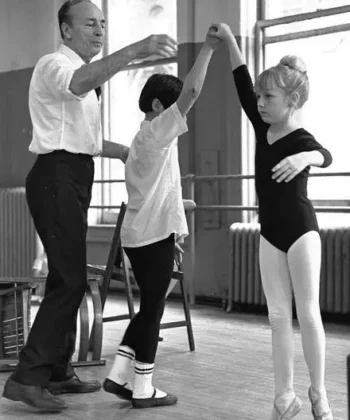

In the nebulous territory between fact and fiction—a dark wilderness we wander with increasing frequency—Sheila Nevins has long shone an unwavering light on the hardest of facts. At 78, Nevins has worked at HBO Documentary for nearly four decades (she’s been president there since 2004) during which she has produced over 1,000 films and won a staggering 26 Academy Awards. Lauded as a pioneer of the modern documentary, she’s been the force behind recent sensations like Citizenfour, Going Clear and The Jinx, and has individually won more primetime Emmys (32) than any one person in history.

So when Nevins finally sat down to write her memoir, she might have been expected to turn out something of a how-to manual for being the world’s most effectual human. Delightfully, she took a slightly different tack: “Why don’t I write about Teddy the hamster?” she says she asked herself one night, before drifting off to sleep. “Why don’t I write about a facelift? Why don’t I write about adultery? Why don’t I write about Viagra? People don’t talk about facelifts; people don’t talk about how old they are. So maybe I’ll be one of those people who does.” This statement suggests an honesty rarely heard from a woman of her accomplishments, but entirely in keeping with the truth-seeking work to which she’s devoted her career.

The result of her musings and remembrances is You Don’t Look Your Age . . . and Other Fairy Tales, a collection of personal essays, poems, fictionalized anecdotes, modern parables and vignettes that add up to a deeply warm, funny and sharp portrait of a woman who has lived a full life, and is finally ready to talk about it. Nevins writes candidly about her history: the anguished decision to go under the knife, her sexual misadventures with bosses as a young woman, a conversion from the wisdom of Helen Gurley Brown to the teachings of Gloria Steinem and her particular proclivity for faux pas. She describes a harrowing incident of pet dismemberment in which she pulls the tail off her son’s beloved (and her reviled) hamster, and writes a heartbreaking letter to the great aunt who died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. For more delicate topics she adopts the voices of other women, and in these personas she tells tales of adultery, struggles with weight loss, sleeping in separate bedrooms and addictions—stories of rich women who could never escape the poverty of their youths. “There were things I wanted to sort of slyly talk about, so I invented imaginary characters,” she says. “It’s a joyride because you’re going from one reality to another. . . . In the three hours it takes to read the book, it’s possible to go through a gamut of emotions and styles, and I wanted that because life takes you through a gamut of emotions and styles.”

You Don’t Look Your Age . . . and Other Fairy Tales

But throughout, the most persistent motif is the experience of growing older. Two years ago, Nevins produced a documentary about Nora Ephron called Everything Is Copy. In the film, Mike Nichols says of Ephron that, “In writing it funny, she won.” I couldn’t help but recall this sentiment when reading You Don’t Look Your Age—indeed, the subject of aging often finds Nevins at her funniest and most profound. And yet, there is the sense that while she wants dearly to accept the inevitable, she cannot quite. Even as she puts her affairs in order, the notion that she might have more to give before the curtains are drawn discernibly haunts her. She knows she has “won,” by all earthly standards, but Nevins didn’t get where she is by settling for standard.

Aside from questions of life and death, merely promoting the book has put Nevins—no doubt accustomed to being the intellectual authority in most rooms she enters—in some unusual positions. “You know,” she says, “I sometimes feel very trivial in light of what’s going on in the world today. I think the personal sphere always has a place, so I kind of justify it that way. But I did the Charlie Rose show, and I was sitting with these political pundits and everyone was talking about the French election, myself included. Then it was my turn to go on, and I felt like a cosmetologist or something, like I was selling mascara. Can you imagine? There were all these great pundits—and there I was talking about hamsters. It was like I was the court jester. Here I am fighting for women’s rights, the world is falling apart, and I’m talking about getting old on 42nd street. ‘I’m in my underwear here,’ I thought. ‘This is despicable, they should ask me to leave!’ It was horrifying.”

But of course it wasn’t, and if anyone’s earned a hall pass to wax poetic on the joys of Xanax and the woes of never-ending dental work, it’s Nevins. In a strange way, You Don’t Look Your Age feels like a gift in this particular moment because of its attention to the mundane and the apolitical. It’s a reminder that life—with all of its comparatively frivolous existential crises—continues to happen to even the most competent among us. Between the moments in which the world is falling apart, and those in which we try to save it, the story goes on.

And a number of very interesting people seem to agree. A cast of megawatt stars—including Gloria Steinem, Meryl Streep, Judith Light, Lena Dunham and Martha Stewart—has volunteered to read for the audiobook. Still, despite all the love coming her way, Nevins says we shouldn’t expect another biographical tome from her anytime soon.

“I’ll be selling bras in Bloomingdale’s before I do this again,” she declares. And then, conspiratorially: “I’ll tell you one story. When I was a little girl and I got a good grade in elementary school, my mother used to say, ‘You know, your grandpa used to sell socks in a pushcart on Orchard Street.’ Then I went to the High School of Performing Arts and my mother said ‘Look, you got into the School of Performing Arts; your grandpa used to sell socks on Orchard Street.’ Then I got into Barnard and my mother said ‘Look, you got into Barnard; your grandpa used to sell socks on Orchard Street.’”

As Nevins speaks, the comforting rhythm of her story takes on the shape of a folktale or a joke told just before someone pulls a quarter from behind your ear. You wait for the punch line.

“Then I got into Yale, and my mother said, ‘Your grandpa used to sell socks on Orchard Street!’” She pauses for effect. “Well, you know what, now I’m selling books on Orchard Street. I’ve come back full circle to my immigrant origins.”

That may be, but Nevins has never told tales for the sake of the sell. She knows the best stories are the ones no one knew they needed—but once they’ve been heard, it’s impossible to imagine the world without them.

Portrait by: Brigitte Lacombe