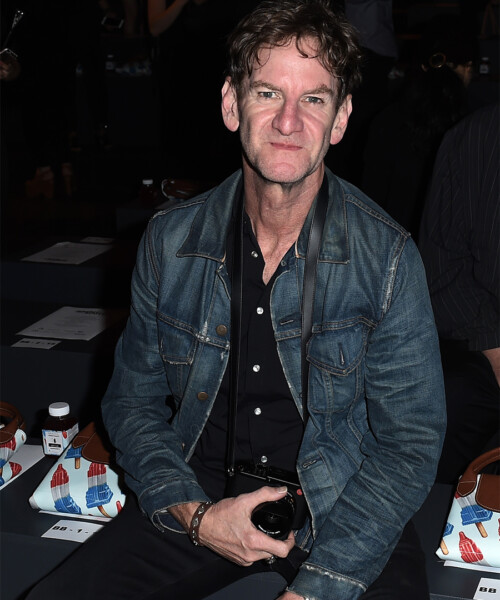

In certain quarters, you aren’t really someone until you’ve had your picture taken by Mark Seliger. The photographer made his name shooting rock stars for Rolling Stone and has gone on to capture heavyweights from the Dalai Lama to Barack Obama. To the casual observer, then, his most recent project, On Christopher Street, seems like a striking departure: It’s a book of portraits of trans- and genderqueer New Yorkers—few of them famous—who have long called Greenwich Village’s Christopher Street home.

But the project, three years in the making, is not as much of a deviation from Seliger’s celebrity work as it appears. A common philosophy, encapsulated in the Minor White quote above, permeates Seliger’s art: Be receptive, prioritize consent and strive to capture the subject’s essence. These principles, while great when shooting J—Law, become hugely important when documenting the unsung members of a marginalized community. Especially one that—despite the rise of celebrity avatars like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner—often remains stereotyped and misunderstood.

Seliger’s respect for his subject’s core is key to everything he does—including the way he writes, says graphologist Annette Poizner. “He carefully prints one letter at a time, honoring the form of each with great loyalty.” The photographer was careful to honor the multiplicity of ways his Christopher Street subjects presented themselves, too. “Their stories were so varied,” he says, “and it became so important to reflect that diversity of experience.” Especially because woven through that carefully rendered individuality was a common thread. “A lot of the stories—regardless of social class, race or group—included an element of hopelessness.” He adds, “And then the sky cleared once they knew they could do something about [reconciling their appearance with their true gender]. [With those stakes], you really feel you have to get it right.”

But how? Again, Seliger’s writing provides a clue. “Almost all of the samples I’ve analyzed have had a signature,” Poizner says. “This one doesn’t.” Seliger’s refusal to sign White’s quote mirrors his commitment to, as he says, “take myself out of the equation” when it comes to how his subjects are portrayed. Paradoxically, then, the real hallmark of a Seliger portrait—raw, stripped-down, intimate without ever prying—is a documentarian’s attempt at self-erasure.

Trans- or cisgendered, the stories Seliger wants to tell are someone else’s. Poizner suggests his all-capitals lettering is distancing, noting, “He’s not an easy man to get to know through his words.” Seliger isn’t easy to get to know through his photographs either. But that’s okay: His subjects are.

1. Putting a date [is] a sign of humility.

2. Children are instructed very specifically when to use capitals and when not. Some writers defy the rules; they show a strong independent-mindedness.

3. This spiral is a psychological symbol; it represents an inner essence which radiates outwards as he expresses himself.

4. He doesn’t give his signature. This is not an oversight.

Image credit: Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images