In the closing scene of Charles Bock’s 2008 debut novel Beautiful Children, we see an unkempt, tormented teenager scrabbling over desert sand dunes outside of Las Vegas in the dead of night, trying desperately to reverse an event that will sear itself onto his future identity, as he wonders: “Just what am I supposed to do now?”

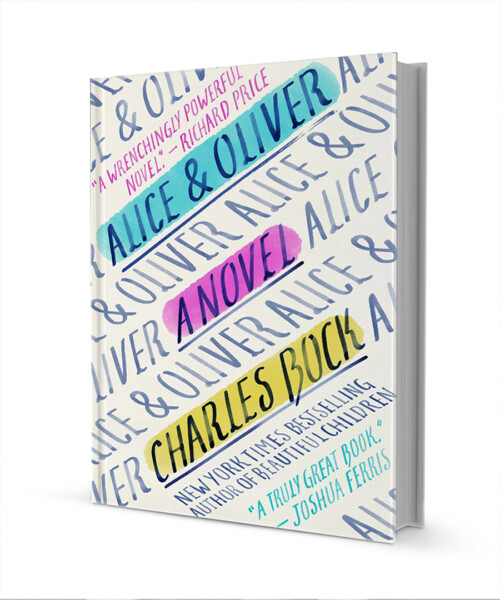

This March, ten years after Beautiful Children won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction and was named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, Bock brings us his second novel, Alice & Oliver—and that question of existential paralysis, once whispered into the desert darkness, is now shouted forcefully into life’s most definitive darkness: death. Based closely on the true story of Bock’s wife’s diagnosis with cancer four months after the birth of their first child, the novel accompanies Alice and Oliver, a young couple with a new baby living in New York in the 1990s, on their passage of treating the disease that will eventually kill her.

“A horrible thing happened,” Bock says. “Just a random terrible, terrible thing. What are we supposed to do? It doesn’t make sense and it’s not fair and there’s no key or answer or way through it. It’s just a perpetual, huge state of shock… But I very much wanted my daughter to understand what her mom went through to try and stick around—to keep being her mom. I also wanted it to be a real, excellent piece of writing.”

Readers familiar with Bock’s past work will find his prose now more spare and intimate, as he folds vivid, flawed and lovable characters into a hospital universe that is both clinically sterile and thick with humanity—porous within a Manhattan when the Meatpacking District still stank of pig guts and Alphabet City was a place you might take someone you’d like to see mugged for their shoes.

While there is much to admire in Alice & Oliver, from small flurries of arresting description to its blanket heartbreaking effect, perhaps its greatest triumph is that in facing the ultimate unanswerable tragedy, Bock seems to have finally found something like an answer to that incessant question: What are we supposed to do now?

“This book comes from a point of understanding,” he says. “We still have the moments we have. After a good friend of mine first heard me read from the book, he just said, ‘I’ve got to go. I just got to go home and tell my wife and my kids that I love them. I’ve got to go.’ And I think that… that’s about all I could ask.”