Resistance movements shape the societies they challenge, nowhere more than in the United States: The country’s entire narrative can be schematized as a series of transformative fights against “the Man,” starting with the American Revolution and culminating in today’s mass marches, with seminal battles for abolition, suffrage, civil rights, women’s rights, and queer rights stretched across the arc of our history. The irony inherent to countercultures, of course, is that when they succeed they stop being counter and instead become emblematic of their period’s political and societal discourse—in other words, of its popular culture. This evolution from fringe to front-and-center is at the heart of “Counter-Couture: Handmade Fashion in an American Counterculture,” at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design through August 20.

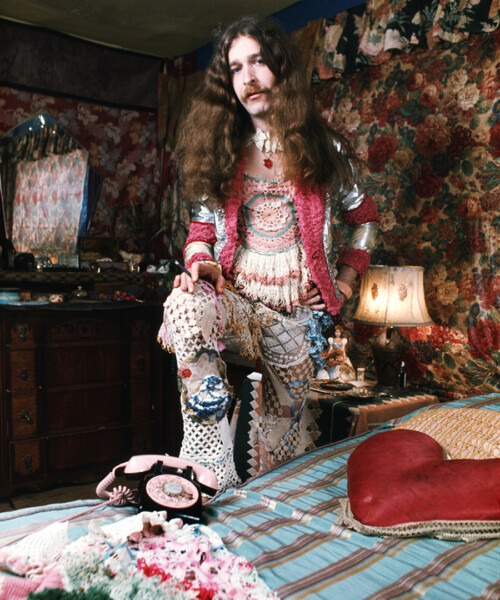

Costume designer Fayette Hauser, 1971

Photo by The Estate of Clay Geerdes

Revolutionaries have long used clothes to further the cause, from suffragettes’ willfully conventional white dresses to punks’ intentionally confrontational destruction-chic. But in staging the show, designer and guest curator Michael Cepress zeroed in on fashion’s pivotal role in the resistance movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, when—thanks in part to post-war affluence and the availability of mass-produced materials—how one dressed for the first time became a signifier of what one believed in. Rejecting the conformity and materialism of their parents’ generation, the free spirits of Haight-Ashbury and Greenwich Village hand-crafted a new identity, one centered on self-sufficiency and self-expression. Its descendents are everywhere, from the vapid (Coachella’s bougie-boho vibes) to the transformational (the collective action of a renaissant feminist movement). But its macramé and tie-dye remnants remain as well, buried in old trunks and musty attics.

“There’s the great surprise of how much of the actual clothing still exists, and how unnoticed and uncelebrated it’s been,” Cepress says. “It’s the most breathtaking wearable art imaginable, and in so many cases, the pieces are in the hands of folks who were convinced they were completely forgotten.”

Fashion designer and wearable art pioneer Kaisik Wong, 1974

Photo by Jerry Wainwright, 1974

Traveling the country to dig through strangers’ personal effects, Cepress unearthed singular artifacts, from embroidered denim and delicate crochet to handcrafted jewelry. “All of that color, that celebration of pattern, pushes against the darkness of everything that was [going on],” he says of the joyful garments born against the backdrop of Vietnam and the civil rights movement. “They’re smack-up opposed to [the sober, conservative lines] that were otherwise in fashion.”

The styles in glass cases bear an uncanny resemblance to those worn at today’s protests. (Counterculture or not, fashion is cyclical.) Curatorial assistant Barbara Gifford notes their “sense of humor, used to grab attention.” It’s a lesson taken to heart by the millions of women and men who marched the streets of America wearing bright pink pussy hats, grabbing back.

Main image: Richard “Scrumbly” Koldewyn, a leading light of hippie fashion, in his iconic doily suit, 1972

Photo by Jerry Wainwright, as pictured in native funk and flash