A new biography of media tycoon Robert Maxwell, Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain’s Most Notorious Media Baron (Harper) by John Preston, documents a life riddled with ups and downs. These days, he’s more famous for being the father of Ghislaine Maxwell, who has been charged and is currently imprisoned over her role in the sexual exploitation and abuse of multiple minor girls by Jeffrey Epstein. When Robert Maxwell died in 1991 while out on his boat, the Lady Ghislaine, in the Canary Islands, the official cause of death was a heart attack (he was presumed to have fallen off his yacht)—but the circumstances were highly suspicious. The newspaper baron, who was facing financial ruin at the time, once represented power and wealth. Here’s a snapshot of his arrival into New York media society in the early 1990s upon buying the New York Daily News newspaper.

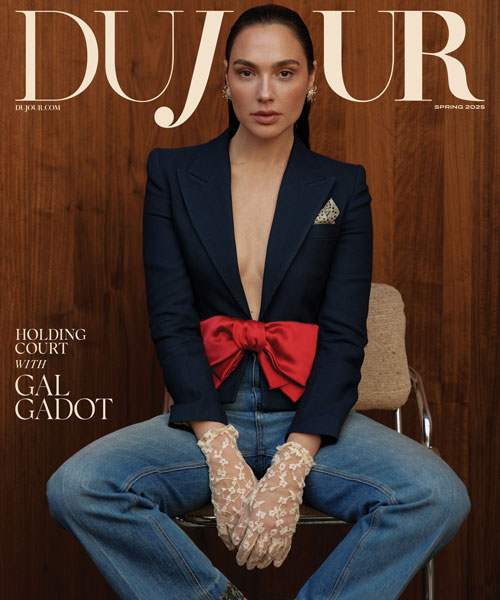

Robert Maxwell on his private jet

Just as its owner had intended, the yacht that made its way slowly up Manhattan’s East River and docked at the Water Club at East 30th Street in early March 1991 caused a considerable stir. For a start, it was far bigger than any of its neighbours—so big that it took up eight berths instead of the customary one. Four storeys high, gleaming white and topped with a mast bristling with satellite equipment, the yacht could clearly be seen from several blocks away. The man’s identity and the reason for his visit soon became the subject of much excited speculation. In several newspapers it even displaced reports of the end of the first Gulf War from the front pages. Who was this “portly press baron with the bushy eyebrows, the square jaw and the sly smile,” people wondered. What little was known about him piqued their curiosity even more. Born to a peasant family in Czechoslovakia, he had apparently fought for the British Army during the War and been awarded one of the country’s highest medals for gallantry. Now he was understood to be the possessor of a vast mansion, as well as a “40-button portable telephone.” He was also described as “a symbol of an Age of Flash. Of big-time dreams and big-time deals.” It seemed that his private life had been scarred by terrible tragedy and his business career by controversy. As for his personal fortune, this was estimated at between a billion and two billion dollars—a figure that was confidently predicted to increase by as much as $500,000 by the end of the year. Among the many publications he owned was the Daily Mirror, the biggest selling left-wing tabloid newspaper in the U.K. This alone gave him enormous political influence.

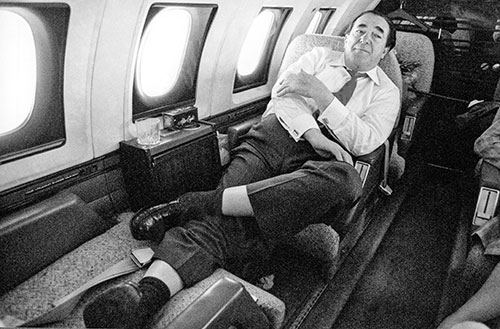

Robert Maxwell with colleagues Andrea Martin and Peter Jay

According to Bob Bagdikian, dean of the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, “Neither Caesar nor Franklin Roosevelt nor any Pope has commanded as much power to shape the information on which so many people depend.” New Yorkers would have to wait several more days before they caught their first sight of the yacht’s owner. But once seen, he was not easily forgotten. At nine in the morning on 13 March, a convoy of stretch limousines drew up beside a news stand on 42nd Street. Out of the first limousine stepped an extremely large man dressed in a camel hair coat and a red bow-tie, with a green-and-white-striped cap perched on top of his head. Showing unexpected nimbleness for someone of his size, he sprang up onto the sidewalk. A crowd of around 300 had gathered to witness his arrival, along with several TV crews. “Good on you!” one of the onlookers shouted. Another one called for three cheers. As the hurrahs rang out, the man grinned in delight and took off his cap to reveal a head full of startlingly black hair. He twirled the cap in the air, before holding up his other hand for silence. The cheers died away. “This is a great day,” he announced in his booming treacly voice. “A great day for me, but above all for New York. It’s the first good thing that New Yorkers have seen happen in a long while. The city has lost confidence in itself. People are departing. I say enough! New York still has something to say. The fact that I have chosen New York is a vote of tremendous confidence in this city.” Then, holding both arms above his head now, his fists clenched in triumph, he went even further. “It is a miracle!” he said, “A Miracle on 42nd Street!” At this point he was approached by two policemen, who asked if he would mind moving on. The problem, they explained with uncharacteristic deference, was that so many people had come to see him they were spilling out into the road; as a result, lengthy tailbacks were stretching in both directions. Of course, said the man; the last thing he wanted to do was to cause any inconvenience. Rather than get back into his limousine, he strode away up 42nd Street, his camel hair coat trailing out behind.

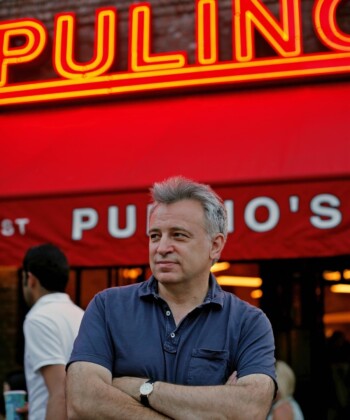

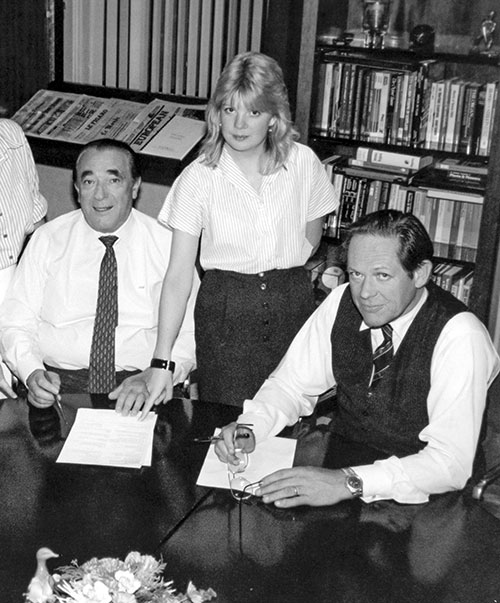

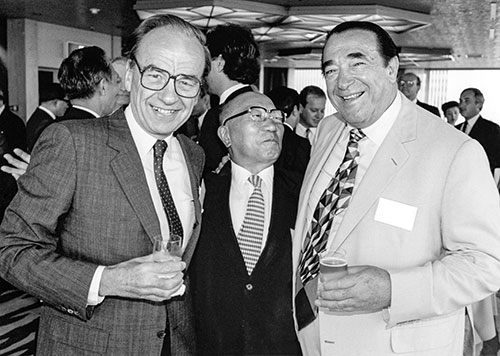

Robert Maxwell, Yosaji Kobayashi and Rupert Murdoch

Far from dispersing, the crowd and the TV crews set off in pursuit, loath to let him out of their sight. The man’s name was Robert Maxwell, and this was the day that all his dreams had finally come true. As he often liked to say later, Maxwell had come to New York in answer to a plea. A saviour was needed in the city’s hour of need and Bob the Max, as he’d taken to styling himself, was not about to shirk his duty. This was not strictly true—indeed, it wasn’t really true at all—but amid the excitement no one was in any mood to get too hung up on detail. Eighteen months earlier, in the autumn of 1989, journalists on newspapers in Orlando, Newport, Rhode Island, and Fort Lauderdale were surprised to receive letters asking if they would like to come and work in New York for a while. Anyone who expressed interest was then sent—in strict confidence—a list of instructions on what not to do if they decided to take up the offer:

■ Don’t stop to talk to anyone who approaches you.

■ Don’t frequent restaurants in close proximity to the office.

■ Don’t make eye-contact with passers-by.

At the same time, Jim Hoge, publisher of the New York Daily News, launched the first salvo in what he strongly suspected would be a fight to the death. The New York Daily News was the oldest and most iconic tabloid newspaper in America. In its heyday, it had sold 2.4 million copies a day—more than a quarter of the city’s population. Brash, blue-collar and fiercely proud of the breadth and depth of its prejudices, the paper liked to style itself “The Honest Voice of New York,” a claim rather belied by the fact that it also ran a regular “Gang Land” column—a kind of low-life social diary chronicling the ups and downs of the city’s best known organized crime figures, such as Vincent “Chin” Gigante and Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso. But the News’s heyday had long gone. For years, it had been hobbled by astounding levels of over-manning, widespread corruption, an exorbitant wage bill and machinery so antiquated that printers were reputed to have to blow black ink out of their nostrils for several hours after their shifts had ended. By 1989, it was losing $2,000,000 a month. In a bid to break the unions’ power, Hoge decided to take them on. He planned his campaign with meticulous precision. If they went on strike, as he was convinced they would, he intended to keep the News running with non-union labour—hence his appeal to out-of-town journalists to come to New York. In a former Sears warehouse in New Jersey, he even built a full-scale replica of the paper’s newsroom so that people could be properly trained beforehand. The warehouse was surrounded by a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire and patrolled round the clock by security guards with German shepherd dogs. The choice was stark, Hoge told the unions. Either they had to accept new machinery and a dramatically reduced workforce, or else the paper was doomed. To no one’s surprise, negotiations swiftly broke down.