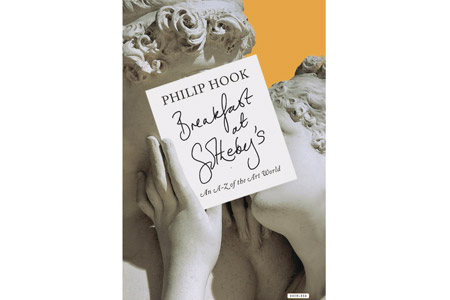

Philip Hook has spent more than three decades honing his innate knowledge of the art world. The London-based art expert and author began his career with Christie’s in 1973 before landing at Sotheby’s 20 years later, where he currently serves as a board member and the company’s senior director of Impressionist & Modern art. In his book Breakfast at Sotheby’s (which was just released to the U.S. market), Hook provides a light-hearted and entertaining view of the prim and proper world of high-valued art, mixed with witty anecdotes from his career.

Breakfast at Sotheby’s

Here, the art aficionado offers the ten critical touch points he uses in establishing the value of a painting.

1. Authenticity

Confirming the authenticity of a work is a given, but it’s not always black and white. “There’s a sort of speculative authenticity that can put up a value of a picture. You can have pictures that might possibly be by Rembrandt, but probably aren’t, but because they might possibly be by him, they get a little extra speculative value to them.”

2. Famous Artists

A big name is equivalent to high price. Hook says that figures like Rembrandt, Leonardo, Titian, Picasso and Matisse will always maintain their value.

3. Artists in Vogue

Certain artists will never go out of style, but other movements tend to vacillate in the market. “While the highest prices a generation ago were made by Old Masters, now they’re made by contemporary artists, so there’s been a shift in taste that depends on the generation buying it.”

4. Positive Romantic Baggage

Hook uses this term to describe an artist who has a romantic and dramatic backstory. “Madness is good news commercially because it takes part in the inspired madness of creativity,” explains Hook. On the other hand, he says, illness is seen as a negative. “Buyers feel that if the artist was ill when painting a picture, it’s probably not going to be very good.” Dying young and suicide also bump up prices—they’re factors that limit the production of the artist’s work, making pieces increasingly rare.

5. Career Peaks

When an artist produces particularly strong work during a certain time period, that time period holds a high value. Hook gives the example of Picasso, whose paintings in the 1930s are priced significantly higher than works from later in his career.

6. Typicality

“It’s not so much the quality of the painting, but whether it is a typical or easily recognizable one to the artist.” In the case of Monet, Hook reminds us that water lilies almost guarantee a reaction of, ‘“My God, you’ve got a Monet!’”

7. Subject Matter

Although subject matter is one of the biggest and most diverse factors in valuing art, Hook suggests a few simple guiding principals. “Happy pictures are better than unhappy pictures. Sunny landscapes are better than bad weather,” he says. “And pretty girls are worth tremendously more than portraits of ugly old men, even by the same artist.”

8. Condition

A painting in quality condition always increases its price—an assessment that requires an expert eye. Often, older damaged works are laser repainted by another hand, which causes a decrease in value.

9. Provenance

The history of a picture’s ownership can have a big affect on its value. For example, a piece that was confirmed as being stolen by Nazis during Nazi Germany would be considered a downer for an art collector.

10. Wall Power

What Hook calls “Wall Power,” or the sheer quality of the work, always factors into a painting’s price. “The sort of impact it makes on you as a piece of work, from composition, color, and size,” he says, all affect the amount a person is willing to spend on it.